Marcello Carlin and Lena Friesen review every UK number one album so that you might want to hear it

Sunday, 21 December 2008

Freddy CANNON: The Explosive Freddy Cannon

(#18: 12 March 1960, 1 week)

Track listing: Boston (My Home Town)/Kansas City/Sweet Georgia Brown/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/St Louis Blues/Indiana/Chattanoogie Shoe Shine Boy/Deep In The Heart Of Texas/California, Here I Come/Okefenokee/Carolina In The Morning/Tallahassee Lassie

When Freddy Cannon suddenly surfaces in the middle of 1974’s Disco Tex and His Sex-O-Lettes Review album to sing the rather outrageous “Outrageous” it sounds entirely logical and he sounds, suddenly, entirely of his time, suggesting that at his peak he was some way ahead of his time. But of course one of the masterminds behind Disco Tex was Bob Crewe, the same man who signed up Freddy Cannon back in 1958 and, along with his splendidly named colleague of the time Frank C Slay Jr, produced his run of hits.

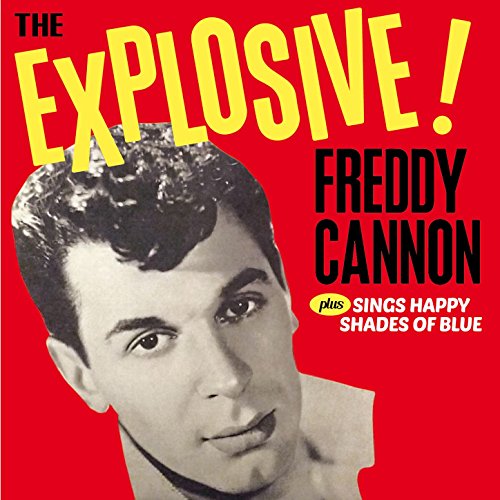

The Explosive Freddy Cannon now seems more and more like a mirage of a blast into the still relatively sedate atmosphere of the 1960 album chart. Rudely barging in to disrupt South Pacific’s seamless run at the top for just one week – although it should be noted that it was number one in the first Record Retailer chart, and maybe its compilers were determined to show some element of difference, even though South Pacific cruised back to number one the following week for a further five-month residence – everything about the record screams “different”; it was the only number one album for the Top Rank label, its red-fading-to-orange cover blown apart by luridly large lettering and a monochrome portrait of the artist seemingly cut and paste into the bottom left hand corner a complete contrast to the opulence of the South Pacific package. And it was the only hit album Cannon ever had in Britain, although its success can be ascribed to the fact that he was actually in Britain at the time, touring widely, turning up on TV and radio to promote both his “Way Down Yonder In New Orleans” hit single and its parent album – and the tactic clearly worked.

Naturally, as can be evinced from the sleevenote, penned by Billboard’s Howard Cook, some bets were still being hedged: “The album may well revive nostalgic memories for adult buyers, and younger buyers will find the treatments of all the material exactly in line with their own contemporary tastes,” and Cook was careful to stress Cannon’s Al Jolson influences (“who always exuded a great deal of dynamic charm – even on his ballads,” not that there is anything remotely resembling a ballad to be found here) rather more than his Chuck Berry ones.

But despite Cook’s sterling attempts to lure in the mainstream album buyers (“It’s a perfect set for light listening and, of course, for dancing”), The Explosive Freddy Cannon comes on like a punk Come Fly With Me. His first hit, 1959’s “Tallahassee Lassie,” with its oozing bends of nascent sensuality (“She’s got a hi-fi chassis!” Cannon excitedly screeches, and he comes out of the song with wickedly winking sliding scales of pleas of “C’monnnnnn honey! Come ooooooonnnnnn BAY-bee!!”), was followed by “Okefenokee” and “Way Down Yonder In New Orleans” and, as you can discern from the track titles, Crewe and Slay worked out the album’s theme fairly straightforwardly.

Mostly the songs follow the grandiose rawness of the “Way Down Yonder” formula; a UK #3 hit single, its New Orleans is markedly less scrubbed than that of King Creole, and much of Cannon’s work does arise as a direct descendent of Dave Bartholomew and Fats Domino (see the horn lines on Cannon’s “Kansas City” for definitive proof) but also works as a parallel to what producers like Allen Toussaint were doing with artists like Ernie K-Doe at the same time. With Cannon, the horn section is effectively dominant; with one startling exception on this album, guitars are virtually non-existent – and, as Dexy’s would do twenty years later, the horns become the “guitar.” This is supplemented by excitable, high register piano and regular rhetorical bass drum hammering whenever Cannon brings a song to the crossroads, and propelled forward by Cannon’s trademark growls and whoops. When set in contrast against his supposed peers – the sundry Bobbys of that timid, brushed whiteboy world – Cannon can come across as the antidote, and frequently he reminds me of someone else of significance yet to come.

“Way Down Yonder” continues to be a wonder; Cannon lunges at “HAH-in the Garden of Eeeee-DEN!” as though both apple and snake, piano cascades in downward ecstasy as he proclaims “Here is heaven right here on Earth!,” the horns trundling up hill and down dale like merry Christmas cable cars (somehow both recalling Domino and foretelling the Bonzos!). His “WHOO!”s seem to squeal freedom and release – given what Crewe went on to do later that decade, Cannon comes across as Frankie Valli’s duende double. Incidentally, the author of “Way Down Yonder,” one Turner Layton, who wrote the song in 1915, was tracked down at the time and found to be alive, well and enjoying his retirement in the unlikely surroundings of Maida Vale, though admitted that Cannon’s concept of the song was somewhat different to the one he had originally imagined (and Layton proved to be a remarkably durable fellow, living on until 1978).

Cannon was a Bostonian, and so Crewe and Slay wrote “Boston (My Home Town)” as an album opener. Beginning with an acappella horn phrase that manages to predicate both ska and Michael Nyman, Cannon then roars into view: “Holy smokes, yeah, it’s the hub!” which might still be one of the best opening lines of any number one album. “Keen town, Bean Town , that’s the rub!” He grasps the song and flings it around with unalloyed glee like a luminous yo-yo. “Pretty girls everywhere USA !” he shrieks (hello Ramones?). He’s going to love her “all the way from Bunker to Beacon Hill” and even drops in a reference to we-know-what - “We’re gonna have a party, Boston tea/Overboard – yeah, in love, that’s me!” – before launching into a cheerleader chant of “M-A-Double S” etc.

The songs were randomly grabbed from American popular music’s history, and while some work more than others – “California, Here I Come” is chiefly notable for the pianist starting to go mildly freeform at fadeout, “Carolina In The Morning” borrows its horn line from Ray Martin’s “Blue Tango” – the overall effect is exhilarating. “Sweet Georgia Brown” is made to work by Cannon’s determined ebullience and a marvellously maximalist, inventive horn chart, and his “St Louis Blues” is as near to punk as anyone dared take the song, right from its staccato, dissonant horn intro through Cannon’s improbably chirpy “I hate to see that evening sun go down” – and then into his startling bored whine of “Yes I’m feeling tomorrow just like I feel today” which suddenly seems to sum up why so many revolutions that will happen have to happen. He sneers his octave-leaping “Or ELSE she WOULDN’T have GONE so FAR from ME!” as though hurdles do not exist, just before the band suddenly goes into a forlorn tango. His “ Indiana ” is a 102-second rave-up punctuated by steamship baritone sax honks.

His “Chattanoogie Shoe Shine Boy” functions as a midway point between the Andrews Sisters and Labelle (whom Crewe would also go on to produce and write for) with its remarkably prescient cries of “hippity-hoppity hoppity-hippity hip hop hop!” and Cannon’s exhortations to the horns, “Oh DO IT DO IT DO IT DOITDOIT!!!” as they blow the filthiest lines they can stir up. “Deep In The Heart Of Texas” foresees Duane Eddy’s 1962 reading with its echoing bass intro – though where did the Palm Court dance orchestra, which inexplicably (always the best way) turns up halfway through the song, come from?

But “Okefenokee” ties all the threads together and reminds me of whom Cannon reminds me of – here, guitars are snarlingly prominent, and then there are those slightly out-of-synch handclaps, those odd chants, Cannon’s intermittent eruptions (“It’s wilder than a ro-DAY-o!”), fearsomely close-miked bass drum, a genuinely brutal and explosive guitar solo (was this really recorded in 1959?), the backing singers’ demented “Whoo!”s…Cannon resorts to ad libbing to take the song out – “Let’s OUT of here, baby!” “Oh sugar! Pleeeeeease baby!,” and as the one-note high staccato piano note takes centre stage it all becomes abundantly clear; this is the father of “I Wanna Be Your Dog” and Freddy Cannon’s screeches, moans, licking of lips, whoops and general overgrown teenage misfit petulance are inventing Iggy. And so the first number one album of the sixties forms a perfect bookend to the last.