(#370: 27 August 1988,

4 weeks; 19 November 1988, 2 weeks)

Track listing: I

Should Be So Lucky/The Loco-Motion/Je Ne Sais Pas Pourquoi/It’s No Secret/Got

To Be Certain/Turn It Into Love/I Miss You/I’ll Still Be Loving You/Look My

Way/Love At First Sight

“Watching Alice rise year after year

Up in her palace, she's captive there”

(Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds, “Watching Alice,” from the

1988 album Tender Prey)

Neighbours

premiered on BBC daytime television on Monday 27 October 1986, just over

fourteen years since restrictions on daytime television hours had been lifted.

ITV had taken immediate advantage – Emmerdale

began as an afternoon soap – but the BBC, fatally cautious as ever, hummed and

hawed and tentatively set about developing Ceefax. In actuality October 1986

was a fitting time for daytime television to find itself; it was slowly and

perhaps grudgingly acknowledged that its captive audience not only included

children, pensioners and young mothers and/or housewives, but also the

long-term unemployed. There was still reckoned to be enough slack in the

capitalist system for something approaching a “dole culture” to be sustainable

(although this turned out to be an illusion, built on a combination of reckless

City speculation and one-off episodes of large-scale Government expenditure; by

1987, under media pressure and with another General Election looming, the slow

clampdown on all of this had begun).

The daytime programming on offer on BBC1 was not reckoned to

be much beyond filler status. Indeed, the first Monday’s programming began with

a grotesque “documentary” which should never have been allowed to happen – the title

Who’s A Pretty Girl, Then? has already

told you much more than you need to know – followed by a curious mixture of

public obligation broadcasting (a programme for the disabled entitled One In Four, an unexciting-sounding

televised ‘phone-in show called Open Air,

which involved a very young Eamonn Holmes) and children’s television (Play School, Henry’s Cat, Phillip Schofield, an edition of The Clothes Show which I will likewise try to pretend never

existed) mixed with fairly random stuff – a Gardeners’

World special from Pebble Mill, a rerun of The Onedin Line, a Rhoda

spinoff called Valerie (which also

featured a very young Jason Bateman),

something called Star Memories

(wouldn’t happen now) in which Nick Ross asked Su Pollard about her memories – plus the obligatory news and weather

bulletins, and right in the middle of all this, at 1:25 pm, Britain’s first

view of Neighbours.

In truth it should have been considered for a teatime rerun

right there and then, rather than what was

on at 5:35, namely Masterteam with

Angela Rippon (“Will the MICKLEBARROW MORRIS MEN dance their way to gold

tonight?”), but that didn’t happen until the beginning of 1988, by which time

it had become clear that the soap was astonishingly popular. Paul Morley

describes Neighbours as being “a

virtual matrix of all the differences in white Australia” and really it was not

very much; devised by Reg Watson, who in a previous ATV life had helped

formulate the notion of Crossroads,

nothing much happened in its episodes other than endless sunshine and barbecues

as well as minor drama, the endless chronicling of love lives and the learning

of lessons. One felt that this was what might be offered on the Village’s

television channel, and what world, if any, lay beyond the partly

anagrammatic Erinsborough?

Kylie Minogue came into the series some time after this –

she had begun working on Neighbours

in April 1986, but these episodes didn’t filter down to British television

until much later – but her Charlene Mitchell instantly became one of the show’s

most popular characters, essentially a portrayal of a girl who didn’t want to

be portrayed as a “girl” (her eventual trade was as a welder). In 1987 she

appeared with other cast members at a benefit concert for a local Australian

rules football team and performed “The Loco-Motion.” Much to her surprise this

went down a storm and the demand for a record rose. When released – as “Locomotion”

– it topped the Australian charts for seven weeks.

The record had come about because the Stock, Aitken and

Waterman team had sent one of their engineers – a Canadian named Mike Duffy – to

Australia as part of a work exchange programme. While there, Duffy produced “Locomotion”

in what he felt was the trademark SAW style, and telephoned Waterman to let him

know how the record had done and play it to him. Waterman was amazed by the

news but distinctly unimpressed by the record – “The Loco-Motion,” as performed

by Little Eva, was one of his favourite pop songs – and when Minogue eventually

came under SAW’s direct aegis, Waterman made sure that the song was

re-recorded.

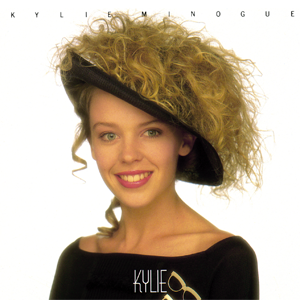

In 1988, no album sold more in Britain than Kylie – to date it has gone seven times

platinum – and few 1988 number one albums give me greater headaches. As you may

have guessed, I have had some considerable amount of time to think about how to

approach this record, and at one stage I planned it to be the centre of an epic

rant about false memory syndrome, the decline of the British music press and

the pandering to a white, male, middle-aged, middle-class audience of consumers

endemic in both. All that was needed was for the record to be great, greater

than all those “classics” nobody wanted at the time but which everybody now

professes to have “loved.”

The trouble is, yet again with the twenty-year-old Kylie,

there really isn’t any “there” there. But a greater difficulty lies with the

approach of SAW. I understand their late eighties function as a sort of walk-in

Hits 4U facility, their renegade status as independent operators with

comparatively limited facilities who could compete on equal terms with, or even

outdo, the corporate majors – and this best asserted itself in their dozens of

fine singles.

With Kylie,

however, the problem is much the same as was the case with Rick Astley, namely

that SAW weren’t very good at albums. Here we have an album utilising the

standard pre-Beatles formula of half-front loaded hits, half-filler, containing

four top two singles and three pop classics of which any musician would have a

right to be proud – “I Should Be So Lucky,” “Je Ne Sais Pas Pourquoi” with both

subject matter and enigmatic chord progression worthy of My Bloody Valentine,

and “Turn It Into Love,” where for once Minogue sounds committed to something,

emotional – but further delving reveals there still to be flaws; Hazell Dean, I

recall, endured some terrible stick from Kylie fans about "stealing her song"

and never had another Top 40 hit thereafter, and although SAW provided Dean

with a very different arrangement of the same song, I wonder whether Dean’s

hearty decisiveness isn’t actually more suited to the song’s emotional tenor.

Certainly no outraged Mandy Smith fans expressed concern about Kylie doing her “Got

To Be Certain” (which admittedly would have been unlikely, as Smith’s version

was not commercially released until 2005).

But the rest of the non-single work here is simply dull,

uneventful, so much so that their ennui

envelops even the hits. The problem is not that Kylie is too poppy – conversely, it’s not poppy enough. There’s always the shade of SAW’s

ingenuity poking through here and there – the unexpected harmonic diversions

throughout “It’s No Secret” (the closest the record comes to Motown), the odd

jelly plate of wobbling bass which grumbles throughout “I’ll Still Be Loving

You” – but things like “I Miss You” aim for bland jazz-funk AoR which was

certainly not SAW’s strong point, while “Look My Way” resembles an offcut from

the first Madonna album five years too late.

More concerning is where, if anywhere, Kylie herself is in

all of this. The record was quite clearly and squarely aimed at teenage girls

and I don’t think that at this late stage of our civilisation further white,

middle-aged, middle-class male critical output is needed. But so many of these

songs – none written by the singer herself – set her up as a kind of pop

doormat; she is forever being used by him, or only dreaming of him, or

frantically and needlessly apologising to him (which is what her “Turn It Into

Love” is really all about). And there is nothing in her voice, which is

indistinct, feathery and sometimes inscrutable, to suggest what she plans to do

about all of this mess. She certainly doesn’t sound like a singing actress, or

even like the former child star that she was (The Sullivans, The Henderson

Kids) struggling with the notion of growing up – it should be noted that in

1988 alone, Tanita Tikaram was a year younger than Kylie when she released Ancient Heart, and Debbie Gibson was

two years younger when she put out Only

In My Dreams – albums whose songs were written by the artists themselves.

Really she doesn’t sound like much of anything, and her

robotic retread of “The Loco-Motion” indicated that Waterman was right to be

uneasy about revisiting the song, which in its 1962 original was composed, as

Dave Marsh put it, of lots of little sounds which in themselves didn’t mean

very much but when compressed together sounded like the biggest sound there had

ever been – and in the late 1962 context of nuclear uncertainty and emerging girl power probably sounded like a (happy) explosion (the low sax harmonies

resemble a bagpipe drone). But in 1988, 1962 was already a long time ago, and

putting together jigsaw pieces of voice-tracking over a determinedly anonymising

dancebeat was no substitute for what the original had suggested. Here it is

just another harmless suburban nightclub floorfiller for the unfussed – a description

which couldn’t be applied to the single which kept it off number one – and, as

with the rest of this record, does nothing to suggest that this was somebody

who would go on to have number one albums in four different decades…and

counting. “How would the 12 labours of Hercules compare with the toil of Terry

thrice weekly?” runs the description of the Wogan

chat show as broadcast on Monday 27 October 1986. Or the toil of working out

what can’t be got out of Kylie Minogue’s head? Even the alleged happy ending of "Love At First Sight" - not the last time she would record a song of this name - is disturbing in the context of what has preceded it. Nick Cave's "The Mercy Seat" - most music critics' idea of 1988's best single - is really no more than a crudely-disguised paranoid Motown stomper which R Dean Taylor could have pulled off with great bubblegum aplomb, but its careful and gradual self-obliteration, of both self and truth, is perhaps more in keeping with Minogue's "Been hurt in love before/But I still come back for more" than is comfortable.