Marcello Carlin and Lena Friesen review every UK number one album so that you might want to hear it

Sunday, 3 March 2013

VARIOUS ARTISTS: Disco Daze And Disco Nites

(#247: 4 July 1981, 1 week)

Track listings:

Disco Daze: I Feel Love (Donna Summer)/Contact (Edwin Starr)/And The Beat Goes On (The Whispers)/I Owe You One (Shalamar)/Don’t Push It, Don’t Force It (Leon Haywood)/Bourgie, Bourgie (Gladys Knight and The Pips/One Nation Under A Groove (Funkadelic)/Ain’t Gonna Bump No More (With No Big Fat Woman) (Joe Tex)/Southern Freeez (Freeez)/Rapper’s Delight (Sugarhill Gang)/He’s The Greatest Dancer (Sister Sledge)/Queen Of Clubs (K.C. & The Sunshine Band)/Stuff Like That (Quincy Jones)/Searching (Change)/More, More, More (Andrea True Connection)/Rapp Payback (James Brown)

Disco Nites: Intuition (Linx)/Knock On Wood (Amii Stewart)/Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now (McFadden and Whitehead)/Jump To The Beat (Stacy Lattisaw)/Stomp (Brothers Johnson)/It Makes You Feel Like Dancin’ (Rose Royce)/Funkytown (Lipps Inc.)/Instant Replay (Dan Hartman)/Le Freak (Chic)/(Somebody) Help Me Out (Beggar and Co.)/Ring My Bell (Anita Ward)/Get Down (Gene Chandler)/Lady Marmalade (LaBelle)/Everybody Get Up (UK Players)/Can You Feel The Force (The Real Thing)/December 1963 (Oh, What A Night) (Four Seasons)

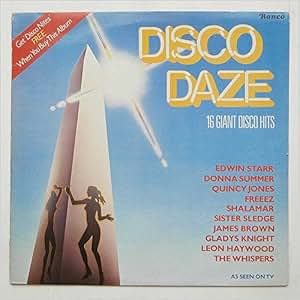

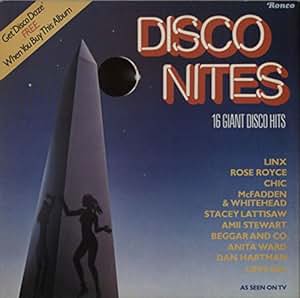

I am aware that many of you are collecting, or downloading, these albums as I go through them. While I do not recommend this as a matter of routine (Stars On 45), it is oddly noble that you might feel inspired to seek the records out, make your own sense from them. Perhaps you may already have looked at the covers of these albums – wait a minute, “albums” as in plural, as in, more than one of them? – shrugged your shoulders and continued to wait for others to come along. You may not get past the minimalist sleeve designs (Acrobat Design Ltd/John Anderson), both of which appear identical – a shadow of a dancer, or vice versa, projecting herself within the Washington Monument, or perhaps a paradigm of the Shard (seen at certain viewpoints across London at the right time of day and with the right weather conditions, the Shard in profile can look awfully like these covers).

If you are of a certain age you may well remember these records being advertised on TV by an excitable Tommy Vance, looking for all the world like it was still 1975, breathlessly instructing viewers to go get them now – buy one, get the other free, all for just £5.49. Or the sleeves themselves with their semi-careless misprints (“Stacey Lattisaw,” “The Stomp”), their near-complete absence of information, and the microscopic warning: “To ensure the highest quality reproduction, the running times of some of the titles as originally released have been changed.”

In actual fact, there is not much interference with the titles as originally released – there’s certainly nothing like the random hacking of verses or early fadeouts that you get on, say, Disco Fever, and to these ears “I Feel Love,” for instance, is present in its five minutes and 55 seconds totality (the same length as “Bohemian Rhapsody” and “I’m Not In Love”; someone ought to write an essay on the importance of nearly but not quite exceeding six minutes). If you want the “full story,” there really is no alternative to finding the 12” mixes of all (or most) of these thirty-two songs.

But you may look at the £5.49 retail price and, if you remember the times, scratch your head and do a double take; hang on, didn’t albums routinely cost £3.49, or £3.79, or £3.99, or at the very worst £4.29, in 1981? And despite the “free” offer, there was no way you could buy Disco Daze and not get Disco Nites; neither record was ever available separately (interestingly, the catalogue numbers suggest an eleventh-hour reversal of priorities; Disco Nites is RTL 2056 A, and Disco Daze RTL 2056 B).

In fact, Ronco were cheerfully conning you into buying a double album at a slight discount. This marketing trope was necessitated by the fact that, by 1981, TV-advertised compilations, though still selling, weren’t quite selling as much as they used to. Ronco itself had not had a number one album in some eight years (the That’ll Be The Day soundtrack). But the buy one/get one free bunco booth schtick worked, and for the next couple of years two-for-one (and a half) became standard practice.

Added to this is…well, a glance at the track listings may startle you, since despite some overlap with previous compilations (notably The Best Disco Album In The World), it really is a strong selection of music. Were this to come out today on Rhino as a fully-annotated 2CD package, with detailed, explanatory sleevenotes by, say, Ady Croasdell or Ian McCann, it would be hailed as a landmark document of its time. As it stands, I do not think the compilation is random; I believe it is telling a story that is highly relevant to the summer of 1981, and to where pop music might reasonably or unreasonably be expected to go from what it proposes. It is as definitive a collection as I think could have been assembled at the time – no Heatwave, or Michael Jackson, or “Mighty Real” or “Shame” but really you could make a third and fourth album out of what could have been added – and with one exception, it is highly listenable, and in many senses is a frighteningly euphoric listen, heard one track after another, accumulating and culminating in…well, in what?

Some kind of way out of “1980”?

The Future Was Already Here

For a time in 1977 it was fashionable, and even desirable, to speak of and revel in the "dehumanisation" of pop. One disco hit from that year, "Welcome To Our World Of Merry Music" by Mass Production, summed up the mood by name and title alone. But there was also Bowie, writhing on the edge of total extinction on side one of Low, and then absenting himself, other than as a ghost, throughout side two; the neutered, encased howls of Iggy on "Nightclubbing," also produced by Bowie; the first wave of instrumental synth hits such as Space's "Magic Fly" and Jean-Michel Jarre's "Oxygene Part IV," both of which seemed free from the touch of any human being (which did not in itself make them bad records; quite the reverse).

But there was also Kraftwerk, to whom I had become attached following an attraction to Can which had been sparked off by an attraction to Mike Oldfield...and Trans-Europe Express mesmerised me as much as, if not more than, any punk record in 1977; they united Bowie and Iggy in a cafe in Dusseldorf, the metal on metal bashing and the troubled serenity of the melody could literally have gone on forever. There is an awesome sadness about the record, but also a balancing wonder. Kraftwerk, then as now, reminded me that even the most "inhuman" of music was unimaginable without the touch of humanity.

And then there was Giorgio Moroder, and his preferred singer Donna Summer. And there was the then-new cult of the extended 12-inch single, to prolong dancers' drug-induced ecstasy on dancefloors; "Love To Love You Baby," a semi-banned top five hit in early '76, sold mainly on the glorious 16 minutes and 47 seconds of its full-length 12-inch incarnation. Summer and Moroder's subsequent work provides a curious parallel to that of their one-time labelmate Scott Walker; the expatriate, slightly lost American reworking American musical memes in densely European ways (the echt-Spector of "Love's Unkind" has the clarity and slight coldness of a European studio). Even Moroder's minimalism was dense; listening to their masterpiece, 1977's double album fairytale Once Upon A Time...Happily Ever After, there are always at least three different basses on the go. That record denies the lie of "inhumanity"; listening to the still-astounding eleven-minute segue of "Now I Need You"/"Working The Midnight Shift," you have to remind yourself that Underworld didn't record this yesterday, and that its emotional essence is about a shattered and abandoned human being long since condemned to existence rather than life (it is an electronic foreshadowing of Leonard Cohen’s “The Guests”).

"I Feel Love" comes at the end of the album I Remember Yesterday, an electro-xerox of the history of 20th century pop, and its sudden surge into the future is as shocking as that of "A Day In The Life" or "Good Vibrations" at the end of their respective albums. The record itself stands at the crossroads of just about everything. The lyrics are pared back and minimal to a degree not witnessed since "Tutti Frutti" - fascination over meaning again - but then the meaning was so unambiguous and precise. Summer sings "Ooohhh, it's so good, it's so good..." and "Ooooohhhh, heaven knows, heaven knows..." with curlicues straight out of Patti Page, or maybe Laura Nyro. The impression is of signifiers of love derived from second-hand knowledge of The History Of Pop, cut up, minimised and encased within an unending and palpable pulse (in fact, the singer of whom Summer reminds me more on this record than anybody else is Smokey Robinson, the only other person I can think of who would have put Picardy thirds to such florid and liberating use within a pop song).

Then we reach the gliding sustenatos of the chorus, which now betrays psychedelia, but instead of guitars-as-sitars there is this unplaceable electronic harmony, not quite mechanical and not quite lubricious (we still get a feeling of 1968, and a reminder that once Summer was in the chorus line of Hair). And then, after the second verse and chorus, Moroder has the unprecedented audacity to fade Summer's voice out altogether, leaving just the metronomic beat and the basic eight-note rotogravure pulse. This was something no one could recall having happened on a pop record before, and...

...it just continues. Synthesisers and additional rhythms in different keys and at different angles and tempi fly in and out of the track, shifting in and out of focus, like transient constellations. It is hypnotic and enticing and entirely alien, and demands a rare degree of micro-listening; to catch all the different little imprints and tones before they vanish, knowing that each changes the basic DNA of the track imperceptibly but irreversibly. In truth the recording was far less complicated; the bass pulse was a four-note riff played in the left channel which immediately echoes half a beat later in the right. But its implications changed the way pop music sounded forever.

Yet this is not a woman lost in the machine; in the Kraftwerkian sense, Summer can be said to be The Woman-Machine here. SAnd there is something of the triumphant as the framework, the mesh, lets Summer back in: "Ooooohhhh, I got you, I got you...I go-ooooo-t youuuuuu..." Some think she is trapped in the Moroder machine, but it is much more apparent that this is Summer singing from the inside of herself; the pulses are the arteries, carrying the blood to facilitate a speed and rush which no drug or machine could provide.

"From here to eternity, that's where she takes me," sang Moroder on his own, equally avant-garde hit single later the same year; and "I Feel Love" takes us into a gorgeously golden future as unapologetically as "God Save The Queen" - the sequencers, the style being the content, the irrefutable and marvellous pulse plugged into our thankfully still beating hearts and minds; it could go on forever (and Patrick Cowley's subsequent fifteen-minute remix seemed intent on testing out that theory) and thereby ensures that pop, and life, and love, and not in that order, can go on forever. And ever. "I Feel Love" is the beginning of this time.

Those Who Would Follow

Edwin Starr’s run of hits had dried up somewhat following his “War” days but he must have seen what was happening, since before the seventies were over he managed to bounce back with a record that pretty much follows exactly in “I Feel Love”’s spacey footsteps. But “Contact” also benefits from the sort of analogue synth squelches one simply doesn’t get these days and a general rhythmic looseness, as well as the paradoxical show tune grandeur of the song itself, and the way in which Starr declaims it, moving between teasing (“You were looking at ME! I was looking at YOU!”) and Rodgers and Hammerstein (“Across the crowded disco room”). Actually the synth wobbles are not so much Clinton and Parliament as they are Manfred Mann’s “Blinded By The Light.” This is not Hi-NRG, but a clear signposting on the road to it.

The Sound Of Los Angeles

Lena, who is from Los Angeles and therefore knows about these things, comments on the very clean sound that Dick Griffey’s Solar Records managed to achieve, highly characteristic of its city. And so we have the Whispers, R&B chart regulars since 1969, who in 1980 suddenly broke through with this breezy blast of euphoria as declaration of principles; a recuperating Green Gartside heard “And The Beat Goes On” and its various coded messages – “There’ll never be an ending,” “I might as well get over the blues” – and knew straightaway that this was the road he now had to travel. The song itself is a “Winner Takes It All” role reversal; the sung-to subject has been dumped and is in the dumps, but is gently being prodded to move forward.

Meanwhile, at more or less the same time, Shalamar – in 1980 still two years away from their big British/New Pop breakthrough – came through with the superb “I Owe You One” with Howard Hewett and Jody Watley’s committed vocals, busy percussion and a grand sense of musical architecture; the swelling crescendo that roars up over the bridge and Hewett’s “What you DID for ME!”

The Old Guard Finds A Way

Leon Haywood, from Houston, was by 1980 an R&B veteran of sorts, but “Don’t Push It” was his big British hit; more serenely funky than much of what surrounded it at the time, with an opening horn fanfare which sounds like it might have been Chicago. Its subtle onward push was later reflected in such hits as David Christie’s “Follow Up” (an early manifestation of French disco).

Gladys and the Pips seemed rejuvenated on CBS, and working with Ashford and Simpson, and their “Bourgie, Bourgie” – a song so good a Glasgow indie-soul group named itself after it (if Paul Quinn’s out there, I hope you’re doing OK) – is as comprehensive a demolition job on the affluent status quo as anything that their labelmates The Clash had to offer – get that tambourine, Knight’s searing, accustatory “I know they LIKE it like THAT!” and the general prophecy (the “bourgeois”/”boulevard” crossover) that future labelmate Chuck D will expand almost a decade hence (the moment Ice Cube intones the words “As I walk down Hollywood Boulevard” over twenty disintegrating orchestras and firebombs on “Burn Hollywood Burn” from Public Enemy’s Music From A Black Planet is one of the most numbingly terrifying yet exhilarating moments in all of popular music; this is its template).

Then Funkadelic themselves return, to rebuild a country in a more placid, yet no less thrilling, manner. Joe Tex’s novelty hit I will leave to Lena to analyse.

The Weather’s Different In Britain

There was this thing called Britfunk, which ran in rough parallel with New Pop, and it provides the only three tracks on either record from 1981 (as well as two others). Two of these I will leave until later in the story, but in case you are bewildered by the UK Players, they appear to have been a sort of collective John the Baptist of Britfunk (or one of them anyway, since Hi-Tension are not represented). Like Heatwave, they toured expatriate army bases in Germany, and “Everybody Get Up” was their moment; it does seem to prefigure most of what came after it, with a keyboard player audibly eager to be Herbie Hancock and a singer who sounds, startlingly, like George Michael (yes, I know, it should be vice versa). Listening to it now, it is even more of a prophecy.

But by the summer of ’81 both “Intuition” and “Southern Freeez” had been top ten hits here. Linx were a terrific duo – a slightly less etiolated Level 42, with similar everyday lyrical concerns; like the latter’s later “Running In The Family,” “Intuition” is an account of Just William-like childhood memories – it is the slapstick B-side to “Mama Used To Say” – with an admirably cool vocal from David Grant (never to be bettered in his subsequent careers as solo artist, vocal coach and reality TV judge) and an insane arrangement (whatever happened to producer Bob Carter?) incorporating steel drums, Spanish guitar, slide whistle, an increasingly rhetorical drumkit, and Chris Hunter’s soprano sax (their Intuition album is a mandatory purchase).

“Southern Freeez,” however, is a far more sombre matter. It begins with subtle backward keyboard loops, a pronounced rock guitar and a production which is of a markedly different, greyer and more claustrophobic air than the American records collected here. Ingrid Mansfield Allman's lead vocal is slyly androgynous, but the real moment of startlement is the instrumental break, where bass and keyboards get ambiguously busy in a manner that directly recalls A Certain Ratio (“Winter Hill” for example; the classic “Waterline” and “Knife Slits Water” in the longer term) before a blinding drone of synthesiser leads us back to the song. Hovering, disturbing; Lena reckons it sounds like a speeded-up Massive Attack.

Chic Cheers

“Le Freak” and “He’s The Greatest Dancer” have been here before and are as unimpeachable as ever. “Le Freak” in this context sounds like nothing less than Rodgers and Edwards’ “’Antmusic’” with the same bubbling undercurrent of anger; witness the contempt with which the lines “Come on down and have a real good time” are sung (they’ll sing about “54,” but “54” won’t ever let them in).

And of course “Good Times” inspired “Rapper’s Delight,” the “Rock Around The Clock” of its age, a record which, though less obviously radical than “I Feel Love,” will go on to have at least an equal impact. Of course, here we get the standard radio edit rather than the full fifteen-minute glory, but it’s still enough to let you know how fun and new this rap thing once was. As it made #2 on the NME and Radio Luxembourg lists, it will again be down to Lena to give the record the comprehensive accolade it deserves, but it’s sufficient here to speak of how it gradually opens out to talk about “super sperm,” dodgy chickens, ladies and parties, “Guess what, America, WE LOVE YOU!” before culminating in a freestyle collective improvisation, and how, as with “One Nation Under A Groove,” Obama was still a teenager when it happened.

Miami Advice

“Queen Of Clubs” and “Ring My Bell” bookend the story of TK and the Miami Sound (although in reality the latter extends far beyond both, and in both directions). The former is by far the oldest record here, from 1974, and although it did not reach the US Top 40 it was K.C.’s first UK hit. Consequently it sounds a little left over from the sixties; Harry Casey’s vocal testifies, while the chorus and horn arrangements could have come off a sixties Stax revue. But there is the ghostly high cry (George McCrae?) that materialises with each chorus, and the percussion becomes increasingly animated, thus setting a path for the future.

But although Chic ruled the dance world, and most of the pop world, in 1979, the Miami Sound still had a few unexpected tricks up its sleeve. "Ring My Bell" was written by veteran soulster Frederick Knight ("I’ve Been Lonely For So Long"), produced by TK Records veteran Henry Stone and sung by Ward with an excitable, tremulous and rapid quiver recalling a newly sexed-up Deniece Williams.

There are few disco records so unqualifiably happy, and fewer still which bounce with such pre-coital elan. "Ring My Bell" doubles as one of the great "Hi honey I’m home!" pop records, and its musical elements – the cooing syndrum, the busy clicks of pots and pans – give the record an air of a Max Fleischer cartoon where the entire kitchen suddenly becomes as animated as Anita, or more so, all dancing with joy and expectation as he comes back from a lousy day at the office. "I’m glad you’re home," grins Ward, before winking the rhetorical question "Well, did you really miss me? I guess you did by the look in your eye." They’re both up for it. "Well lay back and relax while I put away the dishes/Then you and me can…rockabye." That last "word" is sung as though swallowed back into the singer’s lips, to give her all the more fuel with which to kiss.

The chorus is sung with a dazed highness; everything seems to be bending and moistening, including the awed sighs of the backing singers and that half-human, half-machine syndrum which oodles and shimmers because it just can’t wait. The patient glockenspiel is the record’s one discreet acknowledgement to the Chic Organisation ("I Want Your Love"). After one more verse savouring the night as being "young and full of possibilities" and a couple more choruses, Ward disappears into the record’s fabric – getting down with it, so to speak – while the record continues to bubble excitedly, like lubricious, recently-oiled bedsprings. "Ring My Bell"’s primary coloured candy-dada not only foresees the imminent antics of Ze Records – complete with heavily inverted comma “Oooooooh!”s and “Aaaaaaaaahhhhhh!”s from the backing singers - but with its mechanical "chick-a-chick-a" growls even anticipates Timbaland.

Quincy Jones

“Stuff Like That” – another Ashford and Simpson song – is helped by the great notion of collectivism that comes with all of Jones’ productions; crucially, the producer leaves plenty of space in his work for his collaborators to make their mark on the song. So Chaka Khan’s uncredited lead vocal is knowing and welcoming, the relationship between electric piano and tick-tick drums uncanny, and there is a moment, where Ernie Watts’ saxophone floats in above opulent string synthesiser, which makes me realise where Chas Jankel would have got the idea for the middle section of “Reasons To Be Cheerful, Part 3” (Jones would, in 1981, obligingly cover Jankel’s “Ai No Corrida” as a kind of mute acknowledgement).

Jones’ spaciousness also works wonders with the Brothers Johnson, and with “Stomp” we finally get to the great Rod Temperton. Clearly this music comes from a jazz, rather than a rock, root, and the squiggly synth solo – the solo on Jackson’s “Rock With You” made more specific – betrays a rather wonderful lightness to what in lesser hands might have been disco Slade. “Short ones standing tall”; isn’t that what, or whom, the days of disco were always about?

France

Change did “Searching” and schaffel dance rose to the surface. An uncredited Luther Vandross has great fun with his crowded disco room (“I don’t want romance, I just want a CHANCE!”) while the riff rolls along like the bluest of Niles (an appropriate comparison, since Billy Ocean’s “When The Going Gets Tough, The Tough Get Going,” which I’d say owes a lot to this, came along just over half a decade later, although the saxophone solo here is better, because less decisive).

It really is as if the future of music is being methodically laid out before our eyes.

Funkin’ For Jamaica

“More, More, More,” back from Soul Motion, sounding more dubby and Jamaican than ever.

Back To The Beginning, Part One

It helps that he namechecks Master Gee of the Sugarhill Gang, rather enthusiastically, at the beginning.

It is also enormously helpful that, after nearly twenty-five years, Then Play Long is now able to introduce James Brown, a performer who started having hits around the time Songs For Swingin’ Lovers was released. And there is something deeply poignant about this brief survey dovetailing back at its (first) end towards the person without whom the rest of the record arguably would not have happened. JB was back, and still anxious to let the world know he knew what time it was.

“Rapp Payback” was a thrilling comeback, an end-of-year-list single of 1981, a year in which great singles ran easily into triple, if not quadruple, figures; even in this exalted company, the Godfather excels, sounding his freshest and most eager in a decade, as though the original, gruelling Payback double album was just a painful memory awaiting erasure. “Hit ME!” he barks (Ian Dury again) before going through all the old tricks, including “Sex Machine” and even "Roll Over Beethoven." What did he say there? “Way back down in Birming-HAM”? Does it matter? The horns sound as out there as anything James Chance and the Contortions could cook up, and Brown’s own vocal verges on the unhinged, but joyously so. The song, like disco itself, could easily go on forever. And ever.

Hair Revisited

Schaffel dance? Well, there was Amii Stewart, like Donna Summer a refugee from that musical, ready to drag Stax into the 21st century. As good and powerful as it was the last time I wrote about it, and her one clear moment.

Philadelphia

“Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now” was the last great Philly hit (though some could justifiably argue for “Nights Over Egypt,” “Life On Mars” etc.) and an awesome demonstration of proudly stubborn defiance, where all the lessons of “Wake Up Everybody” and “Let’s Clean Up The Ghetto” have been learned and absorbed, and the singing gives way to nothing and nobody (“Gonna polish up our act,” “Don’t you let NO-THING, NO-THING, STAND IN YOUR WAY!,” “EVERY WORD I SAY!,” “We’re on the move”). TRY to move us, fuckers.

Dancing in the streets, these glorious days of disco and Democrat government, 1977-80, and Obama is still only a teenager.

Because these songs, when heard in a line like this, do convey a certain poignancy, a lifestyle, a world, about to be swept away by Reaganomics and Reaganpop. An age of gold.

Washington

Narada Michael Walden masterminded “Jump To The Beat” and Washington DC youngster Stacy rides the song’s rhythms with all the willing and determination of the Madonna and Whitney to come; the song is very Chic-like (down to the bass solo; see also “Le Freak,” whose atoms radiate to all of Britain throughout ’79-81) but anticipates both “Into The Groove” and the early (sometimes Walden-assisted) bubblegum pop-soul of Houston. Lattisaw, probably wisely, then turned to the Lord and went gospel, which she sings to this day (her growl of “COME ON!” after the line “Embrace the good things in life,” probably anticipates this move).

Whitfield

Possibly sounding even stranger than it did when I wrote about Rose Royce. All those noises coming out of every corner, like the future.

The Future Is Here Yesterday

Yes, we know what’s happening and who’s coming. But in the meantime, an electro-beat and a treated vocal that could be Daft Punk: “Gotta make a move to a town that’s right for me.” Not a lot needs to be said after that; hysterically soulful, yet minimalist, female vocals, a Chic string line, vocoderised funk – Lipps Inc. didn’t do much after this but didn’t really need to; it is, again, a manifesto, a route of escape from the confining conflagration that so many of the 1980 albums seemed to welcome, let alone anticipate (“Funkytown” was in the same charts as “Breathing”).

It appears to say: there is a way OUT of all this. Out of your constrictions.

Edgar Winter Group

From which came Dan Hartman, and “Instant Replay” could almost be any average slice of late seventies AoR – Andrew Gold, perhaps? – but vamped up here into what can really only be termed disco ecstasy. He scats with the saxophone solo. He is all over the joint. He can’t stop himself, nor do we want him to.

The British Crossover

I said I was leaving two of the Britfunk songs until later, and “(Somebody) Help Me Out,” in the charts at the same time as “Once In A Lifetime,” is, even in this company, akin to the Sex Pistols erupting. A furiously compressed production with football chants – there is Spandau Ballet involvement – this takes the meditations of Beggar and Co.’s alter egos, Light of the World and Incognito, and kicks them into desperate nowness (for some missing connections, check out, if you can find it, the 1982 Phonogram compilation Dura-Dance - it was a cross-promotion job with Duracell batteries and was mixed and designed to be played on Walkmen – which includes, among many classics, Light of the World’s immortal, eleven-minute-long “Time”).

For if this whole album has been a warm-up for New Pop – as I think is fairly obvious from the evidence – then “(Somebody) Help Me Out” is where the crossover happens. Mass vocals are shouted rather than sung, the music funks furiously – Camelle Hinds’ bass almost goes off the scale – and the song is clearly angry and New Pop, in that it is an anti-Thatcher blast. “Don’t put me down,” “It hurts deep inside/To know that you think of me/As a waste of time.” At a time when some of south London was already burning, this was incendiary stuff, as Kenny “Canute” Wellington’s fire alarm trumpet solo makes clear, and not a little threatening. The song eventually retreats into menacing quietude, with dissociated electric piano, wayward drumming and more and more distantly-echoed voices.

The Duke Is Back

Seventeen years after “Duke Of Earl,” he was back, smiling and seemingly unchanged, with a song whose general rhythmic undertow and suggestive lyric (“You’re looking real good in your halter top,” “Shift it in third gear, mama”) make “Get Down” the unacknowledged ancestor of Flo Rida’s “Low.” All done with great charm and ebullience, of course (who else would have thought of “baby bubba”?).

Voodoo Rage

I understand that some people are so bored at the perceived overexposure of “Lady Marmalade” that they might never want to listen to the record, or the song, again. I often wonder whether its persistent replaying on British radio assuages a generational guilt, penance for only placing the song at #17 in our 1975 charts. Like several other notable underperforming singles of that year, there is maybe the impression that “Lady Marmalade” was too good for our charts, that our Top 40 was not worthy of housing it.

Or maybe it’s the dual British disease of guilt and embarrassment that stopped us embracing this violently sexy and sensual record with the abandon it deserved. Even now, it lopes out of its surroundings with a sneery, triumphant defiance that says: “match me.” Everything about it – Allen Toussaint’s woodchopping production, the tangible urgency that arises from the musicians (the horn section break has this album’s second best use of the Picardy third), and especially the electrifying “an electric fox just jumped out of my jacket” vocal performance of Patti LaBelle – has a rawness, a directness, that connects in ways not yet straitjacketed into code words for bad pub kitchens in London, when “soul” was not yet a mallet to be hammered into the heads of people, to teach them alleged better ways of living.

It’s just that “Lady Marmalade” in its determinate bilingual potency addresses the issue of fucking in ways that were really beyond mainstream 1975 Britain. Most of its peers from that year did better in the States, and the artists went on Soul Train first, Top Of The Pops second, or, more frequently, not at all. The record is far less malleable than entry-level tat like “Foe-Dee-O-Dee” or “Baby I Love You, OK.” It sounds alive, stringent and pan-embracing. People still dance to it to forget, or remember, or do penance.

The Real Point Of It All

It was a tremendous comeback. Thirty seconds of electronic abstraction and space effects – what is this, Herbie Hancock’s Sextant? No, it was the Real Thing, and “Can You Feel The Force,” and what a remarkable record it still is, placing them a long way away from “You To Me Are Everything.” Eddie Amoo and his companions sing with an emotional fire that hadn’t been heard in almost two years.

Yet there is more to the record than that, and even more to its penultimate placing on this album. It is, remember, July 1981; New Pop is about to go overground, into the mainstream, and here is both a declaration of how things are going to be, and a final rebuttal of all the glum doom into which even the better albums of 1980 had led us. The aim becomes clear: “I can feel a new beginning everywhere,” the Toxteth diphthongs at the end of the line: “You can see a change in people’s attitudes,” and it is as if pop is coming to life again. Put this collection together with No Sleep ‘Til Hammersmith and Kings Of The Wild Frontier, and suddenly the machinations of Star Sound seem a long way away, discarded and irrelevant. The impression is one of a new society coming into being, a fresh start; away with the apocalypse for there is still far too much work to do. Far from being a random collection of vaguely dance-based hits, this acts as a gauntlet, thrown down in the face of its predecessors, daring them to surpass it.

Many key operatives in New Pop will have bought this album and studied it with meticulous care.

All In All Is All We Are: Back To The Beginning, Part 2

Looked at this way, there is something intolerably moving about the final track being given over to the Four Seasons; a direct connection to the past which fed it and made the record possible. In the video for “December 1963,” singing drummer Gerry Polci enthusiastically gets into the song, while Frankie Valli sits, emphatically slapping his legs to the beat, waiting to come in on the bridge. Interspersed with the performance is monochrome footage of the group as they were, in 1963, and the whole thing suggests a very important sense of continuity, that everything we once promised in New Jersey will come to fruition, if you look easily enough and don’t kill yourself waiting for miracles to occur. It fits in as the perfect coda to this examination of disco and says that – well, remember how sorrowful a lot of people actually were in December 1963 and how so many thought that it was all over, nothing else could be done? The movement, the music, never ends; so it is a shadow of a dancer you see on these covers, or the magnification of a soul, and so we can pick ourselves up and get moving again. Such was the message of the record that was at number one in the album chart the week of my father’s fiftieth, and final, birthday.