(#44: 25 December 1965, 8 weeks)

Track listing: Drive My Car/Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)/You Won’t See Me/Nowhere Man/Think For Yourself/The Word/Michelle/What Goes On/Girl/I’m Looking Through You/In My Life/Wait/If I Needed Someone/Run For Your Life

One of the pitfalls of being an experienced (or possibly over-experienced) listener is that when it comes to a literal re-view of albums long since acknowledged to be “landmarks” or “classics,” one sometimes takes refuge in a bizarre mixture of trepidation and cynicism; the gimlet eye aimed at its subject, the mouth silently accusatory – come on then, prove yourself; are you really as good as all that? This tends to be a convenient mask for the writer’s incipient dread at having to think of something new to say about it.

Immediately we cruise into the sternly optimistic highway of “Drive My Car,” however, such fears dissipate. The sonic difference between this and the previous five Beatles albums is something akin to the changeover from black and white to colour television; every sound is now crisp, direct and still startlingly modern-sounding. The Beatles themselves sound, perhaps for the first time, genuinely liberated, in that they have begun the process of liberating themselves from their hard-cast images and now seem free to write and sing about anything and anybody they like.

Moreover, “Drive My Car” marks a key step forward for Lennon and McCartney as composers in that it signifies a move towards the observational, a shift from general love/woe songs to sharper-focused character studies. This may have been in part inspired by the examples already being set by the likes of Pete Townshend and Ray Davies (although their best examples come from 1966 onwards) but musically there is a wider curiosity at work; struck by the militantly spontaneous polish of Otis Redding’s “Respect,” Harrison suggested it as a model to McCartney in terms of arranging “Drive My Car,” and McCartney’s gobstopper-profound bass drive throughout the track (as well as his own funky piano vamps) indicates how well he absorbed its lessons. Both Paul and John shriek their way through the song’s accumulating double entendres as though it were Christmas morning (so it is fitting that Rubber Soul ascended to number one in Christmas week), while George’s askew (and possibly varispeeded) guitar solo takes the music hall into the arena of the surreal.

If the Beatles were hardening up in the face of the Who, the Kinks and the Animals, however (not to mention the Stones), then they were similarly softening up in the prospect of the Byrds. That Harrison’s initial interest in Indian music was sparked off by doodling on a sitar he found in the props room while filming Help! is well known, but his deeper interest – the first manifestation of which was his playing and Lennon and McCartney’s writing on “Norwegian Wood” – was ignited following a long night in the company of Roger McGuinn and David Crosby when things to do with the raga were discussed and demonstrated. But while “Eight Miles High” proved that McGuinn’s mind was more on Coltrane’s mutation of the raga form, Lennon and McCartney preferred to subvert the folk song from within. Overall there is not much direct evidence of Dylan’s influence on Rubber Soul – though Dylan’s “Norwegian Wood” send-up (“4th Time Around” on Blonde On Blonde) suggests a coolness towards the record on his part – but “Norwegian Wood” uses Dylan’s bleakly dark comedy (Lennon’s markedly Scousean “rug”) to take the “Baby’s In Black” sea shanty trope to less fathomable depths, its vaguely grotesque punchline giving the impression of Roald Dahl dabbling with the Dorian mode.

In any event, both of these “comedy songs” (as its composers described them at the time) seemed new, astonishing, and perhaps a little unsettling, to Beatles followers, and if they had been pushed to some extent into raising their game, they met the challenge with wicked aplomb, to such an extent that even the record’s lesser songs are pulled into its ascending orbit. “You Won’t See Me” sees McCartney using the same chord sequence as “Eight Days A Week” (and, metaknowingly, the Four Tops’ “It’s The Same Old Song”), and is the strangest of his “Asher” songs to date; a chirpy major key melody and arrangement (those “oooh la la la”s which Steve Harley would use a decade later on “Make Me Smile (Come Up And See Me)”) hiding a lyric which veers between admonitory and suicidal, ironically decorated by one of Harrison’s most ringing and transcendent Stratocaster solos, its progressively ascending bell chimes resolving in a doorbell-to-heaven false high note peak, which in turn is subverted by Mal Evans’ malevolent high A organ sustenato throughout the final verse and chorus, a gratingly sniggering reversal of the high A lead violin sustenato throughout the final verse and chorus of “Yesterday.” As though to prove McCartney’s claims to invisibility, Lennon uses almost the same backing vocal trick (“ooooh-la la la la”) on “Nowhere Man,” less a putdown of the hapless 1965 George Mitchell Minstrels fan, more a carefully tender assassination of his own Weybridge self., the final bullets shooting from between the laughingly clenched teeth of his final “NO, BO, DY!”

Then it’s George’s turn to address nothingness; “Think For Yourself” is the first of his half-formed but surprisingly aggressive addresses to The Man, sneering about “the ruins of the life that you had in mind” as two McCartney basses buzz around him, the more prominent fuzzed-up and mixed to the forefront of the picture (fourteen years before Unknown Pleasures). The rhythmic rush is Motown-ish, the ending sharp and abrupt and the general tenor nudging in the direction of Mod.

The Mod flower is blossomed open in “The Word,” for me Rubber Soul’s standout and most forward looking track; a brilliant, stuttering rhythm, half Pickett, half “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag,” a swooning joint lead vocal by John and Paul, falsetto octave-doubling passages which could pass for gospel, even a hint of ska shuffle and endless decorations of arrangemental interest, including McCartney’s schoolteacher piano introduction and George Martin’s walrus-like harmonium interceptions midway – and, above all else, the flowering optimism: “Say The Word and be like me,” “Have you heard, The Word is Love!,” “I’m here to show EVERYBODY the light!” A shivering frisson of shiny yellow descents through the “So fine/Sunshine” couplets, 1967 announced with just over a year to go.

After that peak it’s back to the “comedy songs,” though McCartney’s cod-chanson “Michelle” manages to transcend its pastiche status through the writer’s studiously earnest vocal – he keeps the straightest of faces through the Nina Simone “Spell On You” quote and also the line “I think you know by now,” while his solo, possibly on speeded-up bass, foretells the Hugh Hopper of Wyatt’s “Alife.” There is only the faintest hint of a protruding tongue. Ringo follows with his feature “What Goes On,” a perfunctory but cheerful stroll through avenues of C&W betrayal, George going through the Chet Atkins motions.

A deeper humour reveals itself in Lennon’s “Girl,” the most peerless of songs about the thing rather than the thing itself (or herself). If the Green Gartside of 1985 knew how to play the listener and the camera with his deconstructions, then here are its roots; Lennon’s melodramatic indrawn breaths (of wonder or exhaustion?), the manner in which he steadily reveals that the girl is indeed no ideal, insofar as his dreams include, for the first time in three Lennon songs on side two of Rubber Soul which deal directly with death, the notion of mortality; his tropes move as seamlessly and sneakily as “The ‘Sweetest Girl’” would move from bubbling gum to revolution, the song’s Greek taverna stranded amidst a bier keller march more emphatic and less ironic than McCartney’s Seine reveries.

McCartney returns for “I’m Looking Through You” – now it’s “Asher” who is invisible, and McCartney’s voice is high in register, indignant in emotion and vituperative in its accusations. “The only difference,” he sneers at one point, “is that you’re down there,” prior to concluding, with a moderately terrifying euphoria, “And you’re NOWHERE!” (i.e. she’s the real Nowhere Girl) – again, the song’s emotion is subverted by the song’s bright swing, its sunny twists directly predicating the Monkees, especially Ringo’s minimalist Vox Continental organ riff and supporting tambourine.

Then we come to “In My Life,” Lennon’s “Yesterday” and the most profound song any of the Beatles had yet written. Much of its profundity stems from its considerably slimmed-down prolificity; Lennon originally conceived the song as a long-form epic memoir of childhood Liverpool but eventually pared it down to its emotional elements, and for the better. For the first time he faces down his loves and demons, and refuses to be wiped out by the things which once might have wiped him out. Moreover, he stays perfectly calm while doing so (although suppressed hyperactivity is implied by Martin’s sped-up electric piano-as-harpsichord pop-up interlude), the only crack in the façade coming with his final, whimpered, impossibly moving “In my life” for which the entire song stops. The past is what it was and will always be, but it’s who and what are here now that matter; cutting himself from his past is palpably akin to cutting off at least one limb, but he knows that death (“Some are dead and some are living”) is not – yet – an option. As indeed did the young man in Los Angeles who would listen to this album, and in particular this song, with untold wonder, such that he knew that he had to produce something at least as profound and radical in order to survive.

Thereafter, however, Rubber Soul becomes curiously unresolved. “Wait” is a sombre variant on the Stax/”Drive My Car” model with gloomily descending minor chords and a manfully valiant attempt at an upbeat chorus. Still, Lennon’s concluding “Oh, how I’ve been alone,” reveals an exhaustion and oldness beyond his years, as McCartney’s bass rallentandos to a rumbling rattle beneath him like a disregarded Tube train – even though the song is purportedly about coming home. Harrison’s “If I Needed Someone,” in which his Rickenbacker Fireglo 12-string is more assertive than his voice, is the album’s clearest debt to the Byrds (in particular, “Bells Of Rhymney”) but as an exercise in sustained self-denial rivals as well as precedes (by a decade) “I’m Not In Love.”

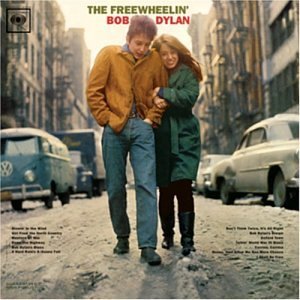

Lennon provides a peculiarly unsatisfying ending to the album with “Run For Your Life,” the third of his triptych of death-related songs and perhaps the starkest – “I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than with another man” was originally from Elvis’ “Baby Let’s Play House” but Lennon runs it into a grassless knoll of low-spirited rock, markedly lacking even the character or energy of his “Dizzy Miss Lizzy.” It runs morosely around its self-constructed circle of jealousy and is most notable for Lennon’s first clear admission of same (“I was born with a jealous mind”) and the curious glee with which he chews off the end of each chorus (“Thatssszeend-UH!”). Best viewed, perhaps, as a final glance towards a past he was so keen to forsake (but since he was yet to meet Yoko, possessed no real means of doing so), but the final petering out of Rubber Soul (which could easily have been solved by more judicious track selecting and sequencing) should not detract from its immensity as a whole. On the cover the group are still in the park, but now through a deliberately distorted lens, staring down at us just as they had done on the front of their debut; are we watching them or are they merely imagining us? God only knows.