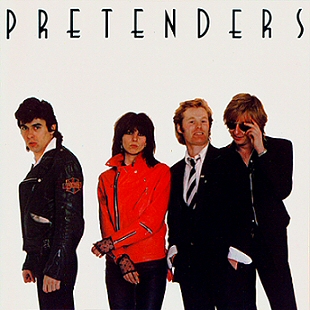

(#221: 19 January

1980, 4 weeks)

Track listing: Precious/The Phone Call/Up The Neck/Tattooed

Love Boys/Space Invader/The Wait/Stop Your Sobbing/Kid/Private Life/Brass in Pocket/Lovers

of Today/Mystery Achievement

“Change has a way of just walking up and punching me in the

face” – Veronica Mars

The scene now changes; this blog is now being written by two

people – Marcello Carlin and me, Lena Friesen.

For the rest of this blog’s (un)natural life we will both be writing

here, and it has been a long wait for me to arrive; in part because I am a bit

younger, and thus was a mere bystander to the on-going colourful slo-mo crash

which was the 1970s. So I am starting

right here, in 1980, with the first album I ever owned, knowing that this was

my new favourite band; that this was more than just an album, in some ways.

Let me set the scene; it’s Los Angeles, spring of 1980. At some point I get a radio with a tape deck

and earplugs; at some point, I get this album on cassette. I know nothing – repeat – nothing about punk. I am so naïve, I don’t even know about Joan

Jett, let alone the Runaways or the Ramones – I listen to Top 40 radio and

serious AOR stations and Dr. Demento and Rick Dees and KRLA with Art Laboe, who

will play oldies, particularly plaintive ballads for the low riders and those

who love them. New Wave is a concept I

understand; but the radio had so many great singles in ’79 that going out to

buy albums seemed unnecessary. Dr.

Demento plays the anti-disco anthem out of Chicago and I am suddenly aware

there are disco-haters out there, people who would hate my neighbourhood in

L.A. – Silverlake - where the Toy Tiger and the Frog Pond are local gay

clubs. The New Wave hits keep coming (I

now understand some of them as New Pop) – Gary Numan’s “Cars” and M’s “Pop

Musik” and even Tusk could be seen as

a New Pop gesture. As 1979 waned, there

was an impatience in the air, an eagerness, to see this decade out, gone, never

to return. A decade of men who could not

be trusted, disaster after disaster, the whole way through. But it was also a

time when women were, Equal Rights Amendment or not, gaining strength and

dominating the radio – Debbie Harry, Donna Summer, Stevie Nicks, Christine

McVie and Linda Ronstadt, to name a few that could be heard at almost any given

time on L.A. radio, sometimes on FM for a whole commercial-free half hour.

But then Pretenders

came out, and assumed (for me, anyway) an overwhelming prominence. I had just turned 13; I’d had a radio for two

years, had listened dutifully to it for that time, and had never heard anything

even close to this. I was still learning about the history of

rock ‘n’ roll at the time, and unwittingly bought only one of the most

important albums ever; absorbing it, assimilating it, and realizing slowly that

this was new, with the equally

newfound arrogance of the teenager who believes she has a favourite band that

was far superior to anything else,

and that everything in the future would have to be as good as this or she just wouldn’t bother with

it. I listened to Pink Floyd’s The Wall

because the serious heads at KMET told me it was an instant classic, and I was

impressed; but its deeper meanings, because I was naïve, were lost on me. (I had no idea who Syd Barrett was, and FM

radio never played any Syd-era Floyd.)

But no one needed to tell me Pretenders

was a classic; it was mine, and

needed no hype.

The album tells a story; so I will go through it song by

song. The band were named after the song

“The Great Pretender” by The Platters – Chrissie Hynde had a pal who, when he

was in a bad mood, would go into his room and play the song over and over. It is a song about being brave and showing no

misery after a breakup; one of many songs where the man pretends to be happy

when he isn’t. At first Hynde makes it

very clear that she isn’t pretending…but is she?

“Precious” is a song of – well, from the first drumstick

clicks and inchoate yells, this is not your ordinary song. Hell no.

Hynde and James Honeyman-Scott’s guitars surge back and forth so

intensely that you know there’s a tug-of-war here; between the nervous narrator

(because this album is so autobiographical I will just call the narrator Hynde)

and the superior proto-preppie she’s with, the big frog in the small pond

(small in Hynde’s view) who leaves her with a “bruised hip” but also makes her

feel like she’s “shitting bricks” as she knows she can’t live up to whatever he

wants from her. Swearing! Swearing, dammit! It has taken us this long to get to a woman

who really doesn’t give a crap and is going to swear, is going to make a lot of those guys who run radio stations

a little…nervous. The song’s not even

over and I love it already; the dive-bombing guitar as she goes into the break

wherein she seems to make fun of…the idea of having a baby which automatically cancels out a thousand ‘baby’

lyrics in so many tacky songs. The

conventional life of a suburban Akron teenager was supposed to aspire to,

accept. You can just tell she’s not going to settle for that, no way,

and then it gets very quiet; Hynde’s voice is miked very close, her every

breath and inflection can always be heard.

“Trapped in a world that they never made” is what anyone in the 1970s

could say, and when Hynde then says, heroically, “Well not me baby I’m too

crazy – fuck off” it’s as if the 1970s barely existed. They’re dead, as Hynde escapes in 1973 to be

in a rock band in London, come hell or high water. The push-and-pull ends, Honeyman-Scott gets

the visa and plane ticket and the door all but shuts at the end, Martin

Chambers’ drums providing the slam.

And that’s just how it starts.

“The Phone Call” is one of the many songs here (the album

didn’t, and still doesn’t, come with lyrics, and in 1980 you just had to make

them out yourself as best you could) that I never really understood, other than

it was in an odd time signature (7/8) and was about someone getting a call that

was urgent, from a callbox, with the phone ringing and ringing on the other

end. The song is urgent, claustrophobic,

fixated on the one thing; the security of whoever is supposed to get these

messages – a spy? A woman in danger? A gang member? If this is another song about escape, it is

an escape that is full of running, sudden stops, pieces of paper shoved under

doors – it’s a getaway car ready with the motor running. “This is a mercy mission” she says, her voice

muffled as PJ Harvey’s will be one day, with the guitars ascending and

descending like the breathing of a nervous person, willing themselves to be

calm, only just holding out. It ends

with a long exhale of final freedom, with the phone back again, the line

engaged. Beep-beep-beep-beep; you hope

the person who is there heard about the parcels in the mail. There is danger everywhere, this is the

1970s; or should I say, the 1970s themselves had to be fled, to be

escaped. (This album, quite pointedly,

doesn’t sound like anything from the

1970s or earlier.) So are we free yet?

“Up The Neck” is a laid-back song about “anger and lust”

that is just as claustrophobic in its way as “The Phone Call” except now it’s

the apartment, the flat, and not the callbox that’s the setting. The gruesome relationship is spelt out with a

veteran’s sneer from Hynde on the one hand, and a kind of crushed innocence on

the other. “Under the bed with my teeth

sunk into my own…flesh” is how badly she feels one morning – UNPRECEDENTED here

in Then Play Long, and her

description of sweaty sex as “it was all very…’run-of-the-mill’” then followed

by how the relationship was full of “bondage to lust” – the two people as

physical beings only, with nothing else between them. Her continuing cries of “I said, baby? Oh, sweetheart…” grow less ironic as she

realizes that that’s all there is. Sticky

shag rugs, dirty tiles, tongues and lips and bulging veins…and then the

relationship dies, the guitars churn and churn mechanically, the ease of the

song gone, evaporated. The relationship

never got above the neck; it was all kisses and slugs, no heart. She walks out, sorry and rueful, sadder but

wiser. (How many girls like me learned

so much from this, as opposed to the cheery advice columns in Seventeen or Glamour?)

Pretenders was an

album bought by girls, after all. And

guys too; Hynde’s no-bullshit singing/songwriting was a fresh breeze at the

time, and a big corrective to having to listen to “Whole Lotta Love” and other

such paeans to the female sex yet another

time. And the next song is one of those

that simply separates – as if the three before hadn’t already – this from

anything else even thinkable in rock ‘n’ roll at the time. For one thing it’s a 7/4 -4/4 time signature,

meaning producer Chris Thomas had his hands full trying to keep this erratic

and wild song from coming right off the damn rails. That he and the band could do it was a

testament to their intense rehearsing and gigging, meaning that the album was

done quickly and (I assume, I don’t know this for sure) as live as possible. This is a band,

after all, Chrissie’s band, and the unity and skills shown by everyone here is

amazing. Along with Hynde’s voice, the

band is also close, all the better to emphasize the intimacy of the songs; you

feel as if you are there, though Hynde’s voice is the guide, letting you in on

some things while leaving other things to your imagination, which Hynde assumes

you have.

“Tattooed Love Boys” rings like a bell and before you know

it, the struggle is on. “Little tease – but I didn’t mean it…but you

mess with the goods doll, you gotta pay, yeah…”

Her “tease” is squeaked out as if maybe she wants to, and maybe, she

doesn’t. She knows how to flirt, but

she’s not with the flirty types; these are bad boys, the kind she’s read

about…and now here they are.

The song comes to a stop after yet another unprecedented lyric: “I shot my mouth off and you showed me what

that hole is for” and here Honeyman-Scott stings, floats, wrenches his guitar,

bitter and fierce, as Hynde groans and says “oh baby baby baby” as if reinventing

the blues, the band then leaping from one speed to another out of the mystery

of what happened to the consequences.

Well, it’s not pretty for him; “you’re gonna make some plastic surgeon a

rich man” she crows, with the song ending with nothing but contempt for her

would-be…attacker? Rapist? “Another

human interest story…YOU ARE THAT.” And

the song ends, abruptly as it started.

Our heroic narrator survives hanging out with some tough guys who maybe,

really, aren’t so tough. She is not

singing those kind of blues – not yet, anyway.

“Space Invader” is an instrumental – one that points back to

1970s rock and yet lighter, simpler, pacing around at its root like a lioness

stalking prey, or for that matter someone playing the video game of the same

name that is sampled at the end. “The pulse

of the new” as I noted, and this is where Pete Farndon and Honeyman-Scott shine;

the song is like a knot being tied and untied, yet another breakaway from the

past, the bomb effectively dropping, the past being destroyed, for lack of a

better word. (Already I can sense all

sorts of guitar players, teenagers and rock stars alike, listening to this

album and playing along, from Johnny Marr to Lindsey Buckingham, from Courtney

Love to Neil Young.) The bravado and heroism

continue.

“The Wait” is yet another song that is sung so quickly and

rhythmically that just what it’s about and what is going on is only

half-understandable; even knowing the lyrics now I still don’t know what it’s

about, besides a child who is forgotten, alone, kicking a ball up and down the

street, an outcast, a loner, who is hurting and who only Hynde seems to care

about. But there is the wait; something

is coming, something Hynde knows is coming that in the tense breaks of the song

– again it is one that is brutally physical, meant for pogoing (in 14/8 time

what else can you do?) – and you can

hear her breathe as if she has run in the studio, as if she is actually waiting

along with the hapless “child” for The New to occur. Hynde is particularly vocal here, calling

out, snarling, as the song yanks itself this way and that. Honeyman-Scott’s guitar after the break is

nearly atonal, as if he is trying to make the ugly beautiful, the beautiful

ugly; in part I think this is due to his not really enjoying doing guitar solos

as such, so they tend to be brief and to the point, sardonic even, a good match

for Hynde’s voice.

“Stop Your Sobbing” was, as I eventually understood it,

their first single, produced by Nick Lowe; it is a song by The Kinks, one I had

never heard, and yet another turning-around of rock conventions – Hynde is now

singing to some guy that it’s about time he laughed and had fun instead of just

crying and bringing her down. Here the

band prove that yes, they can play your normal 1960s pop just as well as

anything else; and it continues the theme of the crying man, unable to hide his

emotions. (“Stop snivelling!” she yells

at the guy in “Tattooed Love Boys” – as if she’s

the guy now, and he’s the weaker sex.

Hmmmm….) Jangly fun, but Hynde’s

doubled voice at the end is desperate, as if she is somehow singing to herself

as much as him; even from the start, there is the undercurrent of never quite

knowing what is going on, in these songs, despite the authority and power of

them. It’s itchy and uneasy. Even the future she writes for herself here –

meeting and falling in love with Ray Davies, who wrote the song – is going to

be unpredictable and troublesome.

“Kid” is by far the most ‘normal’ song here, echoing Hynde’s

beloved Beatles; the boy is ashamed of something, feels it’s wrong, and won’t

hold her hand; why we never know. He

leaves, too proud to cry, though she begs him to cover his face, and Hynde’s

voice is direct and yet full of the blues and sorrow that he can’t accept her

for what she is; the situation is hopeless, and the song is cheery and upbeat

as the scene is quiet, final. “Kid, my

only kid” – he goes, beautiful and young and uncaring, it seems, about her

feelings. The album is suddenly

revealing (literally; this is the other side) that Hynde isn’t just a tough

chick from Ohio who has been the victim and victor in physical

encounters*. There is another side here,

one where a guy will just dump her, and she longs for him, “full of grace” but

it doesn’t matter. Write a pretty song

about it and have a hit single, I can imagine Hynde thinking; and so they

did. But then, Hynde finds herself in a

whole other situation.

“Private Life” is a slow reggae – menacing, erupting with

nagging/nail-digging solos from Honeyman-Scott that emphasize just how

impossible the title really is. A wife –

unhappy, theatrical – comes to Hynde and pleads for advice, help. Hynde pushes her away, dismisses her like

dirt: “Your marriage is a tragedy but

it’s not my concern.” But the woman

continues, complaining about her sex life, about everything, and Hynde just

tells her to leave the “somebody you deplore” and accuses the wife of

“emotional blackmail.” Pity, contempt,

hatred; she asks continually to be left out of the whole mess, but the pressure

builds and builds, and none of Hynde’s tactics here seem to work. Hynde moans with pain as the guitars pierce

her side; “Oh you’re mean!” she says, dying of a thousand insinuations and

threats. Does she give in? Has she met her match? It ends so quickly it’s hard to know, but the

pressure breaks, and now there is no escape.

Hynde the Heroic of the first side is no longer able to conquer; the

lies and stories and constant talking of the wife are too much.

After this, “Brass in Pocket” can be seen as a relief but

also as a sharp irony. Here is she is,

detailing everything about her that is so special, but it seems like an

inventory mostly to impress herself; she’s all ready to go, but is anyone

actually noticing her? Again the lyrics

and music go arm-in-arm, slinking down the street, but the attention she craves

never seems to come, and she is alone at the end, and maybe someone noticed her

and maybe someone didn’t. She’s got so

much to show, to tell, but there is an odd emptiness in the song, a kind of

false hope that if she likes herself so much, then surely there must be

somebody out there who will really appreciate her. She stood up for herself in the first song,

after all; but since then has yet to find that right person. And then…

And then she does meet someone; and there they are, late at

night, in bed. He is crying (again,

there’s no explanation; he just is) and it is breaking Hynde’s heart. The

delicate figures of the song – hesitating, hoping – as she tries to comfort

him, tells him that he makes the birds sing and the stars shine – the song

leaps up to the dramatic, as Hynde wails her “oooohhh” and their relationship

falters, as she tries – tries – to

talk to him. Hynde sounds as if she is

finally crying too; the whole song is a lament for those who are scared to see

people in love, people brave enough to take a chance, and for those who are too

scared of having their hearts broken to get involved in the first place. (If Brett Anderson owned this album, as I’m

sure he did, this is the song that undoubtedly influenced him the most.) The break is power chord glory mixed with an

acidic lace, that this is how it

ends. She has tried and tried and found

boys and kids and mere children to care about, and now (presumably when she is

truly in love, not lust, not bondage) she has to face herself and know herself

with as much acuteness as she has brought to bear on everyone else. And it’s terrifying.

“No…noooo…” she sings over and over, in total

disbelief. It’s the loneliest and

coldest feeling in the world, this one.

She can’t leave and shut the door on it.

Because for once it’s not him; it’s her. “No…I’ll never feel like a man in a man’s

world.” The whole album, nearly, leads

up to that moment, as the song fades, as the relationship is engulfed by the

sky, the birds, as being a woman is something she has tried to escape, to

pretend wasn’t real, that she could move to London and be one of the blokes in

a band and hang out with her punk band friends and never get hurt – the

vagabond above the law. But there’s law,

and there’s what you can’t escape from, which is yourself. She sings a lullaby but sounds as if she’s

about to have some kind of breakdown herself; that promise of whoo-hoo

self-definition badass which got her this far is of no more use. So now what?

“Mystery Achievement” looks at the facts straight; where is

her sandy beach? What is success, in or

outside of the band? She just wants to

have fun, be in a band, get drunk and dance the Cuban slide but the trophies

–the promise of fame and fortune – she could care less about. (How many debut albums come with a song about

how the singer doesn’t actually want to be famous?) The song is a classic of a

sort – drums first, followed by an audible Hynde sigh, then bass, then

guitars. Her worried “oohhs” are all

over the place, and the instrumental break is one of joy; you can hear all the

band somehow talking to each other, Hynde’s voice coming in for what sounds

like her real happiness – finally she

has her own band, they’re doing her

songs, and they are having fun doing them.

(That a bit of it sounds like Magazine is par for the course; I mean,

who wasn’t listening to them at this time?)

That she has done all this, had hit singles, survived the 1970s – seems

unreal to her, as if it was a bad dream, that she is being rewarded for all the

wrong reasons.

.

Privately she may be the woman looking for the one good man,

but here in her band, she has gotten what she has had to work hard to achieve;

what she set out in 1973 to do, while those in Ohio called her crazy. She was virtually the last one of the Sex

shop on King’s Road set to get a band together, to play gigs (the first on the

day Sid Vicious died), to make music so stunning that this album was the first

debut album by anyone to enter the UK charts at #1. This

was in part due to anticipation of the band’s fans, but word of mouth as well,

from girl to girl, woman to woman: she

is telling it like it is. Pete Townsend found it, well, compulsive

listening as did I; there was nothing else like it, and it jolted just about anyone

who heard it (including fellow rhythm guitarist John Lennon) into some kind of

action. Words like “tough” and “tender”

are used to describe Hynde and this album, but her voice has a piercing urgency

to it that make generalities like those pointless.

This album is a record (literally) of courage; of chances

that led to ugly disasters, bodily harm, but also self-knowledge, to where she

ends with a kind of Zen knowledge/not-knowledge situation. She has a lot to learn, but at least she

knows what it is she doesn’t know (hello Juliana Hatfield) and what she does; a

heart that hurts is a heart that works, and being a woman in a band/a woman

otherwise doesn’t have to be – cannot be – an either/or proposition. Hynde showed a whole generation or two how it

could be done; how to be frank and noble and most importantly, be herself and have her own band. One woman talks and sings the truth of her

life, and a whole world opens up; a world that leads to Sinead and Alanis, to

Madonna (who saw The Pretenders live in 1980 in Central Park**) and L7, but

just as importantly, to all the young future Britpop stars like Justine and

Brett and Damon, who all inherited different aspects of the band’s works. (Heck, even Katy Perry cites Hynde as an

inspiration, but then her first album is called One Of The Boys,

which this album could’ve been called, too.)

The Pretenders succeeded where The Clash, Hynde’s friends from way back,

couldn’t; as great as London Calling is, this is what the public wanted***, and the plethora of female

voices now springs from only a few voices from the past; and Hynde’s is one of

them.****

This was a band that was almost too intense and brilliant to

last; just months after the unnecessarily rushed Pretenders II,

Honeyman-Scott died of heart failure in June of 1982, just a day after Pete

Farndon was dismissed from the band – Farndon died less than a year later. Hynde and Chambers found a new guitarist and

bassist, Robbie McIntosh and Malcolm Foster, and continued to record startling

singles and a blazing album, Learning

To Crawl, the band on the cover dressed in black, as if still in

mourning. At the same time she was in

love with a new man, and I will be getting back to that relationship in a few years…

And so at 13 I realized that it was possible to go somewhere else - this mysterious place called London - and I looked up to Hynde as a model of what I could possibly, just possibly, be...an American girl in London. I realized there were other places to live, other countries (besides Canada, where I'd already been and would return to sooner than I'd thought)...and as I took Hynde as a role model, I realized there was more to the world, more in the world, and that it was right to be romantic and heartbroken, as long as I kept going. And so I am writing this in London, a place I never thought back then I would get to visit, let alone reside in. But I did visit, and years later, did move. This album started that whole process, that opening up of possibilities.

What else can 1980 offer?

As she sings in "Brass In Pocket" Hynde is “Detroit leaning.”

And so off to Michigan we go…

*Hynde was attacked by Nick Kent one day in the Sex shop; he

beat her with a cheap belt as she tried her best to hide. The album makes it sound as if she dealt out

karate chops to guys, but in reality Vivienne Westwood thought she was causing

a disruption, and thence Hynde was dismissed and oh-so-coincidentally later

Nick Kent was beaten up at a Sex Pistols gig.

**The live version of “Precious” on their EP is from this same concert. It is, if you can believe it, even faster and

more intense than the original.

***Note how these days bands like The Specials (whom Hynde

also knew) and The Clash will go on the radio and reminisce about ’79-’80 while

Hynde pointedly refuses to indulge in any sort of nostalgic looking back. This is more proof, I feel, that Pretenders is a far more rebellious and

troublesome album for all concerned, and a lot of the songs still aren’t ‘radio

friendly.’

****Hynde herself would acknowledge Sandie Shaw and Joni Mitchell

as influences, even as she would downplay her own singing and guitar

playing. Part of her appeal is that

she’s not a diva in any sense, and is very much someone who would say “If I can

do it you can do it, if you have the nerve.”