Tuesday, 26 February 2013

MOTŐRHEAD: No Sleep ‘Til Hammersmith

(#246: 27 June 1981, 1 week)

Track listing: Ace Of Spades/Stay Clean/Metropolis/The Hammer/Iron Horse/No Class/Overkill/(We Are) The Road Crew/Capricorn/Bomber/Motörhead

The only thing that could logically have followed, and rebutted, Stars On 45, would have been an album filled with unrelenting noise. But unrelieved noise without context or point can be as conservative as Randy Crawford or Richard Clayderman; you know exactly what you’re going to get, there is no room to discover anything else, it is as absolute as James Last (to call up that other Star Sound analogy or ancestor you thought I’d forgotten about).

Luckily Motörhead don’t do “noise” as such, even if they are usually noisy, even if Peter Brötzmann (that umlaut is the giveaway) and Sonny Sharrock could stand alongside them and not sound remotely out of place (1986’s Orgasmatron is the comedy side of that year’s Laswell/Hardcore Motherfucker trilogy of records, alongside the first Last Exit LP and Public Image Ltd’s Album). Nor are they especially Hard Rock or even Heavy Metal as such; if anything, this live LP, the first contemporary one to crop up in this tale since Stupidity, proves again and again just how light their metal was, even though there are only three musicians to cover all the bases and holes; Philthy Animal Taylor is a remarkably busy and forceful drummer, but in the Ronald Shannon Jackson/Phil Seamen sense – he can seem serene as spring even when offloading the endless fusillades on “Overkill.”

Neither, thank the Lord, do they do “concepts” or “profundity” – although I note, on “(We Are) The Road Crew” and especially “Capricorn,” how close they can get to Cream or even Hendrix. No, Lemmy sees Motörhead as rock ‘n’ roll, just as Gene Vincent or Eddie Cochran would have known and felt it, and the trio’s music, despite its surface thickness, dispenses with all the clogging up that rock had endured in twenty years of respectability; it offers nothing but rock, and the infinite possibilities that lurk within it.

Despite the title, the album was actually recorded largely in Leeds and Newcastle – indeed, you can hear the Newcastle audience being named and worked up in the prelude to “Road Crew” – in early 1981 (as part of a tour that reached West Runton Pavilion but not Hammersmith Odeon as such), with “Iron Horse” being pulled from a 1980 performance. It is relatively brief (or feels as such) and completely glorious, and I recall in 1981 student record collections how it could be filed next to Kilimanjaro and Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret without looking at all out of place.

There are other Motörhead records you should have – 1984’s double career retrospective No Remorse, for example, has no less than eight tracks from No Sleep, together with the indispensable and definitive “Killed By Death” – but if you’re only going to go for one, then this is the one to go for. There is little point indulging in long-form lyrical analysis, since that is never what Motörhead has primarily been about, but words and lines do pop out of the general picture, like a…well, like a punctum; “Win some, lose some, it’s all the same to me,” “I don’t wanna live forever” (both from “Ace Of Spades”), “We shoot to kill/We always will” (from “Bomber”), “Don’t know how long I’ve been awake” and the use of the word “parallelogram” with only Linda Perhacs as an unlikely precedent (both from their titular theme song). Basically it’s about drinking, smoking, gambling, being on the road, rocking and warplanes and other general Boy’s Own matters. “Capricorn,” Lemmy’s idea of “a slow one, so you can all mellow down,” is faster than anything Red House Painters have ever recorded and could give 1987 Marshall Jefferson a run for his money.

But it is not the one song repeated eleven times. There is absolutely no fat; Fast Eddie Clarke concentrates on being fast and unshowy – frequently Lemmy’s fuzz bass is obliged to cover the chords – and I am reminded, of all unlikely comparisons, of Creedence; the same cast-iron certainty and absence of side about what they’re doing and how they’re doing it. “Stay Clean” and “Iron Horse,” if anything, shuffle. “No Class” leaps out of its box and grabs your throat as assuredly as Vincent’s “Dance To The Bop” did all those years before. The multiple pile-ups and false endings on “Overkill” are thrilling and apposite – oh, come on, one more once! “Capricorn” itself makes me think of one road the Stooges could have taken after Kill City. The road crew themselves ham furiously but playfully in the spoken intro to “Road Crew.”

And the climactic “Motörhead,” a #6 single on 45 release (backed by a hearty “Over The Top,” not on the original album but present on the CD edition), is an all-inclusive apocalypse. The listener is struck by just how welcoming an umbrella theirs is, as minimalist and severe as it may initially appear; there are no dumb Coverdale rump-thrusts – indeed, in the multiple Polaroids which decorate the inner sleeve there are several of the female hard rock band Girlschool hanging out with the ‘Heads. But “Motörhead,” the song, is extreme only in the sense of the neutered stuff that hung around it; as Clarke gives out some Scotty Moore licks at the climax of his solos, the listener is reminded that THIS is what the golden years of rock ‘n’ roll were all about, rather than milkshakes and wine; as the song excitingly and steadily builds up to its detonating climax, it does not feel that Motörhead are trashing rock as such, but reviving it; the ending is one of the most drastic and unanswerable on any number one album since “A Day In The Life,” complete with the solitary feedback tone at the end – what could follow that? Only an actual bomber ‘plane, complete with air-raid sirens echoing the audience’s football chants and booming claps.

Not “macho” or “serious” but definitively great at what they do, enough that the Beastie Boys would be moved to name a song after the album’s title, enough to bestir an eleven-year-old Dave Grohl – if we’re talking about uncompromising power trios to come – Motörhead, the least pretentious but most intelligent of all rock bands, remind us why we left our parents’ past in the first place. Elvis should have lived to work with these guys; what is “Iron Horse,” after all, if not an updated and beatified “Mystery Train” for its refreshed times?

Next: a new marketing innovation, and another unwittingly important piece of the New Pop jigsaw puzzle.

Sunday, 24 February 2013

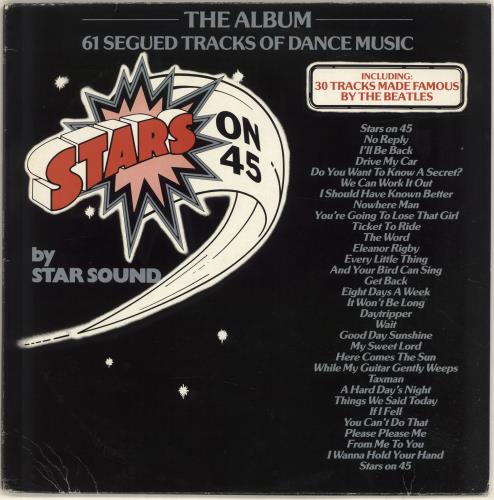

STAR SOUND: Stars On 45

(#245: 23 May 1981, 5 weeks)

Track listing: Stars On 45/No Reply/I’ll Be Back/Drive My Car/Do You Want To Know A Secret/We Can Work It Out/I Should Have Known Better/Nowhere Man/You’re Going To Lose That Girl/Ticket To Ride/The Word/Eleanor Rigby/Every Little Thing/And Your Bird Can Sing/Get Back/Eight Days A Week/It Won’t Be Long/Daytripper/Wait/Good Day Sunshine/My Sweet Lord/Here Comes The Sun/While My Guitar Gently Weeps/Taxman/A Hard Day’s Night/Things We Said Today/If I Fell/You Can’t Do That/Please Please Me/From Me To You/I Want To Hold Your Hand/Stars On 45 (Medley) (Star Sound)/Stars On 45/Boogie Nights/Funky Town/Video Killed The Radio Star/Venus/Sugar Sugar/Cathy’s Clown/Breaking Up Is Hard To Do/Only The Lonely (Know The Way I Feel)/Lady Bump/Jimmy Mack/Here Comes That Rainy Day Feeling Again/Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini/Stars On 45 (Medley) (Star Sound)/Do You Remember/Lucille/Bird Dog/Runaway/Bread And Butter/That’s All Right [Mama]/Rip It Up/Jenny Jenny (Medley) (Long Tall Ernie and The Shakers)/Golden Years Of Rock And Roll/Sherry/Wooly Bully/Buona Sera/Slippin’ And Slidin’/Nutrocker/At The Hop (Medley) (Long Tall Ernie and The Shakers)

Look, I’m not trying to be John Ruskin here and insist on unshakable aesthetic absolutes. But nor am I being an uncritical leveller, trying to paint a picture where every number one album is exactly as good, or as bad, as every other number one album – much as one might wish in an ideal world. The key word on the tagline at the top of this page is “might”; I’m not for one moment suggesting that anybody would want to listen to every one of these records, simply that many deserve some form of reconsideration and re-addressing.

This doesn’t just mean that some number one albums are “better” than others but also that some number one albums stink to low hell. And that’s not just a standard objective versus subjective internal brain-tearer. I recognised the inaudible collective sigh of relief when this blog got to Please Please Me after some eight months of what many considered tedious preliminaries, a list of records which might still adorn the average Sunday playlist on BBC Radio 2, an unceasing cycle of Hollywood musicals, Elvis, Frank, Cliff, Shadows…and three albums by the George Mitchell Minstrels, which I’d be surprised if anybody played any more (I recall one comment on an early Bob Dylan entry which expressed relief that we were past all those “minstrel abominations”) with their interminable singalong/clapalong medleys of tunes which might once have been good.

The point is that when the Beatles came along, the George Mitchell Minstrels were part of what they had come to overthrow, the stultifying non-culture, the refusal to allow teenagers to be anything other than miniature replicas of their parents, the continuing, unquestioning, suffocating cap-in-hand deference to an unspecified, but presumably superior, past. They represented a fresh start, an end to all the compromise that had been settled for before they came.

So you may understand my residual dismay at how, a generation later, and with one of the Beatles recently dead, this record felt as though the George Mitchell Minstrels were circling around the corpse and reclaiming it as one of their own, all along. Side one of Stars On 45 is a gruelling listening experience, with its implicit suggestion that, really, “The Beatles” never happened.

The concept had its accidental generation in Montreal, where a studio group under the name of Passion put together a bootleg mix of various songs and snatches, including “Sugar Sugar” and “Venus” as well as a four-minute segment of Beatles songs, sampling the original recordings (there had been in 1977 a single called “Disco Beatlemania,” a sequenced medley by another studio group calling itself DBM, but this has no apparent relation to Star Sound). One Willem van Kooten, the head of the Dutch music publishing firm Red Bullet Productions, heard the record in a shop one day. He was impressed by it but realised from the unauthorised use of “Venus” – to which Red Bullet held the copyright – that it was probably illicit. He contacted Jaap Eggermont, the somersaulting ex-drummer of Golden Earring, who commissioned a group of session players and singers to go into the studio and record two long soundalike medleys, incorporating the elements from the Passion disc (which was entitled “Let’s Do It In The ‘70s – Great Hits”) and avoiding any undue legal calumny – although the “Stars On 45” theme itself borrows heftily from Sparks’ “Beat The Clock” and the SOS Band’s “Take Your Time (Do It Right)” without crediting either.

The initial single took off immediately and a slapdash album, which in various parts of the world had different titles, different covers, different track listings and even different artist names, was assembled. The single version closely followed the Passion original; the album mix funnels out the Archies and Shocking Blue elements and concentrates on the Beatles for fully sixteen minutes.

And it is vile. Not so much as a wake of mourning at Lennon as outright necrophilia. I have heard the Passion original, and the cutting and pasting, using original sources, is skilful and clever. In addition, the selection of Beatles songs used is far from obvious. But Star Sound dismisses all this in favour of gloomy Dutch voices doing their best to sound like John (reasonable), Paul (not too good) or George (dismal; see “Here Comes The Sun” for an especially gruesome example). At no point do you not think that you are listening to anything other than a smudged Xerox of something that was once great, crucial even; all the art, from “Taxman” to “You Can’t Do That,” traduced to a cold procession of cheap-sounding “best bits” (and the interjections of “Eleanor Rigby” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” into the unchanging boom-CLAP-boom-CLAP rhythm track are as painfully ungainly as you’d imagine). It is like putting an enlarged cardboard cutout of John Lennon at the dinner table and pretending he’s the guest of honour.

The medley suggests, in a longer-term setting, that the Beatles amounted to nothing but an assortment of cute bits which can be easily chopped up and set to a “dance music” beat. At least Frank Farian’s Boney M had some semblance of personality with their absurd cover versions, even if it was usually Frank Farian’s. But who is this Star Sound? And who cared? This isn’t even the knowing anonymity of the Top Of The Pops records, with session singers making the best of a bad job, but dead-handed nothingness. Listen to it from three rooms away and it might vaguely sound like the Beatles. Listen to it close up and it sounds like pop gruel. The stupid theme comes back at the end, hangs around and then slowly fades, as if it’s going to live forever. Nothing is changed, no one is really moved.

And I’m not necessarily looking for “depth” in these albums – not all the time, anyway – but just some evidence that life and thought have been put into them. Side two is so awful it almost makes side one sound like Echo and the Bunnymen’s Heaven Up Here - a record from the same period and a far more fitting tribute to Lennon, in its own across the Liverpudlian universe way. The other “Star Sound” medley plays as if someone cut up a list of hit records and pulled them randomly out of a hat. A mash-up of “Boogie Nights” and “Funky Town” is attempted. The rest is unlistenable; “Cathy’s Clown” glued over boom-CLAP-boom-CLAP is so inept I could have done it. Not fun, not camp, not ironic – God forbid – and not even that disco. Who would be dancing to this?

Long Tall Ernie and the Shakers? Viewers of the recent 1978 TOTP repeats may shudder at the name, and with good reason; they were on doing the “Do You Remember” segment of this record (yes, it was also produced by Eggermont, hence its pad-out-the-album reappearance here) and if rock and roll ever had anything to do with anything, there’s no evidence of it here. The “Little Richard” sounds like the “Paul McCartney” on the other side. Elvis? Didn’t he mean something…once?

“Golden Years Of Rock And Roll” is, however, worse, if that is possible; lyrics which sound constructed using primitive BabelFish (“Had a good time/Milkshakes and wine” – WHAT?) with impressions of Holly, Presley and even Paul Anka (“I’m so young and you’re so old/Another record that went gold” – readers, I kid you not) so bad I’m convinced they were deliberately so, as if to undermine and even ridicule what these people might once have meant. Buddy? Ah-well ah-well isn’t it time for Blankety Blank? Here, Sam the Sham and Louis Prima (though “Buona Sera” sounds here as though “sung” by Gibby Haynes of the Butthole Surfers) are put through the same lowest common denominator coffee grinder, stamped out of individuality and even existence. “At The Hop” is sung like Elvis and the singer vomits halfway through. The end of the record can’t come soon enough.

And yet FIVE weeks at number one. WHY? This raises in my mind questions that I maybe don’t even want to think about. No self-respecting disco, mobile or otherwise, would have played this. Who was it for? Get your mates in, push back the sofas, roll up the carpet, open up the Watney’s and aWA-HEY you go? I mean, it goes beyond even the point of people wanting songs rather than singers as such. The soundalike albums we’ve done before may have been cynical to a point but at least they gave you whole, unbroken songs.

But this…well, the copy I bought still has its blue, yellow and white “BLITZ PRICE £3.99” sticker on it – and I paid substantially less than £3.99 for it – which I seem to remember was from Our Price, or was it Virgin, or who knows (it’s so long ago it’s fled my memory)? All I know is that you could have bought anything else for that price, or cheaper, at the time; not just Heaven Up Here but Computer World, or Flowers Of Romance, or even Mutant Disco - a dance record that truly is everything that Stars On 45 isn’t, and one I still play for pleasure to this day. Or Nightclubbing.

But no, people wanted to grasp on to…I don’t know what. Not a memory, probably not even much to do with John Lennon or the Beatles. Just…people who don’t only buy only ten albums a year, but probably don’t like music that much. It has a beat of some sort, and apparently that is enough. And unlike everywhere else in the world, where Stars On 45 was treated as a charming little novelty before humanity moved on, Britain was plagued by a veritable St Vitus’ Dance epidemic of copyists and ambulance chasers, such that by July or August of 1981 the singles chart was in danger of being choked by the multiplicity of crappy dance medleys dominating it. Then “Tainted Love” went to number one, and the picture changed again, and for the better, and the medley craze slowly slithered out of sight and out of the charts. It is as if Britain had been gripped by a temporary madness of mass delusion.

Still, it is unsettling, and to me something of an insult; you spend a year with number one albums, building up and up in quality and importance, and suddenly you are thrust back down to the dregs. As I said, 1981 was a year of violent extremes of reaction; the two record-shopping tribes now perhaps gone to war. But if that had only been the end of it, instead of which, as the eighties jog to an end, up pop Jive Bunny and the Mastermixers to thrust us back into the Bronze Age once again – and maybe Stars On 45 was a first and fateful step to the current state of atrophy where people no longer seem to want songs, with beginnings, middles, endings and points, but 30-second segments of songs (“Harlem Shake” is 30 seconds of mediocre imagination left to run for three-and-a-half minutes). Where listeners no longer wish to listen, or even to work, at music; it’s all there, carefully filleted for their instant gratification. There is just no life here, least of all John Lennon’s.

I have no hesitation in naming Stars On 45 the worst album I have so far listened to as part of this exercise. And it’s not as though there isn’t worse to come (unbelievably, there is). But if Adam and the Ants – on the same label as Star Sound, never let it be forgotten – offered “Antmusic,” then Star Sound offer “ANTI-music.” One listens to this record and wonders if the people behind it actually hate music. It would certainly persuade the undecided listener never to bother with music again.

Oh, and Jaap Eggermont didn’t remember “Twist And Shout” since it’s not included. I have no doubt that the shade of Bert Berns was enormously grateful.

Next: every action has an equal and opposite reaction – the worst number one album is displaced by one of the most extreme number one albums.

Friday, 22 February 2013

Phil COLLINS: Face Value

(#244: 21 February 1981, 3 weeks)

Track listing: In The Air Tonight/This Must Be Love/Behind The Lines/The Roof Is Leaking/Droned/Hand In Hand/I Missed Again/You Know What I Mean/Thunder And Lightning/I’m Not Moving/If Leaving Me Is Easy/Tomorrow Never Knows

When I wrote about Duke I mentioned that Collins was going to be this decade’s Rod Stewart, in that he is going to be present right through it and his artistic trajectory moves in a not dissimilar fashion. In the eighties alone he appears three times on his own, four times with Genesis and on any number of compilations in either capacity. He is Then Play Long’s top eighties rep reliable.

This being the case, Face Value, his solo debut, must count as his Every Picture Tells A Story; it is his best and most adventurous record and conveys the feeling of being put together for tuppence. Then again, that’s only a feeling; the gatefold inner sleeve may picture a desktop filled with workaday paraphernalia – track credits appearing as Post-It notes, numerous snapshots, including one of his two children, scribbled and crossed out rough notes that look like TPL drafts – but most of the pictures are of him hanging out in LA with or without his co-producer Hugh Padgham, and some are of his musical mates. If you’re able to hire Eric Clapton or the Earth, Wind and Fire horns then it’s presumed that Face Value, half recorded in LA and half in Goldhawk Road – the latter not far from Chiswick, where he grew up – cost rather more than tuppence to make.

Still, the album received excellent reviews at the time, and can best be viewed, as was part of the original impression, as a sort of magazine; flick through its pages and read features on widely differing subjects. Taking Fripp’s Exposure - on some of which Collins played – as a template, Face Value is laid out as a politely eclectic showreel; here, its author seems to say, is what I’m capable of doing outside Genesis, here’s what I have to offer.

The album was actually put together over a period of some eighteen months, beginning in late 1979. Collins had gone through divorce with his first wife and the moods this engendered are pretty evident on most of the record, though not all of it; the exacting slo-mo torture of “You Know What I Mean” and “If Leaving Me Is Easy” is offset by brighter portraits – inspired by his new partner – in “This Must Be Love” and “Thunder And Lightning.” There is no real attempt, as such, to tell a story; the aim is…well, that’s a good question.

In his 1982 NME interview with a sceptical Morley – reproduced in Ask: The Chatter Of Pop - Collins is eager to emphasise that he is not merely “commercial” or “trite” but is far too cagey yet at the same time too quick to jump to defend perceived attacks on his music and character. Thus no common ground is found, and a lot of mutual frustration is left in its place. He struggles to explain exactly what his audience would find so attractive and compelling about his music, but I think he might have been aiming at something like this: Face Value, although no one in 1981 knows it, will help define the sound, texture and gestures of what we might call the rest of the decade’s “hip MoR,” or “technologically advanced AoR” if that’s a little less ambiguous. It is a record of its time, yet made by and for people whose time stretches back beyond the eighties, possibly even back towards the sixties; those who believed, somewhere, that something was going to change, and when it didn’t, blamed themselves, and grew to hate the new stuff that came up and appeared to sneer at what they had believed and possibly still believed, and so needed something that sounded new but was also hugely reliable.

Likewise, the record’s main subject matter is quite unambiguously an adult one, a theme designed to be understood by adults of a certain age who had gone through something similar and could empathise with it. This was music for people who had, more or less, “grown up” with Collins’ music and now needed music that echoed the way they felt, given that their lives hadn’t perhaps turned out to be as good as they thought they would do back in 1968 or 1975.

It was a masterstroke to commence the album with its most extreme piece of music, and also have it be the album’s lead (and biggest-selling) single. As the 45 of “In The Air Tonight” peaked at #2 in Britain, I will again leave a more in-depth analysis of the record to Lena; suffice it to say that in the context of its album, it immediately sets an overall gloomy and suspicious tone, shows how well and how much Collins had learned from working with both drum programs and drumkit on Peter Gabriel 3 and is probably the best white soul lament masquerading as obfuscatory art-rock since “Whiter Shade Of Pale.” On Twitter, Rizzle Kicks recently compared the sudden drum onslaught midsong – still a shock, if you’ve never heard it before – to him coming downstairs in the morning (I thought of the equally startling drum avalanche that resuscitates the Raspberries’ “Overnite Sensation (Hit Record)”). Credit must also be given to the expressive guitar of Daryl Steurmer and, buried almost subliminally in the mix, L Shankar’s violins, as well as to Collins’ own drumming; on this song alone you can hear how and why he would appeal to hip-hop heads, from Ice-T downwards – not only are his beats big, but they are also non-obvious; on the album there is virtually no straight 4/4 playing – Collins listens and plays like a jazz drummer, always subdividing the rhythm or carefully playing away from the centre.

“This Must Be Love” is relatively upbeat, and yes, may sound like Steve Winwood beer commercials in years to come – but in 1981, this sound was not yet a cliché, was in many ways rather new. Nonetheless, I’m sure that the song’s cautious optimism wouldn’t have worked so well if it hadn’t been for Collins’ close collaboration with John Martyn on the latter’s Grace And Danger album in 1980; another record chiefly inspired by a messy and painful divorce – songs like “Some People Are Crazy” and “Hurt In Your Heart” make explicit what Face Value only, for the most part, implies – and there’s more than a touch of the Martyns about Collins’ own vocal (despite breezy back-up singing from Stephen Bishop, of “On And On” fame); witness the gulped, caught in his throat, “I’d” in the line “Happiness is something I thought I’d never feel again.”

“Behind The Lines” reappears, overhauled and completely reworked, from Duke, and the EWF horns and Alphonso Johnson’s bass help Collins achieve a certain swing that the original doesn’t quite reach, hence bringing out the song’s underlying exasperation more effectively. But “The Roof Is Leaking” is remarkable, this record’s “Mandolin Wind.” It’s winter, he’s stuck in a freezing house with cold kids; somebody else, “Our Mary,” has gone off with “her young man” to “the coast” (if they ever made it there), and “my wife’s expecting.” This house has been in the family forever, and the protagonist is dimly aware that they may die in it, but its windy emptiness puts me in mind of a fusion of the two manifestations of young misery of Dell Parsons in Richard Ford’s Canada; lonely in Great Falls, Montana, with a family that is about to pull itself apart – and with a twin sister who will go off with her young man to the coast – and lonely again in some godforsaken backwater of a no-horse town in Saskatchewan, freezing in his unwelcoming, unlit shack, still avoiding death. The song is dominated by Collins’ dour piano, although the middle eight perks up a little (“I’m getting stronger by the minute”) with the addition of Steurmer’s banjo and Jo Partridge’s slide guitar before being placed back into misery. Collins’ “But spring will soon be here” is met by a sudden stop, followed by a fear-filled whisper of “Oh God, I hope it’s not too late.” Throughout the song, crickets chirp in the background.

Collins knows that this song cannot really be followed, and so the rest of side one is given over to two linked instrumentals which take us on a pleasant whirlwind tour of the world; there the bayou, here African percussion and chants, now some Eno ambience, a touch of Orientalism, the horns of EWF, and as a culmination of sorts, an assemblage of children from various church choirs in Los Angeles – Lena assures me that this part sounds VERY LA – joined by Collins’ bright marimbas. Soundtrack music? British Airways commercial? Possibly, but Collins does convey some element of catharsis and release – although the careful listener will note that “Hand In Hand” ends with the same drum program, and indeed the same key, as “In The Air Tonight.”

Side two kicks off with the terrific “I Missed Again,” far more Motown than EWF (we decided that from that perspective, it would have to be done by Jimmy Ruffin, he of the Detroit School of Hard Knocks), and the seamless fusion of “black and white” or post-prog and soul, that Collins has maybe been aiming for all along. Brian Case had the misfortune to review the single for Melody Maker and crossly attributed the tenor solo to “some Gato Barbieri disciple”; it was Ronnie Scott. But this is the record’s most driving and exciting – and genuinely angry – song.

After that comes the brief but shattering “You Know What I Mean,” with the Martyn Ford Orchestra strings and Arif Mardin’s arrangement, a sort of “I Will Survive” in reverse, she comes back (“Just when I’d learned to be lonely” he muses), and he’s too tired and hurt to deal with it, or her. But he quickly blasts himself out of his corner again with “Thunder And Lightning,” complete with two Maurice White impressions in the intro. Steurmer does the guitar solo; Collins maintains “I never did believe in guiding lights” but really can’t believe his luck.

In the next two songs, though, he’s just been left on his own again; “I’m Not Moving” plays like a chirpy US sitcom theme (though that “if it hurts, don’t do it” cuts, as it was surely meant to do) – go on then, he says, go if you’re going, I can’t boss you around. With its vocoder doubling-up of Collins’ lead vocal, the song could have dropped off the end of McCartney II.

But on “If Leaving Me Is Easy,” he has indeed been left on his own, had his bluff called, and although there is a touch of Smokey Robinson about the lyric’s central conceit (“Oh sure all my friends come round, but I’m in a crowd on my own”), there is now only emptiness, and memories, and crushing, squashing guilt. He knew it was coming to an end and perhaps still refuses to believe it – he sings the song in the puzzled but emptied tone of the recently abruptly bereaved – and meanwhile, behind him, everything is quiescent, or in stasis; Clapton turns up on guitar, though you’d never know it, while the two warm EWF flugelhorns conjure up the old “That’s The Way Of The World” feeling; but, although both songs share an alto sax solo by Don Myrick, this song is very different from “After The Love Has Gone” – it seems more…terminal, as Mardin’s strings hang suspended in space, the nothing that ensues in the deathly pause after Collins’ “Just remember” signoff. Multitracked, high-pitched Collins voices reappear for the final fadeout – is he trying to do the Bee Gees, and if so, why do the sudden tempo displacements and use of echo make him sound like the immediate ancestor of “Moments In Love,” not to mention the songs that Jam and Lewis will be inspired, in part by this, to write, whether “If You Were Here Tonight” or “Come Back To Me”?

And so the record ends with a cover of a song by…John Lennon.

It wasn’t deliberate; the album was planned long before 8 December 1980. Yet its placing and tone suggest a tribute – one of the most difficult of Lennon songs to pull off as a cover (the Chameleons had a game go at it on 1986’s Strange Times, and the Eno/Manzanera/Monkman re-reading on 801 Live is mandatory listening) – and Collins is canny by playing it, effectively, at half the speed of the original, so the whirling monastic dervish is succeeded by a patient meditation. The effects of the original are retained – the EWF horns lurch in and out of the picture, backwards and forwards, in a way that pre-empts Siouxsie and the Banshees’ “Peek-A-Boo” by over seven years – but they are like debris orbiting around a central satellite. And where exactly have we heard that beat before, recently? As the kids from LA rejoin Collins at the song’s climax – “Of the beginning, of the beginning” – it suddenly becomes clear, even more so than John Giblin’s bass in the introduction, which presages his own work with Simple Minds a few years later – that Collins is remaking the song as an ancestor to, and double of, “Biko.” If the theme of weather patterns which has permeated through the whole record has been sustained, then this “Tomorrow Never Knows” suggests that the storm has been passed through, that the sun will now shine again – a feeling underlined by Collins’ own final, hesitant rendition of the first verse of “Over The Rainbow.” It is a feeling of hope, and one day, in the not-too-distant future, Collins will work with both Adam Ant and one of Abba, but Face Value, in its shoulder-shrugging “well, this is what I do, what do you think?” persona, suggests that Collins was, at least in 1981, still greatly capable of doing quite a lot and getting somewhere. How he manages to get through the eighties may be an adventure in itself; but I remember saying something similar about Rod, and at such a time.

Next: you thought we’d finished with the George Mitchell Minstrels?

Wednesday, 20 February 2013

John LENNON and Yoko ONO: Double Fantasy

(#243: 7 February 1981, 2 weeks)

Track listing: (Just Like) Starting Over/Kiss Kiss Kiss/Cleanup Time/Give Me Something/I’m Losing You/I’m Moving On/Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)/Watching The Wheels/Yes I’m Your Angel/Woman/Beautiful Boys/Dear Yoko/Every Man Has A Woman Who Loves Him/Hard Times Are Over

It’s the image that does it.

There they are, on the front cover, a middle-aged couple in an embrace who look at least reasonably happy. One is maybe happier than the other, for only the man is kissing and has a visible arm around her neck. She is waiting to receive his kiss without giving any clear sign that it will be returned. But he appears glad, and the monochrome shot, which meant something different when the record came out to what it meant now, helped strike what I feel might have been the wrong chord. It’s him, isn’t it – but look how he looks now! Where’s the long hair, the glasses, the beard? Where are the seventies? His hair, if not exactly short, is – moptopped. He looks exactly like he did in 1965, that time when life was supposed to be better.

You see, John couldn’t even poke his nose above the trench without his history being brandished in his face.

Double Fantasy is one of the hardest of all number one albums to write about because it is now nearly impossible to imagine – did you catch that word, on the other side of the sky? – what it would have sounded like or how to write about it without the knowledge of what happened after it came out. It is virtually impossible to write about as an independent record of music.

But there is also the knowledge that without Mark David Chapman I almost certainly wouldn’t have been writing about this record at all. When it came out, in the mid-autumn of 1980, it did only respectable commercial business – in Britain it only peaked at #14, in the States #11 – and met with a frosty critical reception. It was late 1980, and the world was in trouble; who, the critical mean asked, wanted to listen to 45 or so minutes of a rich couple blandly declaring their love for each other, like a slightly hipper Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme, in a record packaged to resemble – the cover of A Star Is Born? Or incomplete memories of Rubber Soul?

In essence, John and Yoko (though mostly John) were decried for not being Paul Weller, whose group had at the same time released a scarily relevant record of angry and discursive songs (Sound Affects). The meagre pleasure available to the mourning reader after 8 December was to observe music journalists turning acrobatic cartwheels with their typewriters to change their opinions around completely (in the case of Melody Maker, the same writer). Oh John, boring us to tears again with your homespun homilies, converted rapidly to Oh John, why couldn’t he have been left alone to get on with his homespun homilies; here you can see a glimpse, perhaps, of why Chapman did what he did.

You can turn over the newest of leaves, the residual lesson was after the shooting, but no one will ever let you be; you will forever be encapsulated, or entombed, in that monochrome image, resuscitating memories of what and who once was. If you’re someone like Chapman, the image and the person get so hopelessly mixed up in your mind that you think you can snuff out an image and not hurt the person.

Yes, he probably should have headed back to Britain when punk happened, got his feet dirty, brought up Sean in Ladbroke Grove – or, at the very least, Chelsea – and yes he was beyond naïve to think that he, John fucking Lennon of all people, could happily stroll around the very dangerous place that was late seventies/early eighties New York without any threat, least of all from a psychotic Salinger misreader allowed by the Second Amendment to wander freely around the USA with a gun. But there is a brief comment from John and Yoko on the back cover of Double Fantasy which says: “With special thanks to all the people, known and unknown, who helped us stay in America, without whom this album would not have been made.” So staying in America was an active choice, and bringing up young Sean may have been the deciding factor.

In the 2000 CD edition of the record there are many photographs of the pair hanging out in and around New York; they could from a distance be any fortysomething holidaymakers. But what cannot – and clearly could not – be erased from people’s mindsets was that one of these people was once a Beatle, and everything that had once promised. Think of the all-night camps and sing-alongs outside the Dakota after it had happened, the grief-stricken pages of Rolling Stone and other such publications, the feeling on the part of many that something in their lives – and perhaps even their lives – had come to a full stop, and wonder what the Lennon who only a few months before recorded a cheerful, punky send-up of Dylan’s “Gotta Serve Somebody” would have made of it. Even in death, they could not let him rest in peace.

So Double Fantasy - the title comes from a type of freesia that Lennon had seen in the Bermuda Botanical Gardens; he had journeyed by boat from Newport (the Rhode Island/High Society one) to Bermuda earlier in 1980, ran into difficulties and was lucky not to drown – with its subtitle “A Heart Play,” pertains to an image of John and Yoko – the one on its cover - far more readily than any underlying reality. I am not sure whether anybody who bought the record and wept over it, or who lazily listened to the record and issued a stern putdown, sensed the differential. Everybody saw a star, or stars, and not a human being, or human beings.

Interestingly, after Lennon’s death, Double Fantasy sprinted back up the UK album chart from 46 to 2, but then stayed in second place for seven weeks, behind Abba and then Adam and the Ants, before the success of “Woman” as a single finally pushed it to the top. Despite all the mourning, were people still suspicious of the record – or did they see Yoko’s co-credit and warn themselves off?

The record itself is nothing like what people thought it was, even the parts people think they know well. It begins with the lead single, “(Just Like) Starting Over,” its three tinkly bells bookending the three sonorous chimes of “Mother” a decade earlier, and the song soon reveals itself as an old-school midtempo fifties rocker – did Lennon ever escape the fifties, or want to? – sung by Lennon in his best echoey Elvis/Big O voice, wanting the old love, and maybe the old times, back (though the song could be said to be sung to the eighties, urging it not to repeat the mistakes of previous decades). It’s sentimental and wonderfully sung – Lennon’s voice is pretty much unchanged and still terrific – but is it quite the New Beginning it professes to be? As the song slowly fades, over airport Tannoy announcements, Lennon lingers on the phrase “starting over,” and just before the song disappears, embarks on a series of whimpering yelps reminiscent of the White Album version of “Revolution.”

But this does not even begin to prepare the unwary listener for the shock of the new that is Yoko’s “Kiss Kiss Kiss.” Saying much the same thing as “Starting Over” but with much more anxiety and desperation (“Why death?/Why life?/Warm hearts/Cold darts” – it is like Bowie doing the Plastic Ono Band), the singer’s register and delivery immediately summon up the first “It’s No Game,” while she herself seems intent on conjuring up everything that has happened since 1969 and saying “look, I invented this!” – the Slits, the Banshees, Lydia Lunch, the B-52s, even Eno’s “Driving Me Backwards,” all present and culminating in an outrageous sequence of carnal cries and orgasmic grunts as if to say: “See? I was right ALL ALONG.”

After an explosion like that, one almost feels sorry for contented househusband John as he settles into “Cleanup Time,” another amiable mainstream rocker which references the same nursery rhyme as “Cry Baby Cry.” Only briefly, however, because it’s clear that Old Grampa Rock actually fits Lennon like a comfy pair of carpet slippers; he sounds contented, undisturbed, wholly at ease – it is as if “rock” has finally come around full circle to meet and blend with his forty-year-old viewpoint (even if the musicians include the likes of Tony Levin, Earl Slick and stalwart Andy Newmark, all involved in other, more dangerous musical adventures; the horn section includes useful people like Howard Johnson, Seldon Powell and JD Parran) and he is perfectly happy paddling in the mainstream.

More so than Yoko, anyway, who with “Give Me Something” threatens to take over the album completely, or at the very least relegate John to the role of guest on his own record. Here her extended screeching reminds us that she helped invent Patti Smith, but her worldview is miles away from John’s rosy outlook; she sings, as elsewhere, as though knowing, and dreading, the fact that some sort of “end” is coming (“Give me something that’s not hard,” she asks, plaintively; something, perhaps, that is not cock rock but possibly female rock).

Next comes the big breakup centrepiece, John’s “I’m Losing You” and Yoko’s “I’m Moving On,” which segue into each other and boast the same riff, tempo and chord structure; slow, procedural, hammering. Casting their minds back to the “lost weekend” of the mid-seventies, Lennon growls and pleads in his best “Cold Turkey” tones – and I note that this is the second consecutive number one album to make a sardonic allegorical reference to a bandaid (“The wound’s deep but they’re giving us a bandaid,” Ice-T will rap on “New Jack Hustler” a decade hence) – and his shrieked, “Well, well, WELL!” tells us that we are back in 1970 primally screaming territory; it’s all a façade, the old demons haven’t been vanquished, but merely put to the back of the airing cupboard. Earl Slick’s guitar rises to meet bleeping electronic noises, and Yoko comes back with her solemn, stoical but hissily accusatory response, in which she, amid many vocal hiccups, calls John a “phony.” Just like Holden Caulfield did, and Mark Chapman would; it is beyond scary.

But the first side concludes with Lennon trying to convince young Sean that it’s all been a nightmare – those three bells ring again – and “Beautiful Boy,” with its deliberate Japanese constructs, is a lullaby of sorts, an opportunity for John to do “Good Night” – written as a lullaby for Julian, in 1968 the same age as Sean in 1980, and, as performed by Ringo and the Mike Sammes Singers at the end of the White Album, enough to give anybody nightmares – but this time get it right. Structurally the song is also slightly reminiscent of “I’ll Follow The Sun,” but note how at the end we get a segue of children’s voices, open-air sounds and distant electronica, replicating the infant memories of “Revolution 9,” all of which dissolve and atomise, as though none of it really existed.

Side two begins with “Watching The Wheels,” a “God” for a new decade, with a piano riff that cheerily inverts that of “Imagine,” in which John declares his principles; look, he’s happy off the merry-go-round, out of the business, baking bread, doing what he does, just let him be. Not the Walrus, still, but just plain John the expat Scouser. It was maybe too late for all of that, however; Chapman quoted the line “People say I’m crazy” when questioned by the police, and much too late for Lennon to be considered as anyone other than “John Lennon”™, The One With The Answer For Everything. “I just had TO let it GO!” he sings, angrily, toward song’s end, but nobody will let the image, Lennon’s “star” self, go anywhere; stuck in the Dakota, he knows he is in the prison built for him by people who claimed they loved him.

How dare you be just plain John Lennon, you phony, and not “John Lennon.”

John Lennon, shot by a madman who thought he was John Lennon.

Chapman’s shooting might have been the ultimate act of rock criticism; you come back with THIS? Have you not heard “That’s Entertainment” or “Music For The Last Couple” you think you’re John LENNON you Perry Como motherfucker BANG BANG

Taking it all too far, because “Beautiful Boy” is the one that has that line about life being what happens while you’re busy making plans.

In “Watching The Wheels,” he sings “I tell them there’s no hurry, I-HI,” and suddenly the ghost of Buddy Holly is in the room. As well as tinges of “Walrus.”

Yoko’s “Yes I’m Your Angel” is a charming twenties flapper romp; yes, a bit Nilsson, but Yoko’s carefree, almost random “Tra la la la la”s remind me that Clare Grogan will become a huge star before this year is out.

Altered Images, with their first single about dead pop stars. “You did love me, didn’t you? Don’t leave me dying here!”

“We believe in pumpkins that turn into PRINCESS,” she sings halfway through the song, “and frogs that turn into PRINCE.” Remember that for later on in the year.

Lennon whistles cheerfully, and atonally, in the background as Yoko shakes her head smilingly as if to say: “Oh, John, you’re such a damn fool sometimes – but that’s my John!”

“Woman,” much more earnest, with its whispered Chinese proverb intro, not so much a grown-up sequel to “Girl” (see, on the NME/Rough Trade C81 tape from the same month Double Fantasy went to number one, Scritti Politti’s “The ‘Sweetest Girl’” for that) but a resigned envoi to “Jealous Guy” and the spiritual partner of “Cleanup Time”; look, the song says (all this looking, like fans look at images of stars and think they’re human), I know I fucked up in the past, but hey, I’m sorry, let’s begin again, and a lot of the reason why this went to number one as a single – in Britain, the fourth Lennon single to top the chart in under two months (four? “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” was top of the unpublished 3 January 1981 list) – was that, somehow, this was a resurrection of the old, cuddly John, the one eighties people could still remember from the sixties, when the Beatles made nice, reassuring ballads that everyone could slow-dance to; this is a QUIET SCREAM FOR OUR GOLDEN AGE TO COME BACK, and it’s only listenable in that context, rather than that of knowing that it was not going to be the start of a new paragraph, or even an erasure of the seventies with all its fuss and bother, but the deadliest and coldest of full stops. Like “Because,” its beauty lies in the foreknowledge that it has been curtailed.

Then comes Yoko’s “Beautiful Boys” in which she addresses, in turn, verse by verse, the four-year-old Sean, the forty-year-old John, and men in general, the ones who could wipe the planet out with their stupid bombs. She acknowledges, as Lennon himself does in “Woman,” that he is still a child in an adult’s body, but as the song progresses her voice slowly becomes more accusatory and the musical background moves from dreamlike electronic swirls to more menacing and prominent electronic noises; the song itself becomes steadily more violent and disjointed.

John has his last full word with “Dear Yoko,” an ebullient fifties rocker – see what I mean – with a “ah-well, ah- well” purloined from the intro to “Rave On,” a Bo Diddley backbeat (just like the Ants), an uncredited fiddle (if fiddle it be and not George Small’s string synthesiser), all the time saying how much he loves Yoko and can’t bear to be without her, even for an hour.

Then he disappears from the record – for the most part – leaving the final two songs to Yoko. “Every Man Has A Woman Who Loves Him” has a pretty straightforward sentiment, but Yoko sings it in such an icy, neutralised tone that it becomes oppressive. The music is early eighties Talking Heads, squelchy electronics and bouncy beats, while Lennon’s backing vocal threatens to take over the song altogether at more than one point. Finally, the much-mocked (at the time) “Hard Times Are Over,” a blustery gospel waltz workout (and Lennon is still clearly audible within the gospel choir, but intangibly so, as though he is already a ghost) which isn’t really the let-them-eat-bagels panacea that critics thought at the time; on the contrary, Yoko is painfully aware that this renewal may not last, hence “hard times are over, over for awhile,” or “hard times are over, over for some time.” The implication being that more shit will happen – and so it turned out.

The problem in appreciating this record independently of its circumstances is not helped by the 2000 CD edition, which includes the numbing “Walking On Thin Ice” – the song John was working on the night of 8 December – and therefore turns the album into its own commentary, along with the Lennon piano demo “Help Me To Help Myself” (“But the angel of destruction keeps on/Houndin’ me all around”) which may well be his “Black-Eyed Dog.” So the album, as it was then known (though the current edition offers a stripped-down CD of demos and alternate takes of the songs, with the original album on a second CD), became its own chief mourner.

But listening to Double Fantasy does bring home the second lesson from 1980. It is like the two pathways towards the afterlife, one shining and golden (which, however, leads to Hell) and the other dark and indistinct (but leads to Heaven). Adam Ant’s songs are clarion calls, aware of the doom of their time but insistent on the need to move forward and start over, if necessary, no matter how challenging and pessimistic they may originally sound. Whereas John and Yoko’s songs, despite severe reservations, point to what looks like an optimistic future but then turned out (literally) to be a dead-end. Both records will colour much of what comes after them in 1981; and the two rivers will meet towards the end of the year, when an album will feature a song about, at least in part, Lennon’s shooting, but it’s an album which, in February 1981, is really still unimaginable. We will be going a lot further than you think. Whether we are wise enough not to confuse stardom with humanity may, however, be a different matter.

The image, on the cover, number one for Valentine’s Day; do not do as we have done. Even if we were the first to do it; how could we have known?

Sunday, 17 February 2013

ADAM and The ANTS: Kings Of The Wild Frontier

(#242: 24 January 1981, 2 weeks; 14 March 1981, 10 weeks)

Track listing: Dog Eat Dog/‘Antmusic’/Feed Me To The Lions/Los Rancheros/Ants Invasion/Killer In The Home/Kings Of The Wild Frontier/The Magnificent Five/Don’t Be Square (Be There)/Jolly Roger/Making History/The Human Beings

(Author’s Note: The above is the track listing of the original UK edition of the album; the US edition has a slightly different running order with “Making History” being replaced by the single B-sides “Press Darlings” and “Physical (You’re So).” In addition, initial pressings of the North American LP edition came with a bonus 7” of “Stand And Deliver” and “Beat My Guest.” The cassette version incorporated both songs into a completely different running order. To preserve sanity, I have based my comments on the UK edition.)

“Let me answer this bit, Ducky. The contemplation of me by you when a love-feeling comes leads you into that deeper, uncatastrophic madness of God-love. And when and after the whirling stuff has eased up to the surface, don’t you find me among the oozing froth and scum?...I wonder if ny feeling of need for you in me – a need for that you-quality, for you yourself, in me – is at all like your God-need, if your flesh-and-blood body was a part of my own body, like you have in some plant forms of life?”

(Stanley Spencer, letter to Hilda Carline, September 1945, quoted in Stanley Spencer: A Biography by Kenneth Pople, Collins, 1991)

“If you’re not aware of the History of Art, you’re in great danger of repeating it.”

(Adam Ant, interviewed by Mark Ellen in Smash Hits, 11-24 June 1981)

Stuart Goddard grew up in Cookham; in the fifties his lifespan would have briefly overlapped with that of one of his heroes, Stanley Spencer. Perhaps he would have been present amidst the crowds in Christ Preaching At Cookham Regatta had Spencer lived long enough to complete it. Maybe Stanley saw him wandering around Cookham High Street, one of many tomorrows, as he contemplated what to do about his series of spiritual tableaux, the church-house project, or, as he sometimes called it, “the Church of Me.”

Adam Ant, as Goddard grew up to become, was at his peak the epitome of the Church of Me in pop; with Marco Pirroni, and behind them a thousand other influences and records, they set about building a new house of worship because, well, what was the alternative? What’s the good of worship when you end up like Sid Vicious or Ian Curtis – the “big nothing” alluded to and sneered in “‘Antmusic’” is almost certainly connected to these people’s sudden nothingness.

In this house of worship, however, it was made very clear by its builders that this was going to be a church that would incorporate daftness, colour and fun. Away with dulled compromise – “Ninety eight point four’s the bore with twenty-twenty vision” says Adam in “Ants Invasion,” while “The Magnificent Five” is an extended jibe at, and gradual demolition of, the very concept of sitting on the fence.

There is not a moment on Kings Of The Wild Frontier when you are not aware, or being made aware, that this is a bold attempt to do, to create, something new. If 1980’s number one records were all about darkness and hopelessness – not all of them, maybe, but enough of them to make a difference – then Kings, at least musically, sends a bulldozer through all of it. To anyone stuck at the turn of ‘80/1, it took on the significance of a beacon, a guide out of the dark and into a new light…a New Pop.

I’ll make no bones about it; Kings, the biggest-selling album of 1981 and the longest number of weeks spent at number one since Grease, has long been a personal favourite, from the original 12-page booklet/brochure/catalogue inwards. It smelt new, never mind looked new; watching the initial performance of “Dog Eat Dog” on early autumn TOTP unlocked something in me, and I know in around a quarter of a million others, that, as the song suggested, had been long suppressed. It changed something in me that the kilts and mascara of Spandau Ballet, gusting their way through “To Cut A Long Story Short” on the same show a few weeks later, did not.

The puzzle is in what has become a rather muted long-term critical perspective towards the Ants and this album. Even back in 1985, in his reportage/elegy Like Punk Never Happened, Smash Hits reporter Dave Rimmer was rather sceptical about Adam; the book begins in earnest, as it should, with Ant and Marco in a parental semi-detached house somewhere in Harrow, somewhere in early 1980, eating cupcakes and discussing plans for a new Ant sound, involving the Burundi beat amongst other things. Also present at that meeting was drummer Jon Moss, who obligingly drove to Rockfield Studios to double up some drums for the single “Cartrouble” but turned down the job as full-time Ant. Even at that stage Ant was not messing about; ingloriously dismissed by Malcolm McLaren from his own band (which soon became three-quarters of Bow Wow Wow), he contacted Marco immediately and began to make new plans.

There was a race to beat Bow Wow Wow to get Burundi post-punk into the charts, and also a huge urge on Adam’s part in particular to get revenge on McLaren, to prove that he could do this sound and do it better, brighter and cheekier than McLaren could possibly imagine. And so it turned out; despite much press coverage and manufactured controversy, and indeed despite some at times magnificent records, Bow Wow Wow only made a fraction of the impact that the new Adam and the Ants made, and that only after the event (the cohabitation of “Go Wild In The Country” and a reissued “Deutsche Girls” in the Top 20 of early 1982 made for some interesting comparisons).

Because Adam – with the considerable help of Marco - had “it,” that aura inherent in all natural pop stars. 1979’s Dirk Wears White Sox, recorded with the old Ants, had done well on an indie basis (and has stood up with time; it’s impossible to imagine the early Franz Ferdinand not studying the record in depth), but that was no longer enough for the singer – no, what was needed was an all-out attack on, and eventual embrace of, pop, both visually and aurally. As well as conceptually.

So it is something of a surprise to find Rimmer, nearly twenty-seven years ago, being gloomily critical of Adam’s business sense and his post-stardom ways of doing business. As a Smash Hits staffer he may have been vexed by Adam’s people demanding at least twice the going rate to republish his lyrics in a magazine later decried by Paul Morley as being “glossed into a daze with their hippy parodies of teenage excitement” but since copies of Smash Hits were never given away for free, one can only conclude that Adam was firmly taking care of business – in interviews of the period, as Mark Ellen noted back in 1981, he could have given Stewart Copeland or Gary Numan a run for their money in this respect – precisely to avoid getting ripped off by another McLaren; as he got deeper into stardom, the received wisdom is that he loved showbiz far more than he had ever cared for “punk,” and ended up a symptom of the problem rather than a solution to it. Much the same argument is offered by Simon Reynolds, in his book Rip It Up And Start Again, in which New Pop is basically used as a punch bag to decry what it was presumed to have done to the spirit of punk or post-punk (whatever either would have meant).

I do think this conclusion seriously wrongheaded – it encapsulates a lack of understanding of the nature and execution of showbusiness, as if “punk” were some kind of untouchable Holy Grail of music with unassailable morals (it’s turned out to be our era’s Queen Victoria, a relentless back-harking reference point to describe times when things weren’t like “this.” Quite. The mid-seventies were, as I’ve said before, a horrible era to live through). Actually, the person of whom Adam most reminds me throughout Kings is Tommy Steele, the first British rocker to get a number one album. You may recall that “Tommy Steele” in the early days stood for the collaborative team of Steele, Lionel Bart and Mike Pratt, astute, knowing people who knew exactly what they were doing and how to make it work in the milieu in which they were confined.

(In fact, you could extend this comparison to cover The Duke Wore Jeans, that jolly nineteen-minute extended play of a Brit flick soundtrack, which I now see was Steele’s Prince Charming with its urge to take on multiple characters and points of view, to try new clothes and attitudes on, just as happened at Sex and Seditionaries and Blitz in the second half of the seventies. Indeed, in Adam’s 1982 solo number one “Goody Two Shoes,” the hook of “You don’t drink, don’t smoke – what do you do?” glances directly back at the “What Do You Do?” that two Tommy Steeles had sung at each other twenty-four years previously.)

Kings, however, is all about belonging, tribes, warpaint, identity, colour, newness – every one of its dozen songs plays like a manifesto. Yet despite Adam’s protestations that “cult” was just another word for “loser,” what is most remarkable about listening to the record now is just how uncompromising and challenging its overall sound is. In the Smash Hits interview cited above, Adam admitted to checking out completely “off-the-wall” music to absorb its influences, including jazz, tribal music and what he calls “patently dull vocal sounds.” Always looking for that one thing to take, redeploy and magnify. The 2013 listener marvels at how such extreme things as “Feed Me To The Lions” and “Don’t Be Square (Be There)” were bought, heard, loved and presumably absorbed by millions; Pirroni’s guitar is frequently so out there (despite his expressed distaste in 1981 for “freeform instrumentation”) that he makes Robert Fripp sound like John Williams.

Like the Avalanches of a generation later, Ant and Marco were gleeful pillagers, jolly scavengers, rescuing whatever they could from the smouldering bonfire of popular culture and recycling it. Much attitude from the New York Dolls, Roxy and Bowie (“Ants Invasion”), guitars from Eddy, Marvin and Morricone, chord changes from John Barry, a general fuck-you-ness from the Pistols – and it all, in late 1980/early 1981, made perfect sense.

“Dog Eat Dog” opens up the album and sounds like Mud playing Gun’s “Race With The Devil” (if you snigger at the thought of Mud being an influence on anybody, listen to “Tiger Feet” and especially “The Cat Crept In” and then try to snigger). Adam essentially tells you what they’re going to do and how it’s going to sound: “You may not like the things we do/Only idiots ignore the truth” the song and album begin, and it sounded like pop’s rebirth – coming so soon after that remarkable sequence of proto-New Pop number one singles which openly played with the notion of what a “pop single” could do (“The Winner Takes It All” – the singer subverting the song she’s been given to sing and turning a lament into a declaration of independence; “Ashes To Ashes” – a star tells his audience pretty firmly that whatever you liked before, that time is OVER; “Start!” – a record that debates directly with its listener about what a pop single can achieve, or even change; “Don’t Stand So Close To Me” – with its 26-second drone intro and not wanting to give the band’s fans the same old shit), it feels like a deliverance. Voices boom, as do timpani, and then whistles and whoops take over, just like the Ants are taking pop over.

I’m not going to say much about “‘Antmusic’” or the title track as they both reached #2 as singles, so Lena will be giving the songs a fuller analysis when she gets to them, but it’s enough here to note that the internal inverted commas of “‘Antmusic’” are probably as significant as those of “‘Heroes’” and “The ‘Sweetest Girl’.” Not that irony is an intention here - Kings may be one of the least ironic of number one albums – but that the ball which Robin Scott began to roll in 1979 with “Pop Muzik” is gathering speed, and that whatever “rock” or “punk” or even “the twentieth century” had to offer was no longer enough, if indeed it had ever been. Amongst the pictures accompanying the 2004 CD reissue of Kings is a still from the video to the title track; the five musicians are noticeably cramped in their visual field of space (and presumably also cramped by their video budget), but still the intention and bigness of the song ring out. “Kings,” the song, getting past its Chic/Sister Sledge reference (“We are family”), does demonstrate the fairly huge debt owed by the band to that Glitter thing, with its double drums and call-and-response routines; but both music and philosophy here are far more multidimensional and complex. Laments about whiteness and taming; who was really listening?

Getting past the hits, “Feed Me To The Lions” quotes the Lawrence of Arabia theme, while over a grind that recalls 154-era Wire, Adam questions the idea of “emotion” in pop (“Too emotional, am I?” he sings, accusatorily). “Los Rancheros” sees the Eddy-Morricone lineage being coloured in, with some great deep chants of “East-WOOD!” and “CLINT!” and Adam musing about “a new breed [who will] say welcome tomorrow instead of yesterday.” It’s been a long time since a number one album was this playful, or this sinister.

“Ants Invasion,” with its hapless protagonist endlessly searching for followers, or recruits, or perhaps just a new audience – note Adam’s recurring “wrong decision”s – reminds me that Kings wouldn’t, I suspect, have had the impact that it did have without the example of a parallel album from 1980, Searching For The Young Soul Rebels by Dexy’s Midnight Runners, another group led by a driven individual sick of what he’s been spoonfed and looking for newness and solidarity in unexpected quarters, regularly interspersed with comments, and at one point a monologue, directed towards the audience. The degree of commitment in Adam Ant and Kevin Rowland is certainly comparable – and so “Goody Two Shoes” could justifiably be said to be about both of them – but whereas Rowland looked to old Stax and Northern Soul 45s and used his low-set horn section (trombone, alto and tenor saxes, no trumpet) as, effectively, a lead guitar, Ant and Marco looked to everything and everybody else. This song follows most obviously in the steps of Bowie, including a ruminative acoustic interlude, but the expressed desperation (or elation?) is new.

Side one ends with “Killer In The Home,” with Adam again pondering the nobility of Geronimo over the riff from Link Wray’s “Rumble” – with some extraordinary guitar feedback in the middle section – before concluding that, actually, the killer IS the home. A complete rebuttal to the endless questing for home that has dogged number one albums these last dozen years. To achieve and change anything, you have to leave “home” – as I knew was very much the case in early 1981.

The title track opens side two, before moving to the magnificent “The Magnificent Five” which manages to paraphrase both Nietzsche (“He who writes in blood/Doesn’t want to be read/He must be learned by heart”) and Orton (“Prick up your ears”). Musically the song is schizoid, veering between almost insultingly jangly indiepop and vast protean irruptions of thrash.

“Don’t Be Square (Be There)” is one of the album’s best songs, scooting along on a proto-Orange Juice chassis of indie-funk before being thrown off course by Pirroni’s discursive guitar which gradually escalates to a tirade of white noise that would not have shamed 1970 Sonny Sharrock. All the while, unforgettable phrases pop up – “Music for a future age,” “Antmusic for Sexpeople, Sexmusic for Antpeople,” “You may not like it now, but you WILL!,” “We go like THIS *SKKKKKKKRRRHHHHNNNNNPPPHHZZZZZKKKK!*,” even “Dirk wears white sox!,” and, most crucially, “Get off your knees!” Rather than the huddled Abba masses doing sing-alongs in the nuclear bunker, closing down and in on themselves, the Ants want to break OUT, go OUTSIDE, and FIGHT BACK – and that is what 1981 audiences wanted; all of 1980 having built up steadily towards it.

Kings is also probably the most universal number one album since Pepper; kids would get things like “Jolly Roger” straightaway and sing along (and dress up), while grown-ups would smile at its metamorphosed Pistolisms (“It’s your money that we want, and your money we shall have!”). Although you could interpret this as Adam playing the double-bluff card – I note that on “Ants Invasion” he sings, “You want a thrill!/So you come and see me/A cheap line in fantasy” – it is more a joyous reclamation of punk, and its reduction to second childishness that had always been inevitable (the song plays like a punked-up Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich, and there is some delightful atonal whistling to see the song out); for some reason “Blow High, Blow Low” from Carousel springs to my mind.

“Making History” goes by on a custom-based Bo Diddley beat and partly revisits “Dog Eat Dog” but its lyric is among the gloomiest on the record, all about bad guys with varying degrees of authority killing good guys for their own good and not knowing who is who; there were enough 1980 suspects for the song’s subject(s) here, which may be why the song was nervously pulled from all US editions of the album (“and we call this making history”). “The Human Beings” ends the record with a nervy Adam, whose yelp sounds remarkably like David Byrne, solemnly intoning the names of various Indian tribes; no more needs to be said, and so it isn’t.

Kings Of The Wild Frontier is, as far as this tale is concerned, the official starting point of New Pop (it might also be the starting point of New Pop’s funny cousin, New Romanticism, but that’s another argument for another time). It sets down pretty firmly how things – ideally – are going to be, and at the time it was unanswerable. Michael Jackson was listening, and ‘phoned Adam to tell him so; many exhausted and impatient others were, too. It succeeds magnificently in feeding high art and higher philosophy to its eager, predominantly teenage audience – did any pop star hitherto have such determination as to create an entirely new audience for themselves out of scratch? – and also, as Jon Savage commented at the time, at leaving its century, looking simultaneously back, to pre-industrial times (worship of the noble savage, tribal rites, etc.), and forward, to post-industrial times, such that even when computers would put everybody out of a job, there would still be a societal umbrella (of “rejects”) for people to shelter under (and this nearly three years before the Smiths).

Moreover, I think that no number one album since Please Please Me had managed to convey the immediate impression that This Is The New Thing and You’re All Welcome To It (you certainly couldn’t have said the latter about Never Mind The Bollocks). No number one album since then had drawn such a decisive line between the past and the future and called it the present. It is as if this record had somehow been summoned up, spirited up, by common, unheard prayer. It is the explosion which 1980 had predicated all along.

That it was also Adam’s only number one album is almost incidental in this context. As New Pop gathers pace, it will become customary for its leading lights to get just one number one album (if they are lucky) and nothing else. In truth Adam was unlucky with Prince Charming, released in November of the same year and if anything a more uncompromising album (“Ant Rap” remains one of the most extreme singles ever to go top ten; “Flowers Of Romance” gone pop), which unfortunately came up against entry #256. Perhaps there were seeds of suspicion in his audience even then; exactly where are these Ants taking us (no matter that, in the video for “Prince Charming,” he effectively invents vogueing)? In his subsequent career(s), the world was not uniformly nice towards Adam, but he has survived and recently released a new album, still raging at injustices, looking askance at his, and rock’s, past, still trying to find ways out of settling for mediocrity.

As for 1980’s legacy to 1981, the former year did arrive at two conclusions. One was that, if this was “the end,” it was necessary to fight one way’s through and find, or create, a new “beginning,” even if from songs which lyrically and schematically weren’t always optimistic.

The other conclusion, or the other lesson to be learned from the end of 1980, you may discover in the next entry.

Wednesday, 13 February 2013

ABBA: Super Trouper

(#241: 22 November 1980, 9 weeks)

Track listing: Super Trouper/The Winner Takes It All/On And On And On/Andante, Andante/Me And I/Happy New Year/Our Last Summer/The Piper/Lay All Your Love On Me/The Way Old Friends Do

She stared at the songsheet in open-mouthed disbelief. They hadn’t been speaking or socialising much of late; how could they, having divorced the year before – any association was now purely professional. As professional as she always was, however, even she found it hard to be compelled to spend so much time with people to whom she was no longer that close – days in the studio, months on the road – and yes, it did hurt.

Note how in the film Citizen Kane the camera is consistently drawing the viewer in through a miasma of darkness to focus on a central ring of light. It is a simulation of the spectator walking into the cinema and realising, too late, that they are sitting in the dark, perhaps alone.

There is the ring of light, slightly north of the centre of the cover picture, and although the spotlight is not a “Super Trouper” as such, it is shining very firmly on the four musicians, all obligingly dressed in white (this is one way of interpreting 1980’s number one albums, a constant battle between dark and light). The women are smiling, but rather grudgingly so, as if they had to smile; the men are not smiling at all. None of them is looking at us.

Who are these people surrounding them? Acrobats, jugglers, fire-eaters, possibly a soldier (where did he come from?) In front of them is what might be a velvet rope, or perhaps the boundaries of a boxing ring, or maybe even a primitive stocks. They are all applauding the musicians; on the rear sleeve, the positions are reversed, and the musicians are now applauding their audience. The rope, or whatever it was, appears to have been removed.

Although this scene is highly reminiscent of a music video which is still some time in the future – in 1980, not even the song has been imagined – it was actually a compromise; the original idea was for the musicians to be surrounded by circus performers in the middle of Piccadilly Circus, but Westminster Council said no and thus robbed us of what would undoubtedly have been one of the great London album covers. Hence the group retreated to a film studio in Stockholm, rounded up the members of two local circuses, and the pictures were taken.

They could therefore be in the middle of nowhere. Or in the middle of the road, which puts you at far greater danger of being run over.

The fun seemed to have disappeared from their music, too. It was hard to believe that it was less than five years since the glee of “Mamma Mia”; harder also for the men to cope with the fact that it had now been well over two years since they’d last had a number one in the country they called “the home of pop.” Oh, all the intervening singles had gone top five, of course – they’d hardly vanished from pop – but there seemed something stilted about the treading of commercial water, as though they were forcing themselves to go disco. Well, where else could they have gone? A punk Abba? How sad a joke would that have been? So they’d tried different gimmicks – their first 12” remix (“Voulez-Vous”), giving Björn a lead vocal on a single (“Does Your Mother Know?”), even trying to conjure up the Hootenanny Singers ghosts of old youth with “I Have A Dream.”

If the twenty-one albums which went to number one during 1980 tell us anything, it is that there were two distinct, perhaps opposing tendencies among two distinct, perhaps opposing groups of record buyers. The Woolworth’s types who didn’t really buy records as such but wanted something easy, familiar and reassuring, and the more exploratory, impatient types looking to break the mould of complacency and reach out towards something they might call a future. It’s hard to imagine who would have bought both Sky 2 and Back In Black, or The Magic Of Boney M and Telekon.

But Super Trouper sold more and stayed at number one longer than any of them, and I suspect that not only is it the record that brought these two factions together, but it might also be the year’s most frightening and disturbing number one album.

Now, the “I Have A Dream” thing, the guys had been particularly upset about that one. It was a return to the nicer old days – or so they’d hoped - and there was the children’s choir and here was the irresistible chorus to a song designed to be number one at Christmas. But then those bastards Pink Floyd, who NEVER released singles, suddenly put one out with their own children’s choir without warning! They shouldn’t say that about groups like that, they knew; still, it was difficult to maintain a straight face after reading Roger Waters saying that he’d gone off Abba about five seconds after he’d first heard them. That was a kick in two heads, but still they had to grin and settle for second place over the season.

Abba in second place to anything or anybody! The crass impertinence!

Let’s start, as the album does, with the title track, which, as a single, became their ninth and final UK number one. The last wave of the old, jolly Abba – at least until you listen to what they are singing.

“Super Trouper,” the song you think you know so well.

A song which, from the off, warns that the beams of the titular spotlight “are gonna blind me” and goes on with words of the calibre of “I was sick and tired of everything,” “Wishing every show was the last show,” “There are moments when I think I’m going crazy,” “The sight of you will prove to me I’m still alive.” A song which alters its musical backdrop, so that the verses are predominantly acoustic and introspective, while the choruses are brilliantly shined and outgoing.

But you can sense the group are struggling to keep, or make, things the way they had once been; the Glasgow namecheck ensured that the song was especially popular in Scotland (and, as a minor bookend, the most famous Scottish version of “The Way Old Friends Do” is by the Alexander Brothers, who in 1964 sold more copies of their “Nobody’s Child” single in Scotland than anybody else, including the Beatles) but I wonder how well, if at all, Abba knew the dim and dismal Glasgow of 1980; eight months later, another single inspired by the same city would go to number one – “Ghost Town” by the Specials.

Nevertheless, who is this “you” in the crowd? It can’t be the singer’s lover; wouldn’t he be backstage, or sidestage, watching her sing close up? “Facing 20,000 of your friends,” sings Frida, “how can anyone be so lonely?” If we are not far away from Gary Numan territory here, the song at least admits the possibility that it’s the fan, the listener, who keeps the musician going, wanting to breathe, and so reaches out in a way that a 1980 Numan couldn’t or wouldn’t.

The key line, however, is: “All I do is eat and sleep and sing,” and I wonder whether Voulez-Vous wasn’t simply a red herring or a delaying tactic; you may recall that the preceding album concluded with the horrifying “I’m A Marionette” and Super Trouper, the album, appears to be taking its lead from there. This is what happens when musicians turn, or are turned, into mocking puppets; this, Abba imply, is how we really are, what we truly feel.

And it’s not pleasant.