(#521: 18 March 1995, 1 week)

Track listing: No More ‘I Love You’s/Take Me To The River/A Whiter Shade Of Pale/Don’t Let It Bring You Down/Train In Vain/I Can’t Get Next To You/Downtown Lights/Thin Line Between Love And Hate/Waiting In Vain/Something So Right

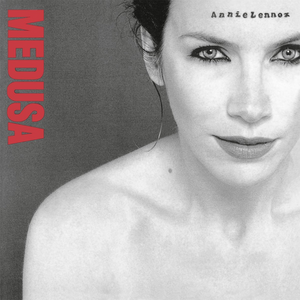

In her brief liner note to this album of upholstered covers, Lennox is at pains to point out the absence of “any particular theme or concept” in her choice of songs to interpret, but that may strike you as disingenuous. I sense a very careful and deliberate architecture to both the choice and the sequencing of these ten songs, where “Train In Vain” gives way to “Waiting In Vain.”

This is not to say that the music here is remotely thrilling or enticing. It sounds professionally glossy – Anne Dudley, Marius de Vries and co. are all opulently present – but centreless. Her “Downtown Lights” is as foreseeable a failure as Tina Turner’s “Unfinished Sympathy” would later prove to be, even though it is probably the one song of these ten which Lennox was absolutely clear about wanting to sing; however, this Aberdonian can’t do Glaswegian, and the song makes no sense if Paul Buchanan isn’t singing it and the music isn’t breathing out from behind, or possibly from within, him. Likewise, despite her protestations about being a Scot attempting to sing Al Green, we should recall that a man born in Dumbarton – David Byrne – took us to a related but entirely different river, which Lennox here simply cannot do.

In parallel similarity, her reharmonising of “I Can’t Get Next To You” is rather ingenious, but dehydrated in comparison with Al Green’s drastic gospel reworking, which draws out the Biblical mythology underlying the song. As for Neil Young, you’d never imagine that this amiable gambol through contemporary societal apocalypse were anything more than Rough Guide tourism.

At times, Medusa does become intriguing. If Mick Jones wrote “Train In Vain” as a rather petulant break-up song about Viv Albertine, Lennox slows it right down and turns its serial, rhetorically negatory “stand by me”s into modestly bloodied, accusatory spite – some ghosts had clearly not been fully exorcised. The Clash original (which was not left off the track listing on the sleeve of London Calling to deter possible punk purist embarrassment, but because the song was only added to the record after the album artwork had gone to the printers – it was originally intended for an free NME flexidisc, which idea, for some long-forgotten reason, fell through) was produced by Guy Stevens, who not only gave Procol Harum their name but was also the primary inspiration for their most famous song.

Ah yes, “A Whiter Shade Of Pale,” that unlikely marriage of Bach and Percy Sledge – one can imagine the group still being The Paramounts, on the stage of some long-abandoned, empty but still neon-lit ballroom, performing “When A Man Loves A Woman” with so much echo on the organ that it sounds like a hymn – which in its time seemingly drifted in from nowhere; the North Sea of the pirate ships which played the record, the Southend-on-Sea from which the band came, the greying coast of Aberdeen where the twelve-year-old Annie Lennox heard it and maybe realised that she had to escape.

And yet, if “A Whiter Shade Of Pale” has a direct descendant (that is, if you do not count the waves which spread across the Atlantic to Jamaica and finally influenced Bob Marley to write “No Woman, No Cry”), it is “Party Fears Two” by the Associates. A deliberately oblique song title and lyric whose only recognisable hook is an instrumental keyboard pattern which sounded like absolutely nothing else at the time and which song appears to be about someone getting drunk, or stoned, at a party and failing miserably to chat up a girl.

But “Whiter Shade” drifted into the world as imperiously as pop’s premier ghost ship, and I find the Top Of The Pops performance of the song intolerably moving, particularly in the current context – look at the audience, and think of the time when we can all dance again:

Lennox’s reading doesn’t amplify any of that mystery (although I would be exceptionally interested to hear her “Party Fears Two”). Perhaps the greatest service that Medusa provides – although, given that the album sold six million copies worldwide, 600,000 of which were sold in Britain, I expect that the Blue Nile were very happy with the royalty cheques – is to make David Freeman and Joseph Hughes, the authors of “No More I Love ‘You’s,” properly recognised. Little wonder that this was Medusa’s lead single, since it is the song to which Lennox sounds most sheerly committed.

Freeman and Hughes recorded the song under the umbrella name of The Lover Speaks. It was inspired by elements of Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse, but their reading sounded rather formal and fidgety next to the breezy naturalness of Martin Fry or Green Gartside. As a Jimmy Iovine-produced single, it received modest critical acclaim and fairly heavy radio play but ended up not being much of a hit, despite being released on two separate occasions. Lennox regarded this as gross neglection and sought to put things right with her reading – she does manage to draw out the realisation that this is not a lament of a song, but rather a polite proclamation of liberation; no more bullshit, no more pretending that something is working when it manifestly isn’t. The song cries, hurrah, I am FREE, and Lennox appends the inevitable exclamation mark successfully.

Her reading of “Thin Line Between Love And Hate” is striking, and sinister, as indeed was the Persuasions’ original with its slow dissolve from suppressed fury disguised as politesse – the “language of love,” if you must – to apocalyptic retribution. Chrissie Hynde took the song one step further and sang it from the perspective of an angrily amused third party. But Lennox performs the song as though she herself is the revenging protagonist, that she is the one who has almost killed this shit of a man – and her improvised additions in the song’s coda are brutal. “C’mon,” she taunts. “C’mon, baby, baby – you don’t give a damn about me…you don’t really care about me.” Rage has boiled over and it is payback time.

This catharsis is succeeded by a strange but logical and rational sense of peace – and, more importantly, the closing song bookends the opening one. “Something So Right,” a song about how some people find it impossible to say the words “I love you,” and how consequently it takes “a little time to get next to me.” It sums up the rest of the album so rationally and benignly, as though to proclaim; the hurt is done, all is now resolved, it’s over it’s over nineties albums of autobiographically-retooled covers by eighties stars no more I know.