(#338: 22 November

1986, 2 weeks)

Track listing: I’ve

Been Losing You (a-ha)/Walk Like An Egyptian (The Bangles)/Heartbeat (Don

Johnson)/Wonderland (Paul Young)/World Shut Your Mouth (Julian Cope)/The Way It

Is (Bruce Hornsby and The Range)/What’s The Colour Of Money (Hollywood

Beyond)/Each Time You Break My Heart (Nick Kamen)/You Can Call Me Al (Paul

Simon)/Thorn In My Side (Eurythmics)/Always The Sun (The Stranglers)/Don’t Get

Me Wrong (The Pretenders)/Rain Or Shine (Five Star)/Brand New Lover (Dead Or Alive)/Roses

(Haywoode)/Straight To The Heart (The Real Thing)/True Colors (Cyndi

Lauper)/You’re Everything To Me (Boris Gardner)/Every Beat Of My Heart (Rod

Stewart)/Glory Of Love (Peter Cetera)/A Different Corner (George

Michael)/Because I Love You (Shakin’ Stevens)/The Greatest Love Of All (Whitney

Houston)/Love Will Conquer All (Lionel Richie)/For America (Red Box)/Heartbreak

Beat (The Psychedelic Furs)/Anotherloverholenyohead (Prince and The

Revolution)/Infected (The The)/Rage Hard (Frankie Goes To Hollywood)/Rock ‘N’

Roll Mercenaries (Meat Loaf and John Parr)/Fight For Ourselves (Spandau

Ballet)/Addicted To Love (Robert Palmer)

By 1986, a truce, of sorts, seemed to have been reached

between the Now and Hits series; just one release each for

much of the year, neither of which coincided with the other (Hits 4, Now 7), with Hits 5

released two weeks in advance of Now 8

for Christmas. That it stayed on top for two weeks perhaps indicates who was

still really ahead in this race, but I wonder whether too great a rush was made

to get the record out; just one of its thirty-two songs made number one, with

another five failing to make the Top 40 at all (one of which, “Heartbreak

Beat,” did not even break the Top 75), and it’s the usual curious mix of

intermittently terrific stuff with an ocean of treacly dreariness. Yet again,

the charts of late 1986 at times had to struggle to keep up with itself, so

rapid were the changes taking place, but here I sense a last-ditch, and

possibly forlorn, attempt to make the old stuff still matter.

a-ha

A fantastic start, and one of the Norwegians’ best, with a

song and arrangement which at different, and occasionally simultaneous, times

suggest the Teardrop Explodes, Roxy Music, Laurie Anderson and even Nick Cave,

since this is the tearing-himself-apart soliloquy of somebody who has just

killed someone, possibly the person to whom he is singing, in the rain; he puts

his gun down on the bedside table and can’t entertain the notion that he could

be capable of this. The music rises, dips and challenges; by the time Morten

reaches the beyond-exasperated scream of “PREYING” in the couplet “Thoughts to

wreck me/Preying on my mind,” he is finished; at one point the song makes as

though it’s going to end, before quietly and menacingly restarting. “How can I

stop now?” asks Morten, in the full and horrific realisation that he can’t.

The Bangles

Did “Walk Like An Egyptian” really become an unofficial Arab

Spring anthem? Its balance of whistling girl-group bubblegum and noisy gong and

guitar dissonances sounded sufficient to spur any revolution. There may also be

an irony in the Bangles’ best-known songs all having been written by men. But

Liam Sternberg had first offered the song to Toni Basil, who turned it down;

three of the group take turns to sing the verses, but producer David Kahne

didn’t like any of Debbi Peterson’s lead vocals, so relegated her to back-up

and furthermore replaced her drums with a drum machine. The wonder is that they

didn’t throw the guy out of a twenty-fifth storey window.

Don Johnson

Written by industry pros Eric Kaz and Wendy Waldman,

“Heartbeat” dates from an age where famous actors were inexplicably also called

upon to sing. Crockett mostly roars rather than sings the song, in a below par

Bryan Adams fashion (the line “I’ve been standing by the fire” being delivered

as though making immediate and unexpected contact with a red-hot poker). Its

typical skyscraper-skateboarding drum fills, guitar squeals and DX7 blasts

cannot quite mask a degree of sweaty straining on Johnson’s past. Only #46 in

Britain, but a top five smash in the States (Hits 5 would probably have done much better in the USA, since many

of its songs were far bigger hits there than in the UK).

Paul Young

“I see you in a dress of blue/With a question in your hand/I

see you in your attitude/Of sorrow and demand” – another Thatcher analogy?

Alas, Young now sounded lost; it is frequently impossible to hear him clearly

through the production fog, and the song, which at times tries hard not to be

Smokey Robinson’s “My Girl,” is not really up to anything. For many 1983-5

stars, the late season of 1986 was to provide some unwelcome shocks; suddenly

the likes of Howard Jones, Ultravox and Young were finding things very hard

going. Passing fashions? In part, but substandard material was also to blame.

Copey

The Belated Entry of the Crucial Three Into Then Play Long, Part 2of 3. What’s left

to say about Julian Cope? Musician, songwriter, psychedelic metal warrior,

activist, psychogeographer, noted archaeologist and historian, accredited

expert on the rock music of Germany and Japan, Head Heritage founder, acidly smart autobiographer and, most

recently, acclaimed crime writer. This suggests either a versatile and

inquisitive mind whose interests and energies are tireless and inspiring, or a

restless and unfocused spirit, unable to stick at one thing for more than five

minutes.

On balance I’d go with the former. I loved the Teardrop

Explodes, me. Wonderful WTF bubble-organ McGoohan-delia, they were. I played Kilimanjaro without end in my first year

at university – and realised I had a lot of work to do when a neighbouring

student asked me whether “Treason” was Duran Duran. “Ah, it’s all the same to

me,” he grinned. Wilder was a

bleared, BLURred November ’81 spike of rosy dreaming which made that month and

my endurance of it worthwhile. I wore my father’s old RAF coat with suitably

psychedelic scarf, and at the time I still had enough hair to let it grow to a

reasonable facsimile of the Cope crop. All that and he had an alter ego (Kevin

Stapleton) who brought Scott Walker (Emmett Hayes) back from charity shop

wilderness into the centre of something.

I stuck with him right through his first two solo albums and

was pleased to see him back on TV in late ’86 belting out “World Shut Your

Mouth” from his customised mike-stand-cum-stepladder.

After two records of Barrett quiescence he reckoned he’d earned the right to do

a third album of scuzzy garage rockouts, and that was Saint Julian. “World Shut Your Mouth” was and is a great “Louie

Louie” ripoff with Cope just wanting everybody to pay attention to things worth

paying attention to. Better on the album where it never seems to end.

I’ve stuck with him up to Brain Donor as well.

Bruce Hornsby

Ben Folds was just about turning twenty when piano-toting

Hornsby, from Williamsburg, Virginia, crept onto the scene with his melancholy

“The Way It Is”; as with “Boys Of Summer,” an abject reminder of how the

ideals, if ideals there were, of the sixties were impolitely being scored out.

“Some things will never change,” sang Hornsby, but nobody listened to the

counterpunch of “AH, BUT DON’T YOU BELIEVE THEM.” Best heard as the background

to Mancunian rapper MC Buzz B’s profoundly moving “Never Change.”

Hollywood Beyond

Remember when Mark Rogers was the future of pop? True, it

was one week in late summer when Melody

Maker was a bit stuck, but this fusion of Squeeze’s “Take Me I’m Yours” and

Irish jig is still quite striking, even though, with the repeated “Don’t tell

me that you think it’s green/Me, I know it’s red,” Rogers argues his point more

often than he strictly needs to do. An album followed, but not in Britain, and

Christ knows what became of him.

Nick Kamen

She’s there, of course, co-writing and producing, and

crooning in the background – as if her trademark “Look in your eyes” scarf

weren’t a big enough clue. But if Madonna now considered herself too good to go

on compilation albums, there was still room for her cast-offs; male model Kamen

can’t really sing and does his best with painfully thin material. Meanwhile, an

exasperated Sean Penn wonders whether he’s supposed to be the eighties’

giraffe.

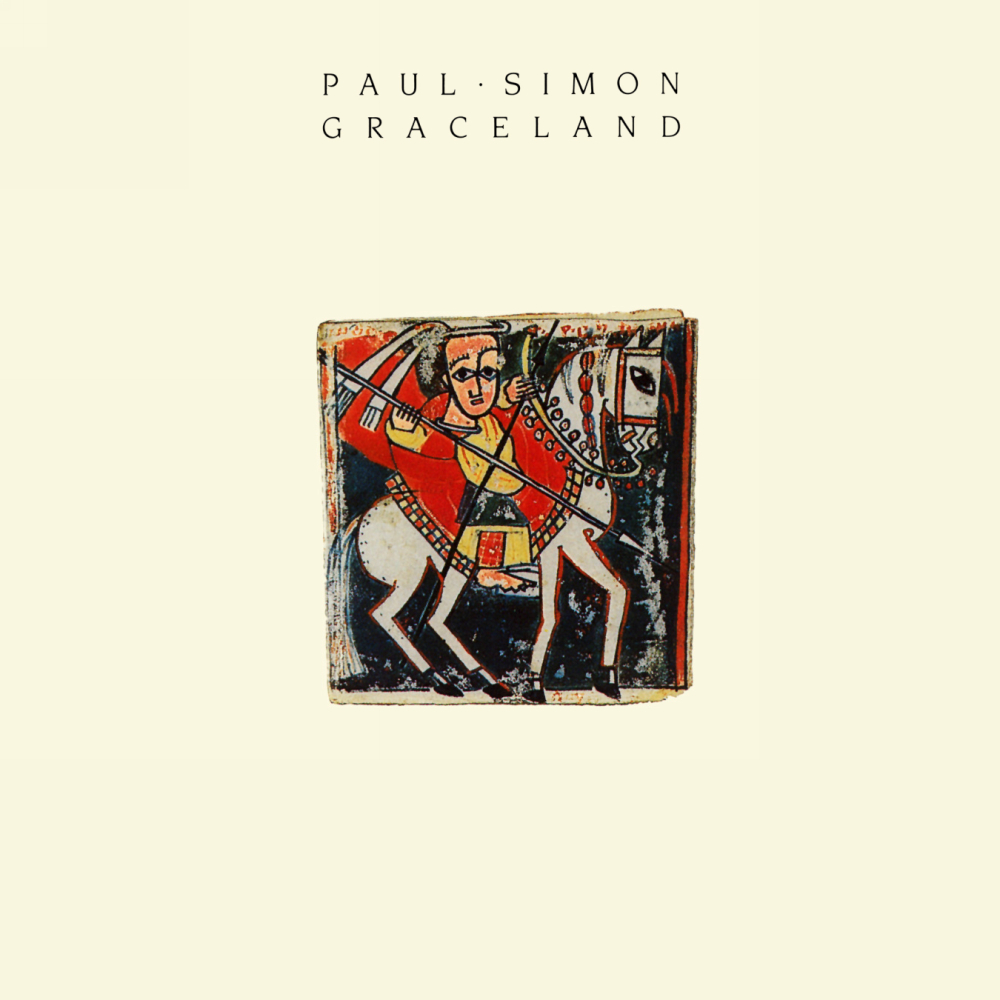

Paul Simon

Just to say that Ezra Koenig was something like

two-and-a-half years old when Graceland came out, and that one of the more boneheaded reviews of the record at the time

praised the South African musicians for playing their instruments “with

vitality and honesty.” How does one play a musical instrument dishonestly? On

the I Love Music message board, one

of the responses to my piece on the record states: “Graceland is one of my

favorite albums ever I won't listen to alternative opinions under any

circumstances so there,” and the author of the post in question appears to be

named “art.” Who am I to argue with the giant responsible for such masterpieces

as Fate For Breakfast?

Eurythmics

In which the formerly trying-hard-to-be-hip duo surrender to

the demands of FM programmers and do a boring,

straight-down-the-middle-of-the-block-line AoR record of which this is the most

stupidly played and replayed example. The album was entitled Revenge, and was very popular with

people who didn’t buy albums. What do you mean, you need me to explain what

albums were? What am I, Lowell freaking Thomas?

The Stranglers

Laurie Latham produced again, and it’s a typical mid-period

Stranglers iron-fist-in-mutton-glove, though Hugh Cornwell’s snarl is more

noticeable than it was in things like “European Female,” as if the whole band

is just about ready to blast out and shriek proto-Merzbow no-tonality for a

hundred straight fifty-CD box sets. The song? It’s about Thatcherism, and the

modern world, and Chernobyl, and “Always The

Sun” may refer to the newspaper.

The Pretenders

I’m not sure where Chrissie Hynde was finding herself in the

middle of 1986. She didn’t really have a band, for a start; on the Get Close album, she expressed extreme

dissatisfaction with a Steve Lillywhite-produced cover of Hendrix’s “Room Full

Of Mirrors” (although it sounds more than fine to me). Specifically, she

thought drummer Martin Chambers had lost it – although, as she later admitted,

he was still severely traumatised from the loss of two former bandmates – and

so let him go. Reassembling, with Bob Clearmountain and Jimmy Iovine now

producing, and a room full of session musicians (one of whom was, by a

delicious irony, Mel Gaynor), Get Close

essentially turned into a Hynde solo album, with two songs about her children

(“My Baby” and “Hymn To Her”), a lot of funk, and “Don’t Get Me Wrong,”

apparently inspired equally by a British Airways in-flight call-signal (the

song’s central four-note melodic motif) and an attempt to “do” the Beatles.

Still with Jim Kerr at this point, Hynde’s state of mind

during this period could fairly be described as undirected – when Simple Minds

came back from touring, the Pretenders had to go off on tour, so the two never

really saw each other – and some of that uncertainty may be projected into the

song’s structure and performance, in which Hynde implies that this might be

great or just very temporary, with several sardonic nods to Kerr’s big visions

(“Upon a sea where the mystic moon/Is playing havoc with the tide”). But her

tone and the song’s ending are none too hopeful.

Dead Or Alive

Pete Burns sounding relatively low-key and unfussed here,

maybe because Stock, Aitken and Waterman have worked out how they’re going to

sound.

Haywoode

Her first name is Sidney, she was in Flick Colby’s Zoo

troupe for the later days of TOTP,

and “Roses” is moderately likeable bubblegum from industry pros Leeson and

Vale. Typical can’t live with/without ‘em fare; she wants to go, but then he

brings her roses – “WHAT? DO? I? DO?” she asks us. It’s a more convincing

conundrum than any of Phil Collins’ sweatier ones.

True Colors

Proof that in 1986 Cyndi was still hipper than Madge. On one side there was the iceberg, “DON’T

DIE OF IGNORANCE,” clinical staff wearing gloves or refusing to touch patients,

Section 28. On the other, a song originally written with Billy Steinberg’s

mother in mind, which was first offered to, but turned down by, Anne Murray,

but a song which, through circumstance, Lauper made her own and which became

unofficially resonant throughout the gay/LBGT community. Politically, this

record’s most radical song, and also its most sweetly sung. “You’re beau-ti-ful

like a rainbow,” whispers Lauper, as though saying goodbye.

Boris

What is this reactionary shit – “Because you’re everything a

woman ought to be/Sweet and kind and pure of mind/And beautiful to see?” Did

rock ‘n’ roll, or liberation, actually happen? Bear this in mind; no matter how

hip, cool and wacky you imagine the

eighties to have been, it was filled with gunky crap like this. It might as

well still have been 1952, which I gather was part of Thatcher’s big idea.

Rod For One’s Back

Yes, on this day of days I’m going to come down hard on this

lament about a lost soul wanting to go home to Scotland. Why? Not just because

Rod’s actually from Finchley and is a Scotsman only in his mind. But because –

despite his even writing the lyric – I just don’t believe him. Listen to

Frankie Miller’s “Caledonia” and you can palpate

the singer’s tearful confusion; he means

what he is singing. Whereas throwing in tropes like “Jacobite,” “Emerald Isle”

and “swirling pipes” is a tourist’s Hairy Highlander notion of Scotland (which

snows when you turn it upside down). It doesn’t even begin to accentuate the

heartache felt by people who are now uncomfortable living in a country where

they are jeered at, patronised, threatened and compared with Hitler. Rather

than deliberately being kept out of the charts and off the radio for political

reasons, “Every Beat Of My Heart” rose to number two. Stay with us, Scotland,

because tourists have money.

Peter Cetera

“I am the MAN who will FIGHT for your HONOUR!” Look, it was Karate Kid TWO for feck’s sake.

George Michael

"Dedicated to a memory" it says on the reverse

sleeve of the single, and on the sleeve's front there is a black-and-white

photograph of a man with his back turned to the camera, some distance away, walking

into a huge park, unutterably alone. Although Michael was still, at that point,

officially one half of Wham!, the record drips with pungent tears of reluctant

farewells, although its subtext is more elusive.

A far more complex and satisfying record than "Careless

Whisper" - and yet also a far simpler one - "A Different Corner"

can fairly be said to be the first entirely solo UK number one single, in that

it was entirely composed, sung, played and produced by the same person. It could

with equal fairness be described to the most radical of 1986's number ones;

there is no chorus, and the song's reflective cycle wafts by in placid echoes

of repetition. Comparisons were made at the time with Eno's Another Green World - that refractory

Harold Budd treated piano, the same steady, unobtrusive flow of electronics,

the distended vocal drones in the background (though the latter may also owe

something to the intro and outro of McLaren's "Madam Butterfly") -

and through its snow-white sleeve and aura of finality, a kinship with

"Atmosphere" was seen. This latter was not far-fetched, since George

Michael had recently appeared on a BBC2 arts programme where he reviewed, among

other things, Mark Johnson's book An

Ideal For Living: A History of Joy Division, and spoke warmly of their

music.

"A Different Corner" is indeed a remarkable piece

of music in that here, after four years, we finally see the real George Michael

emerging, out of the shuttlecocked shorts and faux-machismo, with a

finely-judged and emotionally open vocal performance worthy of an older and

sadder Cassidy or Donny, and it's a George Michael we could learn to love. And

yet, although he sounds more open than on any of his previous records, the real

meaning of the song had to remain buried for a dozen more years.

The giveaway comes in the lines, "I would promise you

all of my life/But to lose you would cut like a knife/So I don't dare." In

other words, he loves his best friend ("'Cos I've never come close in all

of these years/You are the only one to stop my tears") but he loves him

that way also, and he is tortured because he cannot bring himself to tell him

(his "I'm so scared" is the reddest of excoriating wounds) - the same

subtext compelled to remain within the shadows of "Johnny Remember

Me" and "Have I The Right?" The music's careful placidity is a

striking counterpart to his agonised voice - and where does that "And if

all that there is, is this feeling of being used" come in, when really

it's the paralysing fear of rejection that prevents him from getting close to

his desired Other but also stops him from moving away; the torture of lifelong

compromise - "I should go back to being lonely and confused/If I could...I

would...I swear." Then his unheard pledge also echoes into the far horizon,

just as the man retreats into the greenery, walking away...in silence.

Shakin’ Stevens

A glossy, mid-eighties AoR ballad. By Shakin’ Stevens. Did

his record company even know what to do with him by this point?

Whitney

We’ve done this song before, and she means it, like George

Benson and Kevin Rowland meant it. She’s also angrier, and more doomed, than

either.

Lionel Richie

Dancing On The Ceiling

is sometimes so laidback a record that it verges on the comatose. Certainly the

title song is the equivalent of your uncle doing the Charleston to the Meat

Puppets; “Say You, Say Me” is nonsense which should have been renamed “Just Say

No,” and “Ballerina Girl” is fundamentally wrong.

“Love Will Conquer All” didn’t do much as a single here - #45 plays #9 on Billboard – but it’s the great lost

Richie song, a lovely, shimmering ballad of reassurance done with Greg

Philliganes and Cynthia Weil, sung in duet with the excellent Marva King, and

featuring a wonderful, proto-Erykah Badu chord sequence of unanticipated

elegance (G major seventh, C seventh, F suspended second, A seventh [suspended

fourth], A seventh and D major seventh). Forgotten by me for a third of a

lifetime, this was a very welcome reminder (“Give love a chance”).

Red Box

What the hell were Red Box (on) about? Pioneering pop/world

music crossover? A KwikSave Thompson Twins? Old seventies heads trying to be

modern? Pretentious, overqualified hippy garbage which Radio 1 played instead

of LL Cool J or Age Of Chance? “Lean On Me” annoyed me hugely when it went top

three, and so did “For America” when it went top ten a year later. An assault

on Reagan’s assault on Grenada and Nicaragua? Perhaps, but it makes me grind my

teeth, so anaemic, bitty and inconclusive is it as a pop record. Whoever’s

singing backing vocals on it (Anthony Stewart Head is there). “For America” is

why Big Black’s Atomizer had to

happen.

Furs

Ah, gentlemen, you took so long to get here and you lost all

of what made you moderately interesting (for fake Robert Wyatt records you

can’t get much better than “Love My Way”). Flippy-floppy AoR in which Butler

reminds you that he used to be someone.

Parade

So what if the film’s rubbish? So was Purple Rain. As with Graceland,

Prince built up the songs from rhythm tracks upwards. But no other pop record

in 1986 was as ceaselessly inventive as Parade,

and maybe only very few pop records since 1967. “Christopher Tracy’s Parade”

starts off as Sgt Pepper being

ambushed by the strings from Septober

Energy (via Westbrook’s Marching Song)

and from there just gets darker and stranger, at least in part because of the

arrangements provided by Lennie Tristano’s old pupil Clare Fischer. “A New

Position” is “Sex Machine” without a James Brown. “I Wonder U” is a detuned

transistor radio trapped the other side of Maxinquaye.

“Under The Cherry Moon” is Dennis Potter’s idea of the twenties, the record’s

“When I’m Sixty-Four.” “Girls & Boys” toys with French kisses before the

whining “Cross The Tracks” Moog loses both patience and tonality before

thudding into “Life Can Be So Nice” which atomises into a Cubist jigsaw puzzle

of Bolan, Sheila E’s drumming as far out, and far in, as Susie Ibarra on Ten Freedom Summers, before CUTTING OFF

and leaving us in the lounge of Hell that is “Venus de Milo.”

Side two features more “conventional” songs, one of which

(“Kiss”) is the best pop song about sex ever recorded (whispered, always

suggested), culminating in the increasingly bitonal desert of

“Anotherloverholenyahead,” which Lena reckons is like James Brown marooned in

Joy Division’s wasteland. Thereafter there is nowhere to go except the patient,

acoustic elegy of “Sometimes It Snows In April.” Don’t you realise, listeners,

that something beautiful – perhaps even pop – is dying?

Infected

Not that that

worried The The. If Soul Mining were

a microcosm of eighties Britain as glimpsed from a basement in Lewisham, then Infected took on, and fought, the gloss.

Told off in the NME for not being the

Go-Betweens – but they slagged off Parade

and thought Mantronix’s Music Madness

was the end of civilisation, so who gave a fuck what they thought? Certainly

not the thousands of readers who deserted them – Infected is a terrific and big-sounding album, not headachy big

like Let’s Dance but as gleaming and

threatening as the Big Bang and the newly-opened M25. “Sweet Bird Of Truth” DID

sound like the end of the world – Johnson’s scrambled “We’re above the Gulf of

Arabia” was truly scary; exactly the sort of thing Bowie should have been doing

instead of dreck like “Time Will Crawl” – and “Heartland” frankly sends “For

America” out the door/window/continent/planet. Whereas the title song welcomes annihilation; he goes for “love,”

knowing that it will kill him, the closing angels at the elevator ready to send

him down to hell. “Dear God, God, God, GOD, slow train to dawn,”

he hisses with Neneh Cherry, and you’re down there with them.

This is highly unsettling stuff for a Christmas-time number

one TV-advertised hits album.

Dylan or Dylan?

They kept the record shops open on the Bank Holiday Monday

so that people could go in and buy “Rage Hard.” But it was no use. Holly’s

boring, climax-killing announcement, with sampled crowd noises, in the

introduction suggested nothing new or different, and a lot less. He begins by

impersonating Scott Walker, and then Martin Fry, before remembering to be

himself. But the song doesn’t have a song, and the lyric is the usual tired

parade of go-for-it tropes (“Don’t give up and don’t give in” etc.). Morley

called the second album Liverpool

because he knew that was where the band would soon be heading back. It was very

bad progressive rock which gave 1986 hard-hitters Red Box and It Bites a run

for their money, if not mine.

Why “Dylan or Dylan”? Because ZTT seemed obsessed with Dylan

Thomas not going gently into that good night; two songs on 1985’s Insignificance soundtrack, one of which

was sung by Roy Orbison, referenced the poem directly. But enough of books, the

audience screamed, what about some ACTION?

But they were busy watching the wildlife, and engaging in

other activities beginning with the letter “w.”

Meat ‘n’ Parr

“Rock ‘N’ Roll Mercenaries” is the latest contender for the

worst song ever to appear on Then Play

Long. “Money is power – power is FAME!” bark, unlovingly, a one-hit wonder

striving to have another one, and a temporarily washed-up performer who would

shortly be reduced to participating in a special edition of a now unmentionable

television game show, involving the Royal Family. The Loaf forgot to introduce

Parr onstage one night, Parr took umbrage, and they haven’t spoken since.

Everything that was wrong with the eighties, and rock music, and not

necessarily in that order.

Spandau Ballet

When you think about it, the sentiments of “Fight For

Ourselves” aren’t that far away from those of “Panic” – Britain is sinking and

something’s going to change, maybe violently. But the music, though making an

initial fist of presenting a “harder” Spandau, falls back on glossy soul clichés

all too soon, and future wannabe Conservative MP Tony Hadley evidently hadn’t a

clue what he was singing (“Well, if life is here before my eyes/I find it hard

to see”). How were the rest of us expected to receive it any differently?

Robert Palmer

Not that far away from “Infected” – “Oblivion is all you

crave” – “Addicted To Love” nevertheless carries something of a curse; Palmer,

Bernard Edwards (who played bass and produced) and Tony Thompson all died

young, while Terence Donovan, who directed the video, committed suicide. Still

stuck in the Power Station – the guitar solo is Andy Taylor’s – Palmer dimly

tries to recall 1974 tropes while knowing that doom is perhaps not that far

away. Kim Gordon’s intentionally blank reading, done in a ten-cent record booth

and heard on Ciccone Youth’s The White(y)

Album, is perhaps one of the records of the decade.

Moral: An end is coming. How courageous are we to grasp

another beginning?

Moral 2: And the dice are loaded. No matter how or where

they land, they always read “five.”

.png)

![NOW That's What I Call Music! - Now That's What I Call Music 7 [UK] Lyrics and Tracklist | Genius](https://images.genius.com/ddf782994b3161b40a7497d7f17d2cf1.546x546x1.jpg)