Monday, 12 July 2010

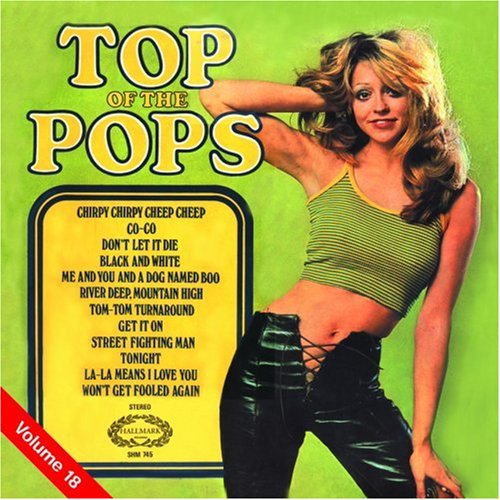

VARIOUS ARTISTS: Top Of The Pops Volume 18

(#96: 21 August 1971, 3 weeks)

Track listing: Get It On/River Deep, Mountain High/Me And You And A Dog Named Boo/Don’t Let It Die/Tonight/Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep/Co-Co/La-La Means I Love You/Street Fighting Man/Tom-Tom Turnaround/Black And White/Won’t Get Fooled Again

No, this isn’t Groundhog Day, although you would be forgiven for thinking that; seven of the songs on Hot Hits 6 reappear here, and the competition was obviously fierce. The tracks don’t bear extended analysis in or of themselves, and I will merely say that overall this is a “better” record than Hot Hits 6 in that it is technically more competent and more readily achieves its central aim of sounding as much like the originals as possible, although it should be understood that all such assessments are relative. Of Martin Jay, the chief male session singer on the record, it can be said that, if nothing else, he tries his best; his Bolan on “Get It On” sounds in places like Paul Haig though not especially Bolanesque, his attempt at doing Daltrey on “Won’t Get Fooled” is foolhardy but brave – those “yeaaaaahhhh!”s can’t really cut it, but then he hasn’t lived Daltrey’s life – and (if it is him) his Hurricane Smith on “Don’t Let It Die” and Roy Wood on “Tonight” bear a striking similarity in approach and phrasing to both Ian Hunter and David Bowie, so much so that I briefly wondered whether it was in fact Bowie paying the bills. Against this, it should be pointed out that the male voice on “River Deep” sings much more like David Stubbs than Levi Stubbs and that no one has satisfactorily worked out the wide vocal range required for “Tom-Tom Turnaround.” Of the female singers, one Jacqui Baxter makes the best impression, again on “River Deep,” while the performance of Barbara Kay – also the main vocalist on the Piglets’ “Johnny Reggae” – on “Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep” is stunning, in the manner of a taser gun.

The doleful bass voice we hear at the beginning of “Tom-Tom” was that of Bruce Baxter, who along with producer Alan Crawford was the main man behind the Top Of The Pops series, undoubtedly the market leader in the soundalike compilation stakes. Turned out, as were the Hot Hits albums and all of their sundry imitators, on the turn of a dime, with each performer allegedly given fifteen minutes per song to nail down a usable vocal track, and a deadline of one week to put the entire album together (song selection, arrangements, recordings, mixing, packaging), they were of the “now”; a glance at the singles charts of August 1971 reveals that virtually all of these songs were climbing. So the prospective purchaser was presented with a deceptive but attractive package; with characteristic idiocy, the BBC had neglected to copyright the Top Of The Pops name and thus most buyers assumed that these records were directly connected with the show and that they must therefore be the original versions – but even if they weren’t, and they knew they weren’t, what did it matter? I’ll come back to that crucial question shortly. Nonetheless, here were all the hits of now – or at least the easiest hits to cover (no “In My Own Time” or “Devil’s Answer” to be found here) - conveniently and cheaply packaged for the impoverished or casual music consumer; none of the waiting time for singles sales to pass their peak before major labels would consider packaging the originals. For millions, or at any rate thousands, it was irresistible.

The brief sleevenotes were typically hyperbolic, claiming eternal fealty to their audience (“We’re so thrilled we want to climb the highest mountain and shout the good news to all the world. Thanks again, you lovely Pop fans…” exclaims the note to Volume 18), perhaps drawing them in on the friendly conspiracy; come on, they’re not the originals, but we’re doing our best, isn’t that what being British is all about, mucking in?

And maybe – accidentally? – developing or redeveloping the art and purpose of the English folk song, because there are ramifications here which can’t be avoided. Looking at the remarkable success of these records begs some key questions, not the least of which is: what, and who, is music for? Remember that in the days before "the record" took hold of the market – and some considerable way into those same days – the song, not the performer, was predominant, the thing which attracted us. Even when the singles chart commenced at the end of 1952, record sales were very much a minority; sheet music was dominant, a harking back to the time when every family’s parlour bore a piano, when a family would learn to play the piano, sing these songs in their own homes, or in the pub. Delving into the early days of the singles chart, the commonest phenomenon is that of several competing versions of the same song; everyone had their individual preferences, but the song was the common/unifying factor.

People like Elvis and the Beatles detoured us. We grew to think that now the artist was the thing which mattered, the song secondary, the growth of individualism, the decline of familial and societal bonds (even if few artists did more than Elvis or the Beatles to unite the disparate strands of their multiple followings). And we decided that we had to take music seriously, to pin it down and analyse it, connect it to what else was occurring in the world, anybody’s and everybody’s world.

But the non-specialist consumer continued to confound these ambitions, and in various important ways still does. What we have to bear most importantly in mind – and this is common sense rather than revolutionary theory – is that most of us aren’t that bothered about music. Oh, we love it, couldn’t really do without it – what do these forty million people who never listen to music do with, or to, themselves? – but, as Tim Rice pointed out long ago (his introductory note to the 1981 edition of the Guinness Book Of Hit Singles, to be exact), the sheep get separated from the goats at around the age of eighteen – most people then relegate music to the background of their lives, but a small number of obsessives remain spellbound by music, feel the need to go even deeper into music, to keep up with new developments, to retrace histories.

But we continue to sing songs and like songs, be momentarily transported by songs, and it’s that residue which provides the main bloodstream in which music is actually able to live and survive. To connect all of this back to things like the Top Of The Pops series, a song catches the ear of a potential record buyer, and they like the song – it’s catchy, stays in their mind, they unconsciously whistle it while making breakfast – but they’re not particularly concerned about the backstory of either the song or the singer, unless the latter is a major figure; and even then they’ll allow some slack. They can’t necessarily afford to buy everything that makes the Top 40 on a weekly basis, but if they see twelve current songs they know in an inexpensive and reasonably attractive package, they will settle for them. Operators such as Alan Crawford and Bruce Baxter recognised this semi-silent majority and aimed their product at them with fair accuracy.

What would an owner of Top Of The Pops Volume 18 do with the record? They’d keep it in the cabinet, bring it out as background music – this music is purposely designed not to intrude into the foreground, not even when attempting “Street Fighting Man” (of which latter it can again be said that the musicians do their manful best, although the vocal is taken too slowly and the original’s essential swing and bounce are absent) – have it on at parties, absently or not so absently sing along to it, maybe conveniently lose it in the attic a few years later before taking it down to the charity shop. Don’t forget, either, the substantial teenage and younger demographic; much of Volume 18 strikes me as essentially a children’s record, an introduction to pop rather than the thing itself, and that in itself is no bad thing.

One might also examine the kind of songs selected for these albums, and it has to be said that even the originals of most of these hits carry within them an inbuilt degree of anonymity; these songs, by and large, could have been sung by anybody – does anyone know what Lobo looks like, without looking up Google Images? The entangled web of individuality and freedom – if that’s not too much of a contradiction – described in “Me And You And A Dog Named Boo” does not carry the personal, as in a life recognisably lived, element inescapable throughout a record such as Carole King’s Tapestry, one of many albums omitted from this tale as a direct result of Top Of The Pops Volume 18, and yet an album which to date has probably and comfortably outsold all 92 volumes of Top Of The Pops combined. On Tapestry a sixties survivor, just wrenched out of a painful divorce and resettled in a new and happier marriage, looks back on what she, and by extension her audience, has been through, what we as a totality have seen, and comes to articulate and spellbinding terms with it; her revisits of “Natural Woman” and “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” are truthful, candid and artistically and emotionally convincing, and her new songs – “It’s Too Late,” “Beautiful,” “Smackwater Jack,” the elastic ecstasy of “I Feel The Earth Move,” and so on – sparkle with a naturalness and communicativeness absent from the deliberately anonymised world of the soundalikes (there is an attempt at “It’s Too Late” on Top Of The Pops Volume 19, which, perhaps happily, will be of no concern here).

But “Co-Co,” “Tom-Tom Turnaround,” even the venerable “Black And White” (the latter is a considerable improvement on the Hot Hits reading, although the handclaps are overmiked, a problem which recurs throughout the album, and the singer unaccountably sounds like Jimmy Somerville in the fadeout) – what are these songs for? Where are their anchors? No offence to Messrs Chinn and Chapman, who at this stage were merely honest, jobbing songwriters looking to earn a living and build a reputation, writing off-the-peg hits for whoever wanted them, but beyond the existence of the song, I can’t connect to “Co-Co” (and neither, ultimately, could The Sweet, hence the necessary eventual move to “Blockbuster” etc.; the version here is more convincing than the Hot Hits one, with an actual steel drum present, albeit little or no bass, and an overpowering bellow of a male backing singer in the choruses). These are inoffensive, jaunty hits which catch the public’s attention for a few weeks and then gradually disappear, leaving little lasting impression (I can’t imagine, for example, that Roy Wood regards “Tonight” as one of his major songs, as opposed to a routine contract-filler to enable him and Jeff Lynne to get on with ELO). Of the “classics,” i.e. those songs associated with specific artists – “Get It On,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Won’t Get Fooled Again” – the approach simply doesn’t work because the original musicians’ personalities are so intensely entwined with the songs that any attempt to cover them note-for-note, gesture-for-gesture, inevitably results in nothing bar a grey Xerox.

But there are other technical issues at work here which inadvertently reveal new layers, and perhaps subtexts, to the Top Of The Pops methodology. In general these recordings are far closer to the originals than Hot Hits but there remains a post-Dunkirk can-do mindset where it is abundantly clear that these are Brits doing their best in reduced circumstances. The inevitable errors consequent to such a short turnaround time pay clear witness to this – the fumbling slide guitar on “Tonight,” the missed guitar glissandi in “Tom-Tom Turnaround,” the leaden rhythm and low voice flatness in “La-La Means I Love You” (although the latter is one of the better and more heartfelt attempts on the record; when given something they can get their teeth and heart into, i.e. Thom Bell’s proto-Philly soul, the musicians noticeably respond).

But, as I suspected with “Zoo De Zoo Zong,” there is another spirit at work here somewhere. Overwhelmingly the most problematic of these dozen tracks is “Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep,” a half-decent song which here is absolutely, and I suspect intentionally, ruined. There is such a determinedly amateurish gait to the performance that I even briefly felt compelled to invoke the spirit of the Shaggs and/or Christian Wolff – two paths towards Escalator, with its insistence on non-professional singers mixing with experienced hands like Jack Bruce and Sheila Jordan – and wondered what a Portsmouth Sinfonia/Scratch Orchestra-type approach to these songs would have produced (or would Cardew, Bryars, Nyman, Eno & Co. have been just too damn knowing for it to work?). Broadly speaking, Barbara Kay sounds as though she’s taking the piss out of the song and Sally Carr’s original vocal, and her fellow musicians appear to agree with her; this is irredeemable crap and both you and we know it – but isn’t that verging on the unforgivably cynical? What does that say about musicians’ attitudes to their audience?

So these songs get liked for a little while, and then more songs come to replace them, and if they’re lucky some will get remembered; this is how most of us respond to and live with music, and there is the question of where the consumer/performer interface gets further eroded to be considered, but there is one more album of this type to consider, and I will reach my conclusion there. I am, however, aware that records such as this come close to undermining the purpose of the “music writer,” with our unavoidable insistence on probity and individuality on the part of artists (even when working as a collective), and raise the question of whether this approach conflicts with or rubs out the greater societal collectivity necessary to stop us from destroying ourselves. I don’t believe that those who bought these albums like music less than those of us who are supposed to know more about music, or that, worse, they don’t like music at all – merely that the way most people’s lives unfold means that they cannot commit all of the time and effort necessary to come to terms with questions such as: why this music or artist and not that one? Do income and social status fatally determine who is to be taken seriously when they say that they love music? Does the fact that I will probably never voluntarily listen to this record again – and yet revisit Tapestry countless times – mean that I am missing something, or does everything have to be more than just the song, or calories, or oxygen, to convert existence into living?