Nick Heyward was

artful about his lyrics not "meaning" anything. Of course they did. They

existed to justify his life and to add punctum to the music (as was

proved by what Haircut One Hundred minus Heyward ended up sounding like a

year or two later; essentially, a low-budget Shakatak). The

"surrealism" worked because it was not intended to be surreal; like

Billy MacKenzie, it just seemed to come out of him. It felt necessary

at the time, rather than the grafted-on, sweated-at incomprehensibility

of lyrics with which this 1983 story will make us wearily familiar.

Listening to it over thirty years later, what strikes me most about Pelican West

is the astute fusion which Haircut One Hundred achieved between three

very separate strands of then-contemporary pop developments; firstly,

the franticity inherited from the No Wave/James Chance/Zé Records mob -

hear the near epilepsy of the rapid funk guitar strokes in "Favourite

Shirts (Boy Meets Girl)" complete with horn section deliberately laying

back half a beat, knowing when to come in or to stay out (they are

rushing to get the song played, to make it exist before everything else

ceases to exist).

Secondly, the

apparent effortless proficiency and attention to middle-range sonic

detail which came from the still unheralded Britfunkers of the time -

Beggar and Co, Light of the World, Central Line, Freeez - and in

particular the way in which ambiences from American funk/rock were

appropriated and adapted easily into a British environment.

Thirdly - and this

is the most obvious legacy from the Orange Juice/Postcard side of things

- an alert awareness of chimerical "pure pop" elements (Beatles

harmonies, McGuinn guitars, even a foreshadowing of the lo-fi of Beat

Happening/K) without being trapped within the Camden Town Good Music

Society cul-de-sac.

Even the two

elements of the title "Favourite Shirts (Boy Meets Girl)" attend to this

duality, as did the visuals - Heyward in his daintily knitted Fair Isle

cardigans, one shirt collar dutifully poking out from underneath,

guitar held high and at right angles to his body. No suits, no "sweat"

even. Girls loved it and knew immediately what he was trying to

communicate, particularly in front of what would otherwise have come

across as a weekend jazz-funk scratch band. Except of course they were

no scratch band - despite the artful naivety of the music, the songs

demanded chops.

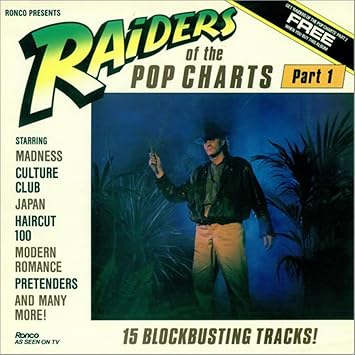

"Love Plus One," which appears on Raiders,

is driven by a marimba, which always results in great romantic pop

("Just My Imagination," "And I Love You So"), and its amiable canter is

counterpointed by the double-time attack of the drums and guitars. Hear

in particular how Heyward's guitar excitedly speeds up into "Favourite

Shirts" mode in the final chorus as he exclaims "Ring ANNA ring ANNA!"

and also the foursquare yawning bass introduction into the song’s main

body (Heyward at times here sounds as bucolic as Andy Partridge, and

XTC’s contemporaneous English Settlement is a nice

parallel case study for someone with more time and resources than me to

tackle). Sublime pop on at least four different levels, and deservedly

their biggest single (#3 in January 1982).

Chops? "Lemon Fire

Brigade" saw to that. And the blissful spring in this track's step is

what Danny Baker picked up on in his brilliant review of Pelican West in the NME.

Here, at long last in British music, was a group throwing the gauntlet

down to the Americans and able to compete. The lovely, largely

instrumental, track is, as Baker noted, worthy of Steely Dan, and is

made all the better by Heyward's sole, plaintive lyric, "Why, oh

why?/Lemon Fire Brigade/WHY?" It was this element on which less astute

descendents subsequently picked up and polished to the point of

lifelessness, without any of the mischief or interest (we will come

across them in 1987 or thereabouts).

The slowly-demisting

"Marine Boy" initially reminds me, at least instrumentally, of Joy

Division; that vague fog of uncertainty, before the skies clear, as they

must. "Milk Film" is exuberant power-pop (there's no other word for it)

but with a distinctly English sensibility. There's little more

exhilarating in 1982 pop than Heyward singing at this song's climax

"Glad that I live am I/Glad that the sky is blue/Glad for the country

lanes" - and this is no John Major-misquoting-Orwell utopia either, but a

more palpable one. The song tells you, in its own sweet-natured way,

not to die (listen out for the brief Elvis Costello send-up when Heyward

sings "mountain").

Thereafter the album

switches between pre-post modern jazz-funk and blissful

1968-as-it-never-actually-was pop. Of the former, "Kingsize," "Baked

Bean" and "Love's Got Me In Triangles" are essentially a poppier Pigbag,

elevated by Heyward's escalatingly bizarre non-sequiturs and

untranslatable yelps. If anyone today quoted Toblerone in their lyrics

(as Heyward does in "Triangles") it would be beyond the Robbie

Williams-imposed pale. Here, it strikes you as entirely logical.

"Fantastic Day" is

"Milk Film" as spring liquefies into summer (the "Penny Lane" trumpets).

I love how Heyward always gets more excited - and the way in which the

band surreptitiously speed up - the nearer he gets to the end of the

song. Listen to his "'cause I'm SO in LOVE with YOU!" in the final verse

of "Fantastic Day," puncturing the opiate shimmer of the saxophones in

the mid-ground (excellent sax playing by Phil Smith throughout, by the

way, even indulging in a few harmolodics on "Baked Bean").

"Snow Girl" would be

a number one for anyone now; but would they have the arranging genius

to include the orgasmic, out-of-tempo blissout which arrives

unexpectedly in the middle of the song, Vincent Sullivan's trombone

sliding into infinity behind Heyward's craving for the Other's "elbow"? I

doubt it. And the Butterflies of Love would have to labour for several

further decades of archiving before coming up with such a "perfect pop"

song as "Surprise Me Again." The song is constructed as a double-bluff;

initially Heyward seems to be breaking up with the Other ("At the start

it was great/In the middle I stayed/But at the end I was sick" is a

precis as good and acute as Costello at his hungry best), but listen to

how the whole band suddenly swings up into the sunlight with him as he

sings "then suddenly you smiled." Such an ecstatic chorus. Such hope.

Such a future.

Nothing left to do

now but to wrap everything up, which they do with "Calling Captain

Autumn." Another funkout, but crucially parenthesised by mock cricket

commentary, staged as though they were listening to it on the radio. So

this stands as a complete redefinition of "Englishness," incorporating

black elements, unimaginable without them (the Brixton riots were still

fresh in everyone's memory at the time, bear in mind), and a subversion

and ultimate rebuttal of what the Mail/Telegraph would want us to accept as England.

The fact that, by the beginning of 1983, all of this had effectively ceased to exist does not pass the astute listener by.

Clannad

There is something

quite startling about this fog of silence which drifts across the debris

of side one’s jollity, as well as a sign that, despite 1982 being

almost over, not all of the lessons of New Pop had been neglected. If

Japan’s “Ghosts” introduced the elements of deliberate silence and

stillness in a manner which pop had not hitherto known, then the

hourglass-like stillness – or the patient stillness of a sniper or

assassin – was returned to the table by Clannad.

Composed by the

group’s Pól Brennan as a theme to the Yorkshire Television thriller

series about the Northern Irish Troubles, lead singer Moya Brennan

trembles her way authoritatively through her lament – and lament it be,

the lyric (sung entirely in Irish Gaelic, an attribute which no other

hit single yet boasts) comes down to saying that in times of war and

violence, no side will win, and all sides will lose (the song is very

careful not to take sides). There are long periods of the record which

consist of nothing more than Eno (or Avalon?)-type

ambient Fairlight drones. As pop was largely, and already, straining

towards insisting that things be done NOW and FAST, this was radical,

and a dire warning to the pop to come in its (literal) wake.

(As this song is

routinely attributed to the younger Enya, it should be noted that Enya,

in 1982 still only twenty-one, had already been and gone as a member of

Clannad; the long-term effects of “Theme From Harry’s Game” would be felt dramatically less than six years hence.)

Raw Silk

My 12” of “Do It For

The Music” begins with the echoing vocal: “No time for criticisin’,”

but evidently (i.e. by this evidence) the 7” didn’t (instead we get a

cough). Never mind; like fellow Nick Martinelli-mixed “Beat The Street”

by Sharon Redd, this was inescapable in late 1982 London, and a fine

late disco hit it was too – they were a Crown Heights Affair spinoff

(and the group’s Bert Reid may be responsible for the probing tenor sax

solo) and the song’s easy, patient drive probably renders it undanceable

in today’s climate - but the extraordinary high notes (“Do it for me,”

“DO IIIIIIIT!” – Jessica Cleaves, I think, was the lead singer here) are

relishable, before she glides back down to a more comfortable mid-range

which, frankly, reminds me of Sarah Cracknell.

The Chaps

No, I wasn’t able to

find out who they were either, except that this came out as a single on

Stiff – catalogue number: PRAW 1 – and is the old Frankie Laine cowboy

theme sung in a possibly fake Glaswegian accent with asides of the

calibre of “Haggis, beer an’ fishin’” and “Pints of heavy in East

Kilbride,” continued fourth-wall critiques of the record and an

accordion which bursts randomly into “The Black Bear” or “I Belong To

Glasgow.” Like the previous year’s “Hokey Cokey,” a Christmas Top 20 hit

for “The Snowmen,” (a) this may or may not have been the work of

Extremely Famous People messing about, and (b) I could care less. It’s a

bit like a younger KLF covering McLaren’s “Duck For The Oyster.”

Perhaps I am making it sound too interesting. I don’t remember it being

played at all on radio at the time.

Incantation

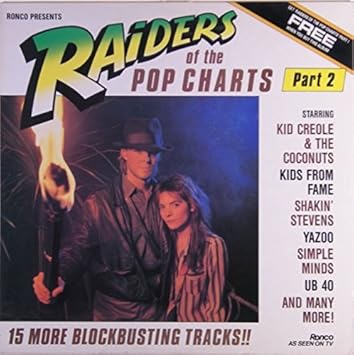

Side one of Raiders

is useful in a globetrotting way; three years before the marketing

concept of “World Music” was invented, we’ve been to Ireland, “Glasgow”

and now the Andes. Actually Incantation were a multinational group of

musicians writing for the Ballet Rambert, who collaborated on a

successful 1981 production entitled Ghost Dances; the success won them a recording contract, and their second album Cacharpaya: Music Of The Andes,

with the help of a television series, made the top ten. The title track

went Top 20 as a single and is a harmless panpipe knees-up, making with

the accelerando at the end (the subtitle “Andes Bumpsa

Daesi” may give some notion that the music wasn’t to be taken too

seriously, even though nothing could really be taken more seriously than

the rebel music of Chile). They continued to prosper – they provided

the panpipes for many film productions, including The Mission. Most interestingly, however, Incantation member Simon Rogers eventually resurfaced as a member of The Fall, notably on 1985’s This Nation’s Saving Grace.

Fat Larry’s Band

One of several singles on this collection to peak at number two – and therefore to be discussed more fully in Music Sounds Better With Two

– “Zoom” in this context plays like the last ray of old-school soul

light before the future engulfs it. The band were from Philadelphia, and

despite occasional club favourites like “Center City” and “Act Like You

Know,” “Zoom” – co-written by Len Barry, of “1-2-3” fame – was their

moment; lead singer “Fat” Larry James’ performance, a semitone out of

tune, is perfectly charming, though the reversal of the standard

day-into-night light analogy is modestly startling. The song sounds like

a fond farewell, and James himself exited this world, from a heart

attack, in 1987, aged just thirty-eight.

Culture Club

The reviewer in Smash Hits

– a chap named David Hepworth - approvingly compared the single, and

its singer, to Dennis Brown, but there are many more aspects of

lightened loss to the voice of the artist previously known as

"Lieutenant Lush." He far more immediately calls to mind Ali Campbell,

of UB40, but his extraordinary purity is comparable with Russell

Tompkins Jnr, and there is even a touch of the polite vulnerability of

Neil Sedaka ("I have danced inside your eyes").

But there is

undoubtedly hurt here, bleeding through every nodule of the singer's

tonsils. What does he mean by "do you really want to hurt me?" With

pained references to "precious kisses, words that burn me," "let me love

and steal" and "if it's love you want from me then take it...away" (he

is on the verge of collapsing altogether on that "take it") it could be

about the fear of commitment, or spiritual as opposed to merely carnal

bonding. Or, as some commentators would have it, it's an extended mild

bitch at alleged ex Kirk Brandon.

But given the enormous controversy aroused by his performance of the song on TOTP - the first time Boy George had been exposed to the public at large beyond NME

addicts, Bow Wow Wow adherents and the London hipster circuit - and

also the video, shot in a courtroom, the question could viably be

interpreted as a rhetorical one; note that opening line of "Give me time

to realise my crime," as though he had committed any. Let me be, what

have I done to you, what makes a man a man - "Everything is not what you

see" (and several radio DJs who indeed "did not know" assumed that it

was a woman singing).

So "Do You Really

Want To Hurt Me?" is very close to a statement, or even a polemic, sent

out as New Pop declined into ignominious ambulance-chasing; but such a

serene setting. The first two Culture Club singles, "White Boy" and "I'm

Afraid Of Me," were promising but didn't yet live up to what writers

like Paul Morley was claiming about them - but everyone had to stop and

take notice of the third, for it was extremely special, and that rarest

of things, a natural number one.

The music is so

quiet and so deftly handled by the musicians; the mood is lovers' rock,

not so much in the manner of Dennis Brown than after the fact of such

great one-offs as Louisa Marks' "Caught You In A Lie" or Trevor Walters'

"Love Me Tonight." But the song continually bends down like an agonised

question mark, so elegant the transition from major to minor, so

reluctant the return. Roy Hay's sitar-guitar immediately recalls "You

Make Me Feel Brand New," but this is the sound of something, or

somebody, slowly dying; in the instrumental break just before the final

chorus, the swathes of dub synth winds blow like a shroud ready to be

laid, and right at the end, after the final sitar-guitar query, a drum

machine is revealed, and ticks on regardless.

Boy George's is one

of the great chart-topping vocal performances, and certainly the most

passionate and controlled of any 1982 number one – the only one of

thirty singles featured here to go all the way, in more ways than one -

you instinctively hurt in tandem with his desperate "hurt me"s in the

chorus, you trail away symmetrically with his wounded "cry." It turned

out to be Culture Club's first masterpiece, a fully deserved number one -

though it would take others, notably the polarised opposites of Jimmy

Somerville and Holly Johnson, to remove that shroud for good.

Pretenders

The single could

have been said to have ended a whole process, the closing down of

possibilities, not all of them voluntary. The song was originally meant

to be about Hynde and Ray Davies – thus the lyrical references to the

media, nostalgic glimpses back into a common, unreachable past (“Those

were the happiest days of my life,” Hynde’s voice vaults, not sure

whether to laugh out loud or cry in quiet), the pain in the apparent

knowledge that “the world,” not they, had sundered them apart.

That wasn’t quite

the whole truth – Hynde and Davies’ relationship was on the hurricane

side of stormy (love your idols? Do you dare?) – but by the time the

single was released it had all become academic, since guitarist James

Honeyman-Scott was by then dead from a drug overdose, dying one day

after bassist Pete Farndon was sacked (and Farndon didn’t have long to

live either) – and so the song became a reluctant requiem, a furtive

upside to the inward torment of the group’s version of Davies’ “I Go To

Sleep” (a top ten single in that darkest of months, November 1981) with

key changes and strange chords (including an E7 augmented by an F,

hitherto only heard in the Beatles’ “I Want To Tell You”) lending the

performance an unbearable poignancy (“And I’ll die as I stand here

today”).

Hynde and drummer

Martin Chambers were the only two “Pretenders” on the record – the other

musicians were guitarist Billy Bremner, on loan from Rockpile, and

bassist Tony Butler, shortly to become part of Big Country (I am not

sure who plays the “Love Will Tear Us Apart” synthesiser line at the

end, unless it is processed guitar) – and the single’s B-side, “My City

Was Gone,” which gave a picture of an Akron more unrecognisable and

derelict than anything Devo did, cemented the notion of pop single as

angry memorial. Both songs eventually resurfaced on 1984’s Learning To Crawl,

by which time The Pretenders had evolved into a rather different group;

but here it stands as a farewell to New Pop, sixties idealism, perhaps

even seventies punk – what happens when you go home and home cannot be

seen?

Japan

For the year or so

when Japan were popular – which, coincidentally or not, was the last

year or so of their existence – theirs was among the most confusing of

chart careers. Realising that they had been somewhat ahead of the curve,

their old label Ariola/Hansa reissued “Quiet Life” from 1979 and saw it

sail into the Top 20 in 1981. Simultaneously the group, now signed to

Virgin, were trying to promote their newer and more advanced work,

specifically the Tin Drum album. A stream of alternating

singles ensued from both sides which meant that two Japans were

effectively battling each other in the charts. Was the group which

slowed pop’s heartbeat to a chilling standstill with “Ghosts” the same

people responsible for a rather arch reading of “I Second That Emotion”?

I don’t know whether

too many people noticed, or were fully occupied covering their bedroom

walls with David Sylvian posters. Nonetheless, the threatening, quiet

brilliance of Tin Drum has not diminished in the

thirty-two years or so since it was first released – close down the

world with “Sons Of Pioneers” or the John Cale-ish celeste which

surfaces towards the end of “Cantonese Boy”; listen to “Still Lives In

Mobile Homes” and wonder just how enormous and silent an influence Joe

Zawinul was on New Pop – and “Ghosts,” as a single, performed motionless

by the group on TOTP in March 1982, Sylvian an

alabaster Osmond frozen by Medusa, or perhaps his own reflection, is one

of the most staggering achievements in all of pop; the ability to

navigate silence or near-silence, the lengthy stretches within the

lament where nothing seems to be happening save for the turmoil in the

singer’s mind, the sour ring-modulated trombones from Escalator,

a chord sequence worthy of Kenny Wheeler (with whom Sylvian would work

two years hence), a lament which stretches from Brian Hyland via David

Cassidy to Tricky (via Mark Stewart) – the world was there for the

taking, but something (the past? The singer’s own fears?) froze him in

his stealthy, scared path – all of this formed the bluntest, if

gentlest, challenge to the notion of the “pop song” (little wonder that,

several years hence, Sylvian would record a stand-alone single entitled

“Pop Song”). That pop songs didn’t need to be noisy. That being “in

your face” could represent an embrace rather than a challenge.

That there was a different road to take from the one which you expected to take.

By the time

“Nightporter” was released as a single in the late autumn of 1982, Japan

no longer existed. Students sitting in the Junior Common Room on

Thursday evening. Students watching the television. Students watching Top Of The Pops. The Top 40 countdown. It was Thursday 2 December 1982. 7:41 in the evening. Numbers 40-11.

At 29 it was a

six-place climber; “Nightporter” by Japan. Cheers swiftly followed by

boos when the countdown didn’t stop. They’re not going to be on? But

they’re climbing! Nobody knew then that Japan had ceased to exist. Were

not available to do Top Of The Pops.

At 28 it was a six-place faller; “Ooh La La La (Let’s Go Dancin’)” by Kool and the Gang. No reaction.

At 27 it was a

two-place climber; “It’s Raining Again” by Supertramp. A couple of

cheers from the back of the room. But the countdown did not stop.

At 26 it was a

seven-place faller; “Muscles” by Diana Ross. Written by Michael Jackson.

About his pet snake. It was agreed that he was a strange one, that

Michael Jackson.

At 25 it was a new entry; “Friends” by Shalamar. No reaction.

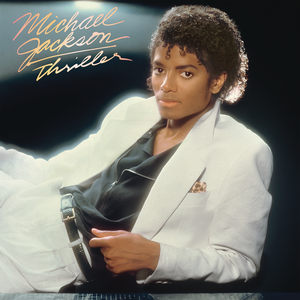

At 24 it was a

twelve-place faller; “That Girl Is Mine” by Michael Jackson and Paul

McCartney. It was agreed that he was a strange one, that Michael

Jackson. It was noted that the record hadn’t really done that well. And

that the new Michael Jackson album was no Off The Wall. Far from it. Students would go to Woolworth’s and point at the piles of unsold copies, laughing. It was really too bad.

At 23 it was a

three-place climber; “Talk Talk” by Talk Talk. Their debut single,

remixed but not so you would notice. A little more piano, perhaps. It

would have done. But the countdown didn’t stop.

At 22 it was a nine-place faller; “Cry Boy Cry” by Blue Zoo. Ye whit? said one voice. Who hell they? enquired another.

At 21 it was an eleven-place faller; “Maneater” by Daryl Hall and John Oates. No reaction.

At 20 it was a twelve-place faller; “Theme From Harry’s Game” by Clannad. Respectful murmurs. Deserved to do a lot better than number five.

At 19 it was a

four-place faller; “State Of Independence” by Donna Summer. Respectful

murmurs. Deserved to do a lot better than number fourteen.

And at 18 it was a

three-place climber; “Best Years Of Our Lives” by Modern Romance. The

camera dissolved to Modern Romance in the Top Of The Pops

studio. The group were waving their meaty hands and yippee-ing amidst

primary-coloured tinsel and small audiences pretending to be happy. The

students in the Junior Common Room let out an almighty, amplified SIGH

of exasperation and disappointment, with some supplementary “fucking

hell”s.

It was confirmed, at that moment, that “we” had lost.

But Japan were already lost.

“Nightporter” was

not even current Virgin Records and Tapes Japan. “Nightporter” was

already two years old, from a 1980 album entitled Gentlemen Take Polaroids.

Recorded at Air Studios, high above Oxford Circus. A transitional

record in several ways. Guitarist Rob Dean realised his redundancy and

left the group after the record was released. Ryuichi Sakamoto came on

board for the magisterial, record-closing “Taking Islands In Africa.”

Sylvian began to look beyond Japan, and had begun to wonder what other

musicians could bring to his own visions.

Air Studios

constituted a kernel of sociability. Paul and Linda McCartney were there

most nights, working. Linda was a huge Japan fan. Paul also liked them

and offered to do some guitar work on their songs if they needed it.

And there were these

kids from Birmingham, these five kids, working in the next studio to

Japan, and it was confirmed, at that moment, that “Japan,” and perhaps

pop music, had lost.

These five kids from

Birmingham were Japan fanatics. They nervously presented the group with

a rough demo tape. One song. “Girls On Film.” Japan spluttered amongst

themselves. What a pile of garbage! they thought. Like us a couple of

years ago, before we dropped all that nonsense, or Moroder eased it out

of us. But they are just kids from Birmingham. Be diplomatic. Tell them

we’re very sorry but we can’t produce them right now.

The five kids from

Birmingham took the rebuff well. Although the five kids from Birmingham

thought that they were already above such things as rebuffs. One of them

had gone up to the keyboard player for Japan, Richard Barbieri, and

told him: “We’re going to be bigger than you because we want it more.”

Barbieri smiled agreement. He knew they didn’t know what “it” they

wanted. But inwardly he sighed, knowing that yes, the five kids from

Birmingham were going to be “bigger” than amiably arty Lewisham/Catford

types Japan. If all they wanted was to be “bigger.” Bigger than life?

Japan remembered James Mason, Nicholas Ray and cortisone. Not one of

them thought that “God is wrong!”

Japan also remembered the 1974 European arthouse movie The Night Porter.

Dirk Bogarde and Charlotte Rampling. Bogarde played an ex-SS officer.

They treated business as pleasure and pain as payment. And so, this

slowly patient waltz, out of Satie, perhaps, but to the same extent that

Hampstead is out of Kelvingrove. Voice, piano, discreet electronics,

some woodwind and strings. This last, un-wild waltz. “Could I ever

explain this feeling of love?” Sylvian sang as though having examined

Cassidy, Osmond and Soul and found them all still wanting. The song

never lifts itself out of whispers. “Longing to touch all the places we

know we can hide/The width of a room that can hold so much pleasure

inside.” As Sunday stately and as acutely damaged internally as Ute

Lemper and Scott Walker’s “Scope J,” the lovers love, or paint a picture

of love. Dissipating in “a quiet town, where life gives in,” the man

waits for the night – like Fat Larry’s Band and Heaven 17 – so that he

can experience life again: “And catching my breath, we’ll both brave the

weather again.”

I lazily thought

that the additional instrumental colours were the work of Mick Karn. But

the oboe on “Nightporter” is not his, and the rustling, ascending

low-level leaf behind Sylvian’s voice is not that of a bass clarinet,

but of a bowed double bass.

The double bass

player was Barry Guy, the great improvising bassist and composer, one

third of Iskra 1903 and leader of the London Jazz Composers Orchestra.

And even though Guy,

in retrospect, recalled Japan's hairstyles more readily than he

remembered the session, I like to think that this is where the New Pop

nettle, before “New Pop” was even thought of as a phrase, was grasped,

that Sylvian knew that to survive it had to justify its glories and be

able to move music and life forward. And so he put the standards – the

Reed, the Bowie, the Dolls, the slide rule of historicism that

subsequent generations of musicians could or would not ease themselves

past – to the back and considered other ways, listening to musicians

creating on the spur of the moment, taking into account the record

labels which don’t routinely appear in pop music histories. Labels like

Incus, Ogun, Bead, Matchless, Mosaic, FMP, ECM, JAPO, ICP, BVHAAST,

Horo, Steam, Steeplechase, Tangent, Black Saint, Soul Note, Delmark,

Nessa, IAI.

Or perhaps Sylvian just listened attentively to BBC Radio 3’s Jazz In Britain broadcasts, particularly the one recorded in March 1980 by Barry Guy and the London Jazz Composers Orchestra – Stringer (Four Pieces For Orchestra)

– and in particular the second part, which was a slowly rising

palindromic compositional arch there to cushion the trumpet improvising

of featured Torontonian soloist Kenny Wheeler – a musician who, as mentioned above, by 1984,

would be working and recording with David Sylvian – and it is a

beautiful, oddly tonal, restrained reflection of somebody’s soul which

not so oddly is a little reminiscent, in mood if not in structure, of

Japan’s “Nightporter.” And eventually Sylvian would learn about more of

these players, and the players with or around or alongside them, and

grow. Gone To Earth, Blemish, Manafon – “Nightporter” marks the point where he, and New Pop, had already begun to grow.

Heaven 17

One could understand Heaven 17 being slightly frustrated by the autumn of 1982. Penthouse And Pavement was a permanent fixture in the album chart but they still hadn’t had a Top 40 single, the Music Of Quality And Distinction Volume One project had fizzled away somewhat, and the Human League were…well, what were the Human League doing in the autumn of 1982? The absence of “Mirror Man” from Raiders

can be ascribed to the fact that it was still riding high in the charts

of Christmas 1982, was in no immediate need of a commercial leg-up (but

its B-side, the ominous “You Remind Me Of Gold,” is the great lost

Human League song).

But by Christmas

1982 the Human League were no longer really what they had been in

January 1982, hadn’t fully come through on their promise. Then again, by

Christmas 1982 New Pop was no longer really what it had been in January

1982, hadn’t been allowed to come through fully on anybody’s promise.

The exclamation mark

at the end of “Let Me Go!” is necessary, to counteract the general air

of frustrated exhaustion that marks the record. The single cover

featured a close-up of Glenn Gregory, grasping a telephone receiver as

though ready to strangle it, looking at us, angry, confused and tired.

The sleeve’s grey shades make a striking contrast to Heaven 17’s

previous white-on-white/primary-coloured all-is-welcome façade.

The song was Heaven 17’s masterpiece. It is best experienced

in its 12-inch incarnation, as the mix carefully breaks down and

highlights all the features which make it such a great and apocalyptic

pop record:

- The

lonely Eno via Percy Faith single-note high synthesiser line providing

the counter-melody to Gregory’s lead – or was it obtained from the Bonzo

Dog Band’s “Slush,” Neil Innes’ laugh looped to hell and never back?

- John Wilson’s characteristically generous guitar chords, waddling, lost penguin synth bass and acoustic guitar commentary.

- The Free Design-out-of Sudden Sway vocal counterpoints (“Ba-do-do-ba-bo-ba-bo-bar-up-BOP!”).

- The eerily still harmonies which remind us that once there was 10cc and “I’m Not In Love.”

This

is the seven-inch edit, however, which gathers up all of these elements

at once. And the song – “Let Me Go!,” let New Pop go? – plays as though

it might be the last pop song ever recorded.

The

debris, the wreckage, lie around the group, and they are tidying up as

best they can after the threads have been cut forever, knowing that

their task is a necessarily forlorn one. From a funk-pop perspective the

song is Raw Silk taken to the next level.

And

yet Gregory’s voice, angry, confused and lost though it may be, is

always carefully controlled. Dignity – ALWAYS dignity. He sings at about

half the speed of the song, as though trying to catch the driftwood of

human life that has irretrievably fled into space, wondering where, how

and why everything went wrong, but knowing that this is the end, or an

end.

“Once we were years ahead, but now those thoughts are dead.”

There

once was life, an unbroken path, unspecified days of brilliance. But

now there is “a torture less sublime.” He knows that he tried (“a

thousand times”) but also that it just wasn’t enough, and that

everything from hope onward came crashing down. As though their scheme

had failed. Their strategy backfired.

Enough.

Enough’s enough.

Enough is enough.

“All I want is NIGHT TIME!”

“I don’t need the DAYTIME!”

Let there not be light if the only light to be glimpsed is a falsehood.

And yet: “the hope of it (that “it” again) survives,” “the facts of life unspoken.”

But, as with Boy George, Gregory is defiant. “Found guilty of no crime!” he sings more than once.

“But now the bank is broken” and all he has left is the last card, to turn down, in either sense.

And, in the middle there, somewhere:

“The best years of our lives.”

“They were the best years of our lives.”

I’ll turn the last card down rather than look at “modern romance.”

The record slips down the lift shaft.

The record slipped away, nearly unnoticed. It peaked at that most fatal of chart positions – number 41.

It told a story that nobody in the early autumn of 1982 wanted to hear.

That wasn’t how, or where, the story New Pop was supposed to go.

It was a “best kept secret.”

Yet the breakthrough would come. But would they still be who they once were?

Tight Fit

Who now knows whether or not the 12-inch of “Fantasy Island” was “actually better” than Led Zeppelin III? It’s out there, that 12-inch, in charity shops across the country, yours for next to nothing, and it is…different from Led Zeppelin III.

“Great group, Abba,” commented Peter Easton on BBC Radio Scotland’s Top

40 countdown show while fading out “Fantasy Island.” “Tight Fit seem to

think so, anyway.”

But “Fantasy Island”

was Tight Fit’s moment, in part a justification for New Pop being what,

in May 1982, it was – the boom-clap-boom-clap medley band, hitherto in

1982 the midpoint between “Sugar Baby Love” and “Wherever I Lay My Hat

(That’s My Home)” (Paul da Vinci sang the uncredited lead vocal, Paul

Young played the uncredited session guitar, and Tight Fit’s “The Lion

Sleeps Tonight” was not as good as Eno’s version), broke free, for

three-and-a-bit minutes, to record a song about Thatcher’s Britain and

involving water and scenery as a sort of metaphor. It was attractive and catchy, it blurred

lines between dream and reality (hey hey hey, suggesting that life

itself was the strangest dream of all), and it was produced by Tim

Friese-Greene, who six years later would produce, with Mark Hollis, Talk

Talk’s Spirit Of Eden, a record hugely influenced by the work of Roy Harper, after whom the final song on Led Zeppelin III was in part named. True love, holding everything together.

Dave Stewart and Barbara Gaskin

The Canterbury

School’s Secret History of Pop Music never quite picked up pace again

after “It’s My Party” just as Marty Wilde’s pop singing career never

quite picked up pace again after he got married; Adam Faith songwriter

Les Vandyke wrote “Johnny Rocco” – a Western fantasy, rather than a

spinoff from the 1958 American gangster B-movie starring a different

Russ Conway – for Wilde, and it stalled at #30 in the early spring of

1960. Stewart and Gaskin don’t really do anything too different to the

song, other than making its chord progression more, so to speak,

progressive, and emphasising the anti-macho root of the happy payoff, as

Gaskin sighs in pure Kentish tones: “Oi think foighting is pa-THE-TIC!”

A comment on the Falklands?

Toni Basil/Kid Creole and The Coconuts/Yazoo

Three number two hits in a row, and therefore three records to be written about more fully in TPL’s sister blog (in the fullness of time), so I will confine myself to the following observations, one on each:

- The dawn of the

video age; also the eclipse of the Chinnichap age, one last, fond hurrah

before being swallowed up by the future (Gwen Stefani, at this point,

is fourteen)?

- August Darnell; such class, such élan,

such persuasiveness does he use to make us believe in his cohorts’

backing vocals (“Ona! Ona! Onomatopoeia!,” “Break it gently to me

now!”), the busy percussion and the lazy trombone, all the better that

we don’t see the feral misanthropy at this song’s heart, worthy (if

“worthy” is the word) of Howlin’ Wolf at his most nihilistic?

- Yazoo, the old ways

kiss the new dawn, or is it a false dawn? “Wonder if you

understand/It’s just the touch of your hand” (low voice, confidential,

encouraging, fatal pause) “Behind a closed door” (the disappointment,

the ruptured rapture).

Lene Lovich

Quite the life Ms

Lovich has lived; born in Detroit of Serbian and American parentage,

moved to Hull as a teenager, involved in no end of alternative

happenings since the late sixties, wrote the lyrics to Cerrone’s

“Supernature,” was one of the “future Parliament” in the audience for

Chuck Berry’s “My Ding-A-Ling”…but “Lucky Number” was an NME number two so I’ll leave it to Lena to tell Lovich’s full story.

In the meantime,

“It’s You, Only You (Mein Schmerz)” – note the song’s strategic placing

right after “Only You” – just about got into our Top 75 (peaking at #68;

in the States it reached as high as #51). A cover of a 1979 Herman

Brood/Nina Hagen song, Lovich attacks the number with agreeable relish,

sounding remarkably like Patti Smith.

The Beat

It’s remarkable that

it has taken until now to get to the group some still call “The English

Beat,” at the point where they were practically finished. I’ve written

about I Just Can’t Stop It – one of 1980’s great party albums in a year of great party albums – before, didn’t think much of Wh’appen? and reckon Special Beat Service

somewhat underrated (my favourite of all Beat records might be the

12-inch of “Too Nice To Talk To”), including as it does the number one

which should have been, “Save It For Later,” and much purposeful

experimenting leading fairly directly to Fine Young Cannibals and

General Public alike. “I Confess” somehow manages to turn its implied

skank into a tabla-driven raga, while Dave Wakeling sings one of the

reddest-faced pop vocal performances: “I confess I've ruined three

lives/Now don't sleep so tight/Because I didn't care ‘til I found out

that one of them was mine.”

Toto Coelo

Toto Coelo were not

Bananarama. Toto Coelo were not The Belle Stars. Toto Coelo were not

Girls At Our Best. Toto Coelo were not The Au Pairs. Toto Coelo were not

The Slits. Toto Coelo were not The Raincoats. Toto Coelo were not

Pulsallama. Toto Coelo were not Raw Silk.

Toto Coelo were all-round family entertainers. Toto Coelo were Seaside Special. Toto Coelo were 1-2-3

with Ted Rogers and Dusty Bin. Toto Coelo were available. Toto Coelo

were reliables who always turned up, and on time. Toto Coelo were

showbiz troopers.

And “I Eat

Cannibals” really belonged in 1974. “I Eat Cannibals” makes better sense

in the bizarre 1974 world of its author and producer Barry Blue.

Bizarre? You haven’t heard “Pay At The Gate.” But in terms of “Miss Hit

And Run” and the extravagant “Hot Shot,” “I Eat Cannibals” made a

whole(some) lot more sense. In the bizarre 1982 world of New Pop “I Eat

Cannibals” looked and sounded like an insult to everything New Pop said

that it stood for. But “I Eat Cannibals” made number eight because that

was what people seemed to want. The waving of lusty hands and yippee-ing

amidst primary-coloured tinsel and small audiences pretending to be

happy.

Toto Coelo never had

another hit. The follow-up “Dracula’s Tango” is perhaps only remembered

by members of Toto Coelo. Toto Coelo were one-hit wonders. Toto Coelo

were not The Runaways.

Precious Little

This has to rank as the most obscure piece of music that Then Play Long

has unearthed. I do not remember “The On And On Song” coming out as a

single – and I didn’t miss very much back in 1982. I don’t recall it

ever being played on the radio, even though Radio 1 seemed desperately

dependent on “novelty” records as a distraction, and not necessarily

from New Pop. It was certainly never a hit. I don’t even remember it

“bubbling under.”

Did the single of

“The On And On Song” ever exist? Or was it only recorded in the hope

that it might fill a spare slot on a thirty-track double album “hits”

compilation? Why has the song apparently fallen through every black hole

that the pop universe has to offer?

I undertook some

detective work, and discovered that the single of “The On And On Song”

did indeed exist, and was mostly to be found, at the time, in 10p cutout

bins. It was recorded somewhere in Wandsworth, released on the

world-beating KA record label, and the B-side was an instrumental,

designed for singalong/proto-karaoke purposes. Or perhaps it was just a

quick and convenient way to fill up a B-side.

The song appears to

have been written and performed by one Trisha O’Keefe, of whom I have

been able to find no meaningful subsequent trace. All I do know is that

“The On And On Song” perhaps belongs on a compilation like the Bevis

Frond’s Music For Mentalists, alongside Rusty Goffe’s “I

Am The Music Man” or Reginald Bosanquet’s “Dance With Me.” It is a

cheery Cockney piano singalong – like Lynsey de Paul discovering Chas

and Dave – and lyrically something of a precedent to “Don’t Worry, Be

Happy.” Its basic piano/drum machine arrangement is augmented by effects

including a cracking whip, a children’s television choir which may well

be multiple speeded-up Trisha O’Keefes, a chorus of kazoos, Basil Brush

laughs, and octave-jumping piano vamps which are reminiscent of those

to be subsequently found in House and Rave music; indeed, these vamps

will be the effective lingua franca of the Top 40 a decade hence.

Trisha is feeling

daft because her bank manager won’t give her an overdraft to sail the

world in her homemade raft. It feels like a refugee from Milligan’s The Bed-Sitting Room,

and I briefly wondered whether this was a Crass-style socio-political

wind-up. But it was not, and so the song cheerily goes on and on and on

and on, this funny little song (one surefire way to ensure that a song

remains unfunny is to call it funny), because Britain goes on and on and

on and never really changes anything least of all themselves and in

truth never want change because they’re an island and they know what’s

what even if they become dependent on Red Cross parcels and all get

herded into the workhouse to service global lieges but it is Britain and

so let’s go on and on and on until the last star fizzles out and the

world turns orange as it melts and it goes on and on and ON

Whodini

Such a relief to

come across a song which sounds like the late 1982 “now” and perhaps

even the next century, let alone the current one. Whodini were three hip

hop guys from Brooklyn – in fact, were in on hip hop more or less from

the beginning – and “Magic’s Wand” was conceived as a tribute to WBLS

radio personality Mr Magic (on whose show the young Marley Marl served

as DJ) with considerable help from Thomas Dolby. Now Dolby’s agreeably

bending synthesiser lines, like PG Wodehouse shaking your hand in a

field of daffodils on Neptune, may sound as quaint as the Farfisa organ

on Johnny and the Hurricanes records, but the mood is good-natured and

as a low-calorie equivalent to “Buffalo Gals” (to which Dolby also

contributed) it makes one briefly nostalgic for times when “rap attack,”

“heart attack” and “Big Mac attack” meant nothing more than what they

said.

The Pale Fountains

The reaction was to

pretend that it was still the sixties. There was a lot of it about as

1982 crawled to what looked like being an anticlimactic end. In 1982

Radio 1 “celebrated” its fifteenth anniversary. On Thursday 30 September

their daytime shows played records from 1967 only. I was back at

university by then, and spent that day at home studying and writing up

this and that, and had Radio 1 on as background. It was an eerie

experience, hearing this fifteen-year-old time capsule of records which

already sounded as distant as Marie Lloyd and Billy Bennett, yet still

not of this world; 1967, like 1982, was a year in which pop exceeded

itself, decided to make of itself more than it probably was, and just

because bumptious ballads dominated the top end of the charts didn’t

cancel out all of the strangeness surrounding them. It

felt sinister, not quite right – I think pretty much every

non-MoR/novelty hit of the year got played at one point or another.

And as the autumn

skies steadily darkened, so that feeling must have slowly spread. “House

Of The Rising Sun” and “Hi Ho Silver Lining” returned to the charts

without any obvious precipitating factor. “Love Me Do” got its twentieth

anniversary “reissue,” finally made the top five and ensured that

history was rewritten in the winners’ favour. There were also sixties

pastiches, most of them feeble (e.g. “Danger Games” by the Pinkees, Mari

Wilson finally making the top ten with her worst single, where two

previous singles of genius had failed).

There were things

which forced themselves to stand out, like “Parade” by Roy White and

Steve Torch. Dismissed by most at the time as a pallid “tonight Matthew

we’re going to be the Walker Brothers” shadow of a record, I knew at the

time that this record was saying something more, was more urgent and

threatening (“I’m KILLING YOU!” went the throaty chorus). Steve Torch

was first choice as bassist for Dexy’s, but didn’t feel he was up to it

and passed on the offer, though did co-write several songs for the group

(notably “Liars A To E”) – hence the muttered, if mistaken, belief

among some listeners at the time who thought it was Kevin Rowland

singing. It remains a dark, twilight cloud of a record about sexual

jealousy and personal uncertainty, with dynamic chord changes, most of

which were carefully ironed out and simplified for Rhydian Roberts’ 2011

nice try at a cover version.

And then there were

Liverpool’s Pale Fountains. Signed to Virgin for a LOT of money, the

label needed a hit more or less straightaway. Hence, the big Fairchild

compressor orchestral balladry of “Thank You,” where a humble song (its

sentiments echoed by Michael Head’s disconcerting – in this fulsome

context - Edwyn Collins-ish vocal) is blown up out of its natural

proportions by strings, choirs, and Andy Diagram’s “Penny Lane” trumpet.

The record sounded exactly like what it was – scally indie made to wear

an uncomfortable tuxedo – and so stopped at #48.

They never got close

again, not even with 1983’s immensely superior follow-up “Palm Of My

Hand,” whose failure to chart I can directly ascribe to the fact that at

the time the single was bloody impossible to find. By the time they

belatedly reached their debut album, 1984’s Pacific Street, the group had moved on somewhat, and any potential audience remained baffled.

1985’s …From Across The Kitchen Table,

possibly an even better album, fell on largely deaf ears, and the band

split in 1987. Head then went on, via many well-documented troubles, to

form the group Shack, but it wasn’t until 1995 and the release of their

rescued debut album Waterpistol – then already four years old – that the critical tide began to turn his way. A second Shack album, HMS Fable, was also widely saluted, if hardly bought, but Head’s best and most intense work might be found on 1997’s The Magical World Of The Strands,

released under the banner of “Michael Head Introducing The Strands”

(they had lately backed Love’s Arthur Lee on his British tour); “Loaded

Man” in particular, an anything but funny or little song which goes on

and on and on, is not for the squeamish – an effort to make “the

sixties” matter again. And a word to Chris McCaffery, Head’s best friend

at school and bassist for the Pale Fountains, who died of a brain

tumour not long after the group split.

Shakin’ Stevens

“I don’t want to hear a lie”; strange how this truth-or-dare thing permeates Raiders.

There are the accordion and the castanets, the Latin tempo; if only

Shaky were David Hidalgo this could easily be Los Lobos. Nashville’s

Billy Livsey wrote the song; the ambience of a slightly claustrophobic

recording studio remains audible; and the single, the title track of a

top three album, peaked only at #11. It might have climbed higher if

Stevens hadn’t had to cancel a Top Of The Pops appearance; the vacant slot was given to the single at #38 that week – “Do You Really Want To Hurt Me?” by Culture Club.

Simple Minds

The Four Seasons of 1982 New Pop:

Winter going into spring: Pelican West.

Spring sliding into summer: Sulk.

Summer eliding into autumn: New Gold Dream.

Autumn moving into winter: A Kiss In The Dreamhouse.

1981 had seen Simple

Minds with hope. With Steve Hillage, a memory of the musicians’ days of

buying Virgin records out of the old Virgin Records shop on Argyle

Street, producing; with hope. With Jim Kerr, monologued by Morley in the

NME (it also appears in Ask), warning

that the old games won’t work anymore, telling critics not to do them

down and mark them like recalcitrant school pupils. The rocking old game

of talk them up one year, mark them down the next. Like Sons And Fascination was a bloody fourth year essay. An ink exercise partially crossed out with a red critical pen saying “See me.” But Sons And Fascination transcended all of that nonsense – to paraphrase Russell Brand said in The Guardian

just now, when music critics criticise musicians for using “long words”

and making “pretentious records,” they mean they’re using their long words, making the critics’ pretentious records – and the record (and its Sister)

spelled out hope. A hope in a record which appeared just after the

death of Bill Shankly and not long after the death of my father either. A

record which meant something extraordinarily special to the people who

knew, or lived in, or were leaving, the Glasgow of September 1981. An

overall patience, as opposed to the liberating, agonised rush of Empires And Dance.

You could listen to “Theme For Great Cities” and know exactly which

cities the Minds had in mind. Or to “The American” – the most exciting

final thirty seconds of any pop record, as Peel rightly said – or “Sweat

In Bullet” or “Seeing Out The Angel” and you knew you weren’t walking

alone.

New Gold Dream – and never forget its not-quite-subtitle, ’81-’82-’83-’84

(how thrillingly futuristic the notion of “’83” was in 1982, at least

the way Kerr exclaimed or proclaimed it) – represented pop’s better

afterlife, a quietly, modestly (or so it would appear; no less than

three drummers turn up in different places, and sometimes in the same

place, throughout the record) enveloped example of what we could have if

we admitted to ourselves that we wanted it. “Somebody Up There Likes

You” – remember that corner you turned nine years before and suddenly

the sun grinned away the grey overlay of cloud? A raised, beatific

eyebrow from somebody’s god? And yet, and especially throughout the

second half of the record’s second side, a realisation as resigned as

“Mr Blue Sky” that this can never last, that something darker and

perhaps more forbidding looms up: “The King Is White And In The Crowd” –

all build-up, no release, no rush; just waiting, waiting.

The hits –

“Miracle,” “Glittering,” Abba, we were fed up with not having a hit,

Peter Powell’s astonishing introduction on his Tuesday teatime chart

recap to the Minds making the charts at last; yes, these are our days,

Burchill’s nearly one-note but multichordal, silently screaming guitar

solo, the wider screen, the sheet-sweeping drums, Forbes’ midfield bass

suddenly buckling up like its knees had gone and then shooting into the

top corner when nobody was looking or expecting, “Prize” the Abba up to

the news heaven that many dared not dream.

And, above all, the song which opens the record.

And why Peter Walsh? He was a staff producer at Virgin, had worked on Penthouse And Pavement

and the group said fine. Then he worked with Peter Gabriel and China

Crisis and then Scott walked by and said, hey, can I have him for Climate Of Hunter and three tilting, drifting decades later he is still there.

But Scott walked by and asked Virgin for Peter Walsh because he had heard New Gold Dream and couldn’t believe what he was hearing. A dream for sure, unlike any pop record ever produced, not even that much like Abba.

“Someone Somewhere

In Summertime” seems to begin mid-song, or open up like a box of jewels.

As a song it feels as if it is being played on stilts forty thousand

feet high, removed from any easy notion of physicality. It ticks like

God’s clock pasted onto Jodrell Bank, all the better to time the stars.

It moves with one hundred and one orchestras of strings.

And all the time, Jim Kerr reaches out to his Bowie, from station to station:

“Stay, I’m burning slow.”

Walking in the rain, but it won’t last. Because moments burn, like gunfire.

The King is white and in the cloud.

He is returning from

somewhere, a journey unspecified. “Once more see city lights”; if he

sees a light flashing, does this mean that he’s not alone?

But “Brilliant days. Wake up on brilliant days.”

At the time, I could

think of nothing else except waking up on brilliant days, coming to

consciousness in a new and better world that was yours, only yours.

“Shadows of brilliant ways will change me all the time” – and something

happens which doesn’t happen often, if at all, in pop music; the

keyboards strike a Picardy third, minor-to-major, while bass continues

in its minor-key drone, Burchill’s guitar an uneasy yet completely

logical halfway house between the two.

And it builds up, as

such things build up – because it is already built up, far above us –

as Kerr sings: “Somewhere there is some place that one million eyes

can’t see/And somewhere there is someone who can see what I can see.” A

place for us as drums and bass pick up, church organ sounds out and the

rising bustle of “Eye Of The Tiger” is met far more satisfactorily. A

cry, a hope, no pain, only semi-bewildered joy.

And this was the lesson of New Gold Dream;

the shadows were leavening but New Pop couldn’t die or be killed or

supplanted; it proved itself endlessly able to twist into new turning

shapes, it would outlive all the racketeers who would profit in its

pseudo-wake. There was never going to be a wake for New Pop, travelling,

seeing out all angels, on a clear day seeing forever.

Robert Palmer

The song was written

by Jeff Fortgang about forty years ago. His attempt to break into the

songwriting business proved stillborn and he instead opted for a career

as a clinical psychologist. But the song didn’t die. People found it,

stumbled upon it. And sometimes altered it out of all recognition.

Including Robert

Palmer – now, Lena and I have been thinking very hard about who does and

doesn’t constitute New Pop, and we think that it should incorporate

those who had already been around for some time but didn’t find their

(im)proper selves until New Pop allowed them to do so. So Scarborough’s

Robert Palmer, rocking the pubs with The Alan Bown! and Vinegar Joe,

only really comes to life, or into view, when he asks Gary Numan for a

tune on his 1980 album Clues, and the record still sounds as bustling and foreboding as anything on early eighties Island Records.

And so his

“Some Guys Have All The Luck,” before Rod Stewart and Maxi Priest’s

boring textbook readings (though after Palmer died, Stewart began to use

his rearrangement onstage), where Palmer essentially cuts the song into

little pieces of white paper, throws them in the air, sees where they

land and sings what he sees. Which is mostly inarticulate grunts,

squeals, mutters and shrieks counteracted by an electrifying Russell

Mael falsetto. He happily, politely rebuts the concept of a pop song in

this pop song released and in the charts at the same time as “Poison

Arrow” and “Party Fears Two.” And he was loved and couldn’t be stopped

by anybody except him.

UB40

Wake up on less than

brilliant days? The rhythm squelches along electronically, as though

trudging through puddles to that bloody bus stop. The relationship of

bass to guitar and rhythm oddly parallels Simple Minds. Morose horns –

noticeably greyer than those on “Ghost Town” but perhaps UB40 recognised

the greyness more readily – bring down the clouds and help pave the way

for Roots Manuva (Run Come Save Me in particular feels

like an extended appendage to “So Here I Am” with some Dammers mischief

sprinkled). Even Brian Travers’ normally placid tenor sax is rather

angry, threatening to break into George Khan multiphonics at any time in

his solo.

But who in late 1982 was walking with UB40? Not too many people. Their first two albums, Signing Off (1980) and Present Arms (1981), both peaked at #2 (they both topped the equivalent NME

chart), and remain shockingly sober reflections on a world which didn’t

seem to rise much above the depths of Digbeth. Sober and patient; even

their stand-alone 1980 single “The Earth Dies Screaming” – so much

quieter, far more frightening than “Two Tribes” – scarcely raised its

voice. They found sober pride in their form of reggae (whereas Dammers

was itching to prove that the world wasn’t flat and Madness had moved

off to their own arena of matey darkness); it is like Bill Shankly’s

idea of reggae, and more and more people gradually drifted off.

So “So Here I Am,”

not quite their last 45 statement before 1983’s big turnaround, and Ali

Campbell is at the bus stop, wishing he were somewhere – and probably

somebody – else. There is no hope, not even the merest glimpse of

sunshine other than something mercilessly watery. The fadeout seems to

last forever as a final mockery of Those Fabulous Eighties.

Before UB40 reached back and became part of Those Fabulous Eighties.

Gregory Isaacs

A single of its

year, maybe of any year. No, it wasn’t a hit because it “sold in all the

wrong shops.” But everyone knew it anyway. Art Garfunkel. And Green

Gartside. These were the only two singers to come close to what the Cool

Ruler managed – deep emotion stated in a throwaway fashion, so

throwaway that it translates into the song of a choirboy.

“This heart is

broken in love,” purrs Isaacs over a steadily rocking electro-skank

pulse which hardly changes throughout the record. His “Tell her it’s a

patient called Gregory” outranks the entire career of Roger Moore

(indeed, he even conveys something of the prematurely

[s]exhausted-spirit of Sylvian on “Nightporter”). “Oh GOSH” – and then

comes the holiest of pauses – “oh the pain is getting worse”; and he has

never sounded more content. He sings “I’m hurt in love” deadpan –

melisma is entirely absent – and immediately you empathise with him as

you would do with the Green of “Simply Beautiful” or the Gaye of “If I

Should Die Tonight.” At that fadeout, another, conclusive, Gielgud-esque

“Oh GOSH…” beaming like a slowly awakening fire hydrant.

Oh yes, Robert Wyatt. There was always a fourth voice.

Morrissey-Mullen

“Let me tell you about my mother” – it could be a line from Fame,

couldn’t it? You will have probably long since guessed that despite the

many glimpses of hope on this particular transition, the story is fated

not to end well. I have said things about Blade Runner previously on TPL

and don’t propose to reiterate them here, except to say that Vangelis’

soundtrack must be listened to, making such startling use of old chart

ghosts (Peter Skellern, Mary Hopkin, Demis Roussos), and that its

saxophone solos are performed by Dick Morrissey.

The theme here is

the “Love Theme,” if it can so be called, and here is subjected to the

news-in-two-minutes mid-afternoon radio jazz-funk treatment. No stain on

the character of either the late Mr Morrissey, a hard bop tenorman who

had been a stalwart on the British jazz scene since the days of Ronnie

Scott and Tubby Hayes and who at much the same time as this performed

the saxophone solo on Orange Juice’s “Rip It Up,” nor of Glasgow jazz

guitarist Jim Mullen, but their interpretation is, to put it

diplomatically, uninvolving. But some of their backing musicians would

wash up, towards the end of the decade, within the menacing contours of

Chris Rea’s The Road To Hell – a record far closer to what Blade Runner implied.

The Kids From “Fame”

Like I said, it’s

the end of something, and this is the fulsome picture of the hell to

come; people pretending to be happy when their souls and their homes

have been stolen away, the school choir unity of too many charity

records to come, the desecration of gospel that will culminate in

Cowell, the central assembly point for people who don’t want subtext,

excitement or outrage – or even mild difference – but

shiny conveyor belt shite that will fit in the checkout with the Brillo

pads and Johnson’s air fresheners. Throughout 1983 it will be a repeated

story of what “we” might have had instead of what we have been left

with, and in at least one of these twenty-one cases the edict “he got

what he wanted but lost what he had” will have a singularly and

unpleasantly bitter aftertaste.

This music was no better when I was nineteen.