Marcello Carlin and Lena Friesen review every UK number one album so that you might want to hear it

Tuesday, 28 September 2010

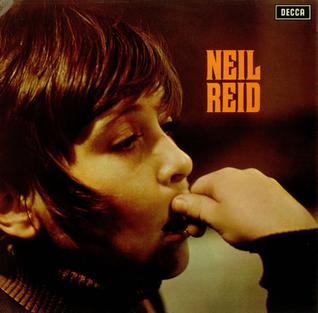

Neil REID: Neil Reid

(#105: 19 February 1972, 3 weeks)

Track listing: You’re The Cream In My Coffee/On The Sunny Side Of The Street/Peg O’ My Heart/Ye Banks And Braes/Happy Heart/When I’m Sixty Four/Look For The Silver Lining/If I Could Write A Song/When I Take My Sugar To Tea/My Mother’s Eyes/I’m Gonna Knock On Your Door/The Sweetheart Tree/One Little Word Called Love/How Small We Are, How Little We Know/Ten Guitars/Mother Of Mine

It’s an unusual cover photograph; he is not eagerly grinning at us, as you might expect from a performer of his age, but rather looking away from us, pensive, and with that pronounced upper lip, looking not unlike the younger Gordon Brown. The inevitable question is: what is he thinking? How did I end up here? Am I excited or scared? How long is this thing going to last? I wonder what my mother’s making for tea tonight. What is this West Hampstead, this big recording studio? How far away am I from home, exactly, and will I be able to find it again?

The Motherwell lad, sometimes billed as “Wee Neil Reid,” is still the youngest artist to top the British album chart, at 12 years and 9 months, but the child prodigy factor is only one element at work here. The record is the first augur of one of the key trends to dictate this tale in the future, namely success fuelled, and in many cases created, by the power of television. Throughout the seventies in particular, as we shall see, there were innumerable attempts to deny that this was the seventies, a craving to escape to any other time – the fifties, the sixties, nineteenth-century Vienna, even that abstract spider known as “the future” – than now, and music channelled through television helped to feed that hunger. A glance at the singles charts at the beginning of 1972 gives it away; as well as Neil Reid, we find Benny Hill, Cilla Black and Val Doonican, theme tunes from action series (The Persuaders - John Barry’s artful marriage of medieval cimbalom and future shock Moog remains unrivalled) and soap operas (“Sleepy Shores,” the theme from medical drama Owen M.D., starring Nigel Stock, the man who once pretended to be Number 6 – or was he the real One?), advertising jingles (“I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing”) and even a nod to the big screen (“Theme From Shaft”). Shortly thereafter, thanks to the dubious but unarguable power of Hughie Green’s Opportunity Knocks, Neil Reid’s debut album made it into this story. Why the sudden eruption? It should be remembered, amongst other things, that the period 1971-2 marked the point where colour televisions became affordable, when Grundig, Ferguson and others manufactured sets which anyone could buy.

But it should also be remembered that as 1972 dawned there were only three television channels – BBC1, BBC2 and ITV. The choice was less, external options were fewer, and so viewers had to tune in, essentially, to the same things. Thus audiences of 20-25 million for soaps and variety and comedy shows – then, almost half the population of Britain - were relatively commonplace. A common language was agreed and spoken. Shows such as Opportunity Knocks took full advantage of this; having moved to television from radio in 1966, the weekly you-the-people decide talent contest quickly caught on. Broadly similar in format to today’s Britain’s Got Talent, the avuncular Montreal-born Green presided over a bill of half a dozen or so acts, some singers and musicians, others comedians, yet others what were then known as “specialty acts” – magicians, jugglers, bodybuilders, plate spinners, even singing dogs – out of which viewers had to cast a postal vote on a weekly basis to determine which of these acts would return in the next episode. It was an enticing façade of popular democracy (“I mean that most sincerely, folks – it’s YOUR vote that counts!”) whereby the public could feel as though they were helping to make an ordinary person a star, but of course few of the acts who made it to the show were green, in any sense; nearly all of them had put in time on the club circuit, and Neil Reid was no exception.

The boy was apparently discovered singing at a Christmas party for pensioners in 1968, and over the next few years he appeared on various club bills during his school holidays. Eventually he came to the attention of the Opportunity Knocks producers, appeared on the show, and was a sensation; not since fellow Scotsman Jackie Dennis in the late fifties had a homegrown child star risen to such prominence, and that turned out to be a harbinger in itself (but more of that later). He was signed to Decca, the single (and featured song on the show) “Mother Of Mine” was rush-released at the end of 1971, and quickly climbed to number two (only prevented from topping the chart by the aforementioned Coke dynamo “I’d Like To Teach The World”). The local papers in Lanarkshire adored him, as did mothers and grandmothers everywhere.

An album of sixteen songs was put together by Dick Rowe (the man who a decade previously had turned down the Beatles; the fact that he was also the man who signed the Rolling Stones, the Moody Blues, the Small Faces, the Zombies, Van Morrison’s Them, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Tom Jones and Engelbert Humperdinck among others has been conveniently forgotten) and producer/arranger Ivor Raymonde, and unusually a degree of thought and modest adventure appears to have gone into its making. The songs were a mixture of old pre-war and inter-war favourites (for the grannies) and more contemporary material, and never is the selection or approach predictable, even if the approach doesn’t always work.

“You’re The Cream In My Coffee” begins with discrete ukulele and bass plucking, and what immediately strikes the listener is the unalloyed confidence of Neil’s voice – he occasionally misses his target in terms of phrasing and pitching, but the misses are always narrow and there is a latent power in his grain which somehow exceeds the material he’s been given to sing. He negotiates the tightrope trickery of the song’s complex middle eight, composed of successive trapdoors of modulations, very skilfully indeed. Unfortunately the intrusion of the teatime variety choir and vaudeville trombones rather spoils the track’s atmosphere, but the song soon cuts back to its original setting; there is something of a wink in Reid’s quick “You!” signoff.

The arrangement given to “On The Sunny Side Of The Street” is rather bewildering; the song is taken comparatively slowly, and the striptease mood (complete with nightclub bongos) strikes me as less than apt. Again the choir steals in to spoil things, and the North Pier organ solo midway through loads the track with excessive cheese, but the nice lyric change (“I’ll be as rich as Elvis Presley”) is carried off with good humour. Still, there is as yet nothing to suggest anything other than a fairly standard early seventies MoR album, and this feeling doesn’t radically change with “Peg O’ My Heart” – later used, in its original arrangement, as the theme for The Singing Detective - which here is treated in the manner of a Co-Op commercial. The song’s bridge is somewhat scrambled, and there is a bizarre interlude where the strings make a half-hearted attempt at a Highland reel (“Yip!” barks Neil) – wait a minute; is there something else going on here?

His version of the traditional Scots song “Ye Braes And Banks,” however, is a different matter. Raymonde’s arrangement becomes liquid and iridescent, and there is something in the tone of Neil’s voice which now suggests possible futures; the song is taken patiently and rather opaquely, but there are long stretches where, even as a Scot, it is impossible to discern exactly what he is singing – instead, there is an almost alien purity about his voice as an instrument in itself, and I have to remind myself that, not only was Elizabeth Frazer about a year Neil’s senior, but also Ivor Raymonde’s son Simon would eventually become a Cocteau Twin; I wonder if the two boys ever met, and what influences from this Simon would carry over with him a dozen or so years hence. Again, with “Happy Heart,” Neil is stretching out his vowels and consonants in a way I’ve only known one other singer to do – his near contemporary in Dundee, Billy MacKenzie. Now he is really settling into the record, and even essays a bit of scat singing with some success. His “When I’m Sixty Four” involves a children’s choir (and, if the photographs on the rear of the album are anything to go by, Neil himself at the piano); it’s a pleasant little conceit, a knowing in-joke.

But “Look For The Silver Lining,” a Jerome Kern ballad from 1919, provides the record’s most heartstopping moment, and Raymonde’s most creative production and arrangement work; Neil’s voice is pitched as a distant echo, not quite graspable...and then the song, quite unexpectedly, goes “out”; cymbals fade into processed hisses, there are meandering meadows of guitars electric and acoustic (and one of the guitarists is, to cloud matters further, Derek Bailey, not a million miles from his other-galaxy work on Tony Oxley’s “Stone Garden”), rumbling bass and tinkling electric piano, and then the song fades out of focus and even audibility, eventually returning on a crest of Free Design harmonies (“Look for the silver lining, silver lining”); the atmosphere is somewhere between early Boards of Canada, Belbury Poly and Saint Etienne’s “Avenue.” The track not only cries out to be sampled, but also works as a portrait of genuine hauntology; that is, the piece is haunted by the ghosts of the music which will, intentionally or not, follow it. Side one then winds to its agreeable end with Howard Greenfield and Neil Sedaka’s “If I Could Write A Song,” and Neil’s general phrasing here is highly reminiscent of that other former child star, Scott Walker.

“Take My Sugar To Tea” conceptually balances out “Cream In My Coffee” and is similarly arranged, with more ukulele and the occasional blast of trombone (possibly from Paul Rutherford – I am not sure how this album is affected by having two-thirds of Iskra 1903 playing on it), but the arrangement is rather stilted and bumpy (the generous tympani solos do not help) and Neil again sounds a little out of his element. Then again, towards the song’s end, ukulele, electric guitar and tympani engage in a three-way summit of pointillism which hovers delicately atop the border of abstraction. “My Mother’s Eyes” is more successful; Raymonde remembers his Dusty Springfield and Walker Brothers days and lets out the Spector floods in his orchestration (complete with echoing pianos, etc.). Once more, the choir is strictly not needed, but the approach by both arranger and singer is epic, stentorian, rhetorical, and Neil works up to a satisfyingly chilly high note finish.

“I’m Gonna Knock On Your Door,” however, is tackled as neither Eddie Hodges or Little Jimmy Osmond could have imagined it; fuzz guitar and furious Hammond organ lead us, via some handclaps, into a netherworld somewhere between “Hang On Sloopy” and the not-yet-recorded “Children Of The Revolution”; the approach is defiantly bump and grind (but he’s only twelve!) and amidst the thunderstorms of rhythm and descending (into hell?) organ riffs, Neil sounds a bit lost.

However, we then move into a meditative state-of-the-world interlude. “The Sweetheart Tree,” composed by Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer, was commissioned for Blake Edwards’ movie The Great Race; when I was eight or nine, I thought the latter my favourite film, uproariously funny, and I haven’t revisited it since for fear of disappointment (since it was another in the long post-Around The World In Eighty Days/It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World series of throwing lots of famous names together and making them have hilarious scrapes in all sorts of different places; I suspect that I would now be bored rigid by Lemmon’s hamming, by Natalie Wood’s blankness, by the overlong Prisoner Of Zenda skit which climaxes the film). It’s an odd choice for a slapstick comedy, but note the guitar (and/or clavichord) work here which gives the number an ethereality which, again, would find its true home with Robin Guthrie and (via Neil’s admirably controlled vocal) Elizabeth Frazer; one almost forgets the return of the kids’ choir. “One Little World Called Love” leads us back to the main 1971-2 milieu, that of where the world is going, that love could still save us all, although note the deadpan guitar comping throughout, and also the occasional breakout of a disturbing shard of lyric (“A peal of thunder when God sounds his gun”). This sequence concludes with the plaintive waltz (but composed by the radical composer Earl Wilson Jr, although this version seems to take its cue from Josef Locke’s 1969 reading) “How Small We Are,” bookended by an astutely solemn brass chorale.

“Ten Guitars” is the Humperdinck standard, and both Neil and Raymonde do their best to make it sound as unlike Engelbert as possible. Flute flutters, drums are busy in a hip-shaking way, but the message persists (“Through the eyes of love, you’ll see a thousand stars”), even as Reid manfully (or boyfully) takes the song out with some exhortations (“Come on everybody!,” “All together now!”).

“Mother Of Mine” itself is left until last. Composed by the guitarist Bill Parkinson (formerly of Screaming Lord Sutch’s backing band the Savages, and an unwitting contributor to the key song on entry #109), the song’s simple poignancy works in its favour and Neil’s performance is faultless, even through the lush choirs and final key change. But there remains something oddly otherworldly about it; it doesn’t really fit into any timespan (is it 1952 or 2022?), and he is singing such lines as “When I was young” when he is still only twelve. And there is, of course, something which moves me about the record which maybe exceeds the record itself; listening to Neil’s singing here (especially his five-note “way”s), I cannot help but think of the fourteen-year-old Billy – a man who would eventually end his own life out of unreachable grief for his mother’s death – and how, or if, he would have sung this; the similarities are unavoidable. And that's not even to mention the record's role as a bookend of premature maternal lament for its decade, the other being Lydon's beyond-articulation howls of grief on "Death Disco."

But Neil’s life continued to a much more successful issue. His initial success was not sustained – a follow-up single, “That’s What I Want To Be,” and follow-up album, Smile, both released later in 1972, both barely scraped into their respective Top 50s. Of course, the Osmonds had arrived in the interim, and suddenly they seemed much hipper, much more in tune with the times; the final irony came when Little Jimmy covered “Mother Of Mine” for the B-side of his Christmas chart-topper “Long Haired Lover From Liverpool.” Neil couldn’t have competed with that, and nor, I suspect, would he have wished to do so. He returned to the clubs for a further year or so and then his voice broke. He continued to record for a time, including with Roy Wood – notably his more than decent 1974 single “Hazel Eyes” – but to little avail, and he moved into the touring musical circuit for a few years before opting out of the music business altogether. Eventually he became a practising Christian, and today he lives happily in Blackpool, works as a management consultant and runs what he calls a progressive, 21st century church named Oasis Blackpool. His initial success did open the floodgates for a host of wannabe child stars, most (but by no means all) of whom similarly came up via the Opportunity Knocks route. Of that flock only Ricky Wilde (as co-producer, co-writer and guitarist for his younger sister Kim) and Bonnie Langford have continued to prosper; other stories are necessarily more tragic or routine. I doubt that there will be much, if any, call for Neil Reid to be upgraded to CD status, but as a modest stew of differing time periods in popular music it does what it set out to achieve, and the astonishing “Look For The Silver Lining” in particular demands rediscovery.

Tuesday, 21 September 2010

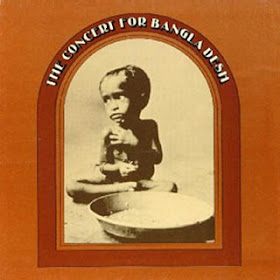

VARIOUS ARTISTS: The Concert For Bangla Desh

(#104: 29 January 1972, 1 week)

Track listing: George Harrison – Ravi Shankar Introduction/Bangla Dhun/Wah-Wah/My Sweet Lord/Awaiting On You All/That’s The Way God Planned It/It Don’t Come Easy/Beware Of Darkness/While My Guitar Gently Weeps/Medley: Jumpin’ Jack Flash-Youngblood/Here Comes The Sun/A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall/It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry/Blowin’ In The Wind/Mr Tambourine Man/Just Like A Woman/Something/Bangla Desh

Although Bolan cried, “It’s a rip-off!,” some sixties survivors evidently felt the need to prove that rock music needn’t be a rip-off. In 1980 John Lennon opined, apropos the Concert for Bangladesh and the controversy regarding the whereabouts of the eight million dollars that the concerts and associated records and film had raised, “But it’s all a rip-off.” Then again, George Harrison had invited Lennon to participate, provided that Yoko didn’t, but an argument between John and Yoko took place and Lennon pulled out.

However, if the 105 or so minutes of the triple box set prove anything, it’s that they stand as a marker of rock’s attempt to grow up, to prove that, as had been promised in the sixties, this music could make a difference to the world, and in particular to the lives of people who had nothing to do with rock. Bangladesh had been born, painfully, out of the ashes of East Pakistan, but West Pakistan, under the iron rule of Yahya Khan, did not wish to relinquish its control over the country; there had already been a disastrous cyclone in 1970, but in March 1971, refusing to acknowledge the results of the democratic Bangladeshi election three months previously, Khan sent his troops into the country and undertook Operation Searchlight, a genocide programme comparable to that which would be unleashed by Pol Pot in Camodia four years later. The original album sleevenote refers to a million Bengalis murdered, although subsequent statistics have put that figure up to three million; this led to the beginning of the Bangladesh Liberation War. In addition, ten million Bengalis fled the country, seeking refuge in neighbouring India, and were susceptible to cholera and other diseases, not to mention the continued threat of monsoons.

The concerts had been the original idea of Ravi Shankar; himself a Bengali, and horrified by the massacres, he wanted to put on an event to raise both funds and awareness, and asked his friend George Harrison for advice with the hope that he might be willing to produce the concerts, if not participate in them. He gave Harrison extensive literature and newspaper cuttings concerning the history and then-current state of Bangladesh; similarly horrified, Harrison immediately offered to take part and get as many other musicians as possible to do so. Liaising with Allen Klein, the final line-up was agreed in some 4-5 weeks; as Harrison comments on the album, many of his colleagues had cancelled other gigs or commitments in order to participate. One, Eric Clapton, was in the middle of his heroin phase, and only turned up for rehearsals the day before the concerts. For Harrison himself, this would be his first stage appearance since the break-up of the Beatles, and – the ultimate coup – Bob Dylan agreed to take part, marking his first gig since the 1969 Isle of Wight set.

The organisation took place on the turn of a dime – as did the quick writing and recording of Harrison’s fundraising “Bangla Desh” single – and two concerts were given on 1 August 1971, one at noon and the other at seven in the evening; the album collects the best performances from both. As a feat of management, the event was something of a miracle; as a listening experience, it raises some peculiar issues.

The album begins with Harrison wandering onstage to a wall of whoops and cheers from the audience; he asks them to “settle down” for Shankar’s opening set, attempting to convey to them the complexity of Indian music (“a little bit more serious than our music”), and then Shankar comes on. He too asks for patience and open-mindedness from the audience, and also requests silence and non-smoking. Evidently both men were being cautious, and Shankar takes pains to explain that “your favourite stars” will appear in the concert’s second half and that this is the music, the culture, of the nation for whom they are here to raise funds; to understand the cause, one must understand the culture. The four musicians – Shankar on sitar, Ali Akbar Khan on sarod, Alla Rakha on tabla and Kamala Chakravarty on tamboura – tune up for around a minute and a half, only to be met by a round of applause. Shankar smiles and indulges the audience before launching into the two-part “Bangla Dhun,” a pair of improvisations based on a Bangladesh folk tune. A relatively light run for these masters, the piece is divided into a dadra sequence (six beats) and a teental sequence (sixteen beats). In the meditative first half, Shankar and Khan intertwine beautifully, Khan’s sliding quarter-tones in particular reminding us how this music had so beguiled and entranced the likes of Coltrane a decade earlier; there are of course reminders of the other musics which this music would go on to influence, including both English and Scottish folk music, country and bluegrass, and (of course) psychedelic rock – in the teental section, the patiently escalating dazzle of the four musicians’ interactions (plaintive sitar, flowing sarod, dramatic tabla-tamboura call and response sequences) is enough to send one into hypnosis; as the music speeds faster and faster, psychedelia suddenly seems the plaything of children – and it is all based on a subtly rephrased (with every recurrence) four-note sequence. As with Dylan’s later set, this seems a league above everything else that would go on that day, and the audience’s thunderous reception proves that they were ready.

Harrison then returns to the stage, running through some All Things Must Pass material; “Wah-Wah” benefits from Leon Russell’s piano swipes, “My Sweet Lord” is done as though from the lounge, with some rather sour guitar commentary from Clapton, “Awaiting On You All” turns on the almost inaudible axis of Billy Preston’s organ. But, despite the phalanx of musicians onstage (including all four members of Badfinger, inaudibly strumming away on acoustic guitars), the original album’s sound wall isn’t quite recaptured, and moreover – and particularly halfway through “Awaiting” – the feeling comes through that we are at church, attending to a sermon. A long way away from the rabid rave-ups of Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, Harrison is keen to remind his audience that they are there for a Specific Reason. The retrospective listener, however, feels as though he is being lectured to, and hence the protestations of both Harrison and Shankar that they deal in music and that politics have nothing to do with why they’re there are, charitably stated, disingenuous; if rock is supposed to change the world, shouldn’t it be taking a less fence-friendly stand?

Billy Preston gets his solo spot, and his “That’s The Way God Planned It” wipes the floor with the 1969 studio version; his idea of gospel is more florid and lively than Harrison’s, with fine call and responses with the multiple backing singers, a storming organ solo from Preston himself, and a real holy roller of a crescendo with doubling tempi and ecstatic tambourine. But Ringo then sings his hit “It Don’t Come Easy” and gets the second biggest round of applause of the day; even though he fluffs his words in the final chorus, the audience forgives and blesses him. The original single has much of the offhand joie de vivre about faith which Harrison wasn’t quite ready to unleash, and although his strained voice takes a firm second place to his and Jim Keltner’s drumming, he seems to be the concert’s most welcomed presence.

Harrison takes over again for a couple more songs; the gloomy “Beware Of Darkness” bears some extra light thanks to Leon Russell’s agreeably gruff co-lead vocal and Liberace piano, while following extended band introductions by Harrison (Ringo is acknowledged by a quick gallop through “Yellow Submarine”), Clapton – still wanting to be “Derek,” just another guy in the band – has his moment in “When My Guitar Gently Weeps,” his and Harrison’s guitars sobbing at each other, even if the backing is a little over-emphatic, a tad too pub-rock (amazingly, it was only at this point that most people realised that Clapton had played on the original recording).

Then comes the album’s unexpected highlight, Leon Russell’s solo spot. The least known of the featured musicians, and therefore probably the one with the most to gain in terms of reputation, he tucks into the Stones and Coasters with such volcanic force and ribald humour that he makes me want to re-evaluate his entire back catalogue; finally, here is the spark, the duende for which the concert has been crying out. “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” was a brave one to essay in this context, and the most astonishing thing about it is perhaps Russell’s vocal – with his repeated, ragged “WHOOO!” screams, he sounds like, of all people, Iggy Pop; and Don Preston’s guitar and Carl Radle’s bass respond with a deadpan thwack straight out of “TV Eye.” Halfway through, Russell modulates into an extended improvisation on the Coasters’ “Youngblood,” framing the song with long out-of-tempo half-scat half-rants about faithlessness and childishness, eventually dovetailing back immaculately (he’s been cheating, sneaks back in the early hours, his baby wonders what he’s been doing but after a considered pause decides that it’s ALLLLLL-RIIIIIIIGGGGGHHHTTTTT) into “Flash,” and then back towards a Merrie Melodies “Youngblood” signoff. Chaotic, rambling, rash – Russell pretty well steals the show, wraps it up and takes it under his arm to the pawnbroker’s.

Harrison comes back on, with Pete Ham of Badfinger in acoustic tow, and runs through a briskly-taken and rather superficial take on “Here Comes The Sun,” even if the twin acoustics’ interplay immediately recalls Shankar and Khan (it is a real shame that Badfinger didn’t get a set of their own; still the most undervalued pop group, power or otherwise, of the seventies, especially by those who ripped them off and drove half of them to suicide; their story makes that of their oddly logical twin Big Star appear like a walk in the park in comparison).

But then Harrison asks us to welcome “a friend of us all – Bob Dylan,” and the audience goes apeshit. Much horsetrading between Apple and Columbia was required to ensure Dylan’s presence on the record (and indeed the 1991 2CD version on which I am basing this piece appeared on Columbia/Sony) but it was more than worth it; the pictures alone indicate that this was something other than what had previously been going on, and Dylan wisely opts to stick to the folk; his is a deceptively understated and nonchalant set, and all five songs have a relevance, however indirect (from “Just Like A Woman”: “I was dying there of thirst”), to what was actually happening in Bangladesh (earlier on in the show, the audience clapped along to Harrison’s “Bangla Desh” record as it played under documentary footage of atrocities – did they really only come to see lots of famous people on the same stage together, with the cause trailing a very distant second?); “A Hard Rain” is treated almost playfully, the lines coming at almost random divisions (though the scratch band assembled for Dylan’s set – Harrison on electric, Russell on bass, Ringo on sturdy blisters-on-fingers tambourine – do a fine job of second guessing the great man), but the song is never treated as a throwaway. “It Takes A Lot To Laugh…” dices with death, ownership and commitment but here it’s Dylan’s pivotal “BOSS,” un-resolving into a spreading helter-skelter of ululations, which commands the song’s regretful flow. “Blowin’ In The Wind” is treated with careful solemnity but that too is almost completely overwhelmed by an unexpectedly passionate vocal – my God, he still CARES about this at this late stage – from Dylan, an octave above his normal range, stretching like James Carr, howling like Pickett. On this night it could scarcely have sounded less relevant. This “Tambourine” teems with pain, almost losing itself before Russell’s walking 4/4 bass strolls with us back to reality. “Just Like A Woman” is taken at a funereal 4/4 pace; at first it sounds as though Dylan is taking the piss out of Jagger (this “she begs” is gnarled up to sound like “she BAKES”), but then the hurt steals into his timbre, and that last extraordinary “guuurrrlllll” he holds like an unstable Colt .45, turns it into a Shepp wobble, then a terrifying growl, hurling its shards, its atoms, into Harrison’s guitar (the only live version to beat it is the one Bridget St John did, somewhere in the middle of England, in late 2007, where she sings it quietly, from the perspective of the woman – and you are numbed, truly shocked; now, she quietly hisses, you think you know about pain?).

There’s no real way to follow that, but Harrison has to come back on and finish the concert somehow; his “Something” is somewhat gruff and the attendant irony of Clapton’s querulous slides need not be over-underlined. Still, it rocks up to an entirely inapposite finale, and then the cheers and the inevitable wait for the encore. Amazingly, “Bangla Desh” the song is a tougher little cookie than I had remembered; the words still sound as though tossed together in twenty seconds (which was probably not far from the truth) but Spector’s production (and he is on the unobtrusive mix for this set) takes full advantage of the wrong-footing chord changes and there is a cloud of numbed rage which somehow lifts it out of the bob-a-job league. Here Harrison gives his most ferocious – and life-filled – performance on the record, with everyone – Jim Horn’s tenor, Clapton’s anguished, breaking-out-of-himself guitar solos – elevating towards a double tempo rampage, as though failure to resolve things in Bangladesh could drag the rest of the world down with it. After that, there is really nowhere else to go.

And, for the all-star benefit concert, there were surprisingly few other places for it to go throughout the seventies; unlike Live Aid, etc., this was an integrated group of famous people on stage pretty much throughout the whole event, rather than a slideshow of famous people doing their individual turns. Perhaps those nasty, inconvenient politics might have had something to do with it, but there is also the fact that the proceeds from the event, in all its manifestations, languished in limbo for several years due to the simple omission by its producers to apply for tax-exempt status. It does seem that the money eventually did get through; it wasn’t nearly enough to make any practical difference, but awareness was raised, and Bangladesh struggled slowly and painfully towards a full democracy in the early nineties. I myself was pleased to come across my copy in a branch of Oxfam, since the money raised from my purchase will go – with any luck – towards relieving the current flooding crises in Pakistan. But if rock wanted to grow up, it seems to me that it had to acknowledge things like politics as well as accidents of nature, and it’s possible that the only such events which still attract mass audiences and funds are those which strive to be as apolitical as possible. It’s not until the turn of the eighties, with the likes of Secret Policeman’s Ball, the Concerts for the People of Kampuchea and No Nukes, that the crossover all-star fundraisers began to pick up real steam. Still, as fumbling and messy as their approach was, Shankar and Harrison were ahead of their time, and ripping anyone or anything off was, I’d wager, the last thing on either of their minds.

Tuesday, 14 September 2010

T. REX: Electric Warrior

(#103: 18 December 1971, 6 weeks; 5 February 1972, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Mambo Sun/Cosmic Dancer/Jeepster/Monolith/Lean Woman Blues/Get It On/Planet Queen/Girl/The Motivator/Life’s A Gas/Rip Off

(Special thanks to the indefatigable David Belbin for kindly sending me a CD-R of this album’s second CD issue, and to the Camden branch of Music & Video Exchange for supplying me with an original LP edition, complete with the crucial inner sleeve and label designs)

The first question has to be: why the title? What are they – or, more accurately, he, or, even more accurately, s/he – fighting against? The cover, as with the record itself, is quite unlike any other number one album of this year, indeed seems diametrically opposed to all the rest of them, even though Hipgnosis designed it; the elf almost dwarfed by his amps, thrashing away at his guitar, bathed in a halo of deliberate gold. The future beckoning us with unplaceable lips and radical pixie boots. This is a new kind of electricity, and the war is being waged against certain things which have come before it, or were standing in its way.

Electric Warrior marks the point – more so than the soundalike compilations – where the British album chart caught up with pop. It provides a definitive and cocksure ending to a decidedly unsure year, while also unmasking the road shortly to be followed. However, it doesn’t quite shake its head at all of the past; in presumably purposeful contrast to the futuristic black and gold of the cover, the inner sleeve presents us with misty, pastoral, angels-in-their-hair sketches of Marc Bolan and Mickey Finn, as though it were still 1967 and the countryside; meanwhile, on one of the labels (the one not occupied by Fly Records’ sixties calligraphy), the duo appear in a field, ready to be snapped for Fabulous 208, or Look-In, or any of the teen magazines ready to take them, and Bolan in particular. Yet the record drips with words uncommon; “doth,” “perchance,” “whence” and “stars in my beard” (the latter a deliberate, door-closing reference to the Tyrannosaurus Rex days), as well as Bolan’s hair and hips, suggest a spirit whom Keats would have understood instantly. An old Romantic ready to embark on a true New Romanticism, a full decade before that term was to be traduced by some of the children and teenagers who listened to and devoured Electric Warrior (other wiser ones would subsequently remember him as the fulcrum of what would come to be known as New Pop) – but the cloudy pastoralism is balanced out, almost flattened, by the Jaguars and Cadillacs which rear and roar their carburettors throughout the record; look, Romantics, at how all the world has changed!

Of all the artists featured in TPL 1971, Bolan seemed to have the greatest urge to free himself from the sixties (although he was of course one of its most integral components); he didn’t possess autumnal regret or tints of rose for times spent and chances missed – on the contrary, he was the keenest to get on with “now,” to drag the rusty body of sixties rock and pop into something which would look like a future to those who didn’t need or want to remember the sixties (as with the teen audience who made up the broadest base of T. Rex’s fan demographic).

Certainly of all the albums featured in TPL 1971, Electric Warrior is the most sheerly playable; as with all great pop albums, one requires to play it repeatedly, in partially stunned disbelief that this is actually happening (or did happen almost forty years ago) – its swing is easy, its come-ons bursting with come. Bolan’s was a more youthful take on sex and rock than, say, Zeppelin – it is easy to forget that in fact Bolan was almost one year Plant’s senior – and one more acutely programmed to what the hips, the nascent stimuli, in his fans desired. His is a more aqueous seduction, slower, more persuasive, and ultimately far more comprehensive.

But where did that voice of his come from? “Mambo Sun” opens the record – and as a record, Warrior’s success is largely down to the studio ingenuity of producer Tony Visconti (together with his team of engineers, including future key figures such as Malcolm Cecil, Roy Thomas Baker and Martin Rushent) – with what is essentially a breakbeat; percussion, electric guitar, ‘cellos, violins and, finally, Bolan’s voice all enter separately and combine in connected universes. What is immediately remarkable is the use of space and patience – here, space is the pace. But that voice! Was there any real precedent for it? There are some clues in “Mambo Sun”; the song begins like a Kevin Ayers wet dream (“Beneath the bebop moon/I wanna croon with you”) but Bolan’s Received Pronunciation vowels conjure up the spirit of one of the original New Pop forebears, Noel Coward, even as his corn-stirring vibrato reminds us (and some in 1971 needed to be reminded) of Buddy Holly. But this is far from a straightforward seduction; he is trying to get to us (“My life’s a shadowless horse/If I can’t get across to you”), wanting to manufacture his own oceans, even referencing Marvel Comics (“On a mountain range/I’m Dr Strange for you,” with a rhetorical chord augmentation). The pining turns to panting (“Upon a savage lake,” “My wig’s all pooped for you”), and eventually Bolan breaks out of the poetry, draws a careless breath and cries “TAKE ME!” – and no one could resist or refuse as he turns on the tantric scat lantern, full of “ow!”s, “uh-uh!”s and “baby”s, Visconti’s strings rising up wistfully at the end in the manner of prototype synthesisers.

And there was also, lest we forget, Syd Barrett, who could so easily have dreamed up half the songs on the album, particularly the regenerating reincarnation cycle of “Cosmic Dancer,” wherein, ahead of acoustic guitar and lowering strings, Bolan patiently, but very unplainly, dances from womb to tomb and back again, apparently free of gravity and care (“I was dancing when I was AAAHH!”). Is twelve too late, is eight too early. There is a trace of disturbance in his “wrong to understand,” as he asks us to recognise “the fear that dwells inside a man…OHHH!” Visconti’s strings alternate between barbed wire swipes and Mantovani soothers. “Here I go again, once more…” he sings, preparing yet again to be reborn, and his “OW OWWW!” heralds a three-way dialogue between backwards guitar (that 1967 river again), backing vocals and drums, eventually resolving in trading of fours between Bolan and Bill Legend – the latter’s work is exemplary throughout the album. He can live forever if he so desires, but can he ever negate the past, least of all his own?

“Jeepster” solves that problem by joyfully lining up three decades of pop tactics and jumbling them all up into one of the greatest of all pop come-ons. Released as an unofficial single at the end of 1971, it was kept off the Christmas number one slot only by Benny Hill’s novelty hit “Ernie,” but the milkman’s strawberry yoghurts couldn’t hope to produce nearly as much cream as Bolan generates here. Immediately the stony (or Stones-y) backbeat is offset and lightened by Finn’s congas – the double-drum approach inevitably leading to thoughts of Glitterbeat and, eventually, Antmusic – and although the song is based on a mongrelisation of Howlin’ Wolf (“You’ll Be Mine”) and Roy Orbison (“You’re My Baby”), it sounds nothing like either. We are in the land of the blues but this is a different, if related, urge to that of the Wolf or Muddy, not the least because the song is repeatedly slung into a minor key by Visconti’s “I Am The Walrus” ‘cellos in each chorus. Meanwhile, Bolan merrily mixes psychedelic abstraction (“You’ve got the universe reclining in your hair”) with upfront fuck-me-nowisms (“I’ll call you Jaguar/If I may be so bold”), although he eventually hardly requires the words to spell out his intent. His gasp before the percussion/guitar break (complete with Slade-anticipating boot-stomping and sandpaper handclaps), his climactic “OWWW!,” his “Uh, uh, UHH!!”s – did Michael Jackson or Prince ever get to listen to his work at the time? Or maybe they all got the same notion from different perspectives of James Brown. Either way, note how Bolan’s guitar steadily ups the sexual ante – it’s hardly present in the early part of the song, but pours all over the latter half, and how “upon your frozen cheeks” eventually explodes into vampirism – “I’m gonna SSSSSSUCK YA!” Bolan grins, twisting the key consonant just enough to make it suggest an “F” rather than an “S” (although Greil Marcus may yet be alone in hearing “One-two-three-FUCK!” in the intro to “I Saw Her Standing There”), and abruptly one wonders why the rest of 1971 pop couldn’t harbour this kind of sensual good humour. The song thrashes orgiastically towards fadeout.

Darker clouds decorate the halls of “Monolith”; there’s a hi-hat hiss, then a guitar snarl, then – suddenly – a stately ballad, Bolan’s treated guitar striding in and out of its woods – and what is it about? Amidst all the “kingly”s and “whence”s Bolan delivers a warning that this cannot last forever: “And dressed as you are girl/In your fashions of fate/Baby it’s too late.” Part Dylan, part “Out Of Time,” part Zappa satire, even (“Lost like a lion/In the canyons of smoke – girl it’s no joke”). Flo and Eddie’s backing vocals and Visconti’s strings sound haunted; handclaps stutter out a messy ending. Don’t start creating new gods this early in the new age.

And then Bolan does Elvis, hilariously and splenetically (that “One an’ two an’ BUCKLE MAH SHOE!” intro); “Lean Woman Blues” is a great mash-up which imagines Presley kidnapped by Ken Kesey to participate in The Basement Tapes. The song is a trainee cobra bluesy crawl, slightly redolent of Zeppelin, although here Bolan is both gorged by a knife and compares himself to “a child in the sand on the beach of the land of you.” Multiple Marc guitars move out of tonality and rhythm towards the song’s end; shit, guys, when does this peyote wear off?

“Get It On” priaptically opens side two. It was their only American hit, and even there it had to be retitled, with quite magnificent meaninglessness (or anti-meaning) "Bang A Gong." But magnificent it is; the song is Bolan’s fullest realisation of a carnal pop-rock synthesis which demands (or requests) elegance rather than crude groin-thrusting. The groin does thrust and throb all the way through the song, but with so much righteous style; the 45-degree bend between the snare drum and the downward piano roll (played by an uncredited Rick Wakeman) which introduces each verse; the superb interaction between strings and baritone sax (at the record's end there's a lovely little unison line between violin and Ian McDonald’s alto and baritone saxes), the second set of drums which slink just a quarter of a beat behind the main set.

Unlike the hapless, hopeless likes of Mungo Jerry, Bolan makes sex sound sexy. I thought for several decades he was singing "cat in black, don't look back and I love you" but actually it's "clad in black." No matter; the entire song is full of these sublime hiccups of irrationality - "You got the teeth of the hydra upon you," "You've got a cloak full of eagles," "You gotta hubcap diamond star halo." Well, what words can frame deliriously wild love? "You've got the blues in your shoes and your stockings," could have come straight out of Gene Vincent, who died that year; in a not-at-all odd way, Bolan makes him live again. Not to mention the wonderful Brideshead Revisited "a"s of his pronunciations of "dance" and "chance,” or the fulsome, genuinely androgynous backing vocals of Flo and Eddie.

With this song one knew that Bolan owned 1971 and he knew it; no one else that year seems to have had the confidence to assert themselves kindly on the public by announcing "You're dirty sweet and you're my girl" other than in odious, previously noted macho ways (1971 was also the year of "She's A Lady," penned by Paul Anka and gruffed ignobly by our old friend Tom Jones; you can prod the padlocks of his zip and his distressed lady's mouth). And, at fadeout, he gives it all away; a slurred reference to Chuck Berry’s “Little Queenie” and it all becomes clear; the staccato, spacious rhythms derive from Eddie Cochran, the nonchalant self-confidence from Berry himself (“Jeepster” is also a souped-up and slightly slowed-down “Maybelline”); this is rock ‘n’ roll reborn, retooled and flashing hydras of punctum everywhere it shone.

“Planet Queen,” meanwhile, could have strolled out of the Elysian fields of four summers past, particularly the sky-cracking ascending choruses (“Love is what you want/Flying saucer take me away”), although Flo and Eddie, late of the Turtles (with their own subtly undermining take on the pop song – “Elenore” for instance deconstructing itself as it goes on, and don’t underestimate the Chinese Opera strings of “You Showed Me” - still fresh in discerning minds) give their best performance on the record; as Charles Shaar Murray commented at the time, who else but members of the Mothers of Invention could deliver the line “Give me your daughter” straight-faced and mean it? In addition the “flying saucer” collides with the “Cadillac King”; the song moves up an octave for its final verse with yearning, practically starving strings, and finally Bolan cannot help but hiccup, breathe and sigh his immense sigh of cosmic relief at the song’s end.

“Girl” likewise could have come from the Tyrannosaurus songbook; a relatively straightforward acoustic ballad (at least until Bolan’s electric starts randomly cutting in) in which the singer surveys God, Boy and Girl and finds them all wanting, in different ways (“Mentally weak,” “You’re mentally dying,” “Come and be real for us” – indeed, Bolan’s electric hisses up towards fury at the climactic “OH GOD!”), although the lovely double-tracked flügelhorn improvisations of Burt Collins provide a Milesian cushion of comfort.

“The Motivator” proceeds much along the same lines as “Get It On,” albeit with a Syd Barrett remix; it bangs against currents of tambourine-driven stomp and perilous descending-string minor modulations, the orchestration highlighting the battle between the song’s two halves; on one hand, he loves fashion – no previous TPL entry has made such a fetish out of clothes – but is aware of its deadly limitations. “I love the velvet hat/You know, the one that caused a revolution” – in other words, the one Marie-Antoinette used to wear; and then there is the King’s broken crown, the golden cat in the bedroom – where does it all end (“I love the clothes you wear/They’re so mean, they’re so fine”)? The repeated descents of “Love the way you walk,” etc. appear to demand a question mark, but Bolan eventually settles for an appreciative “Walk on!” Steve Currie’s bass provides its own dubious, inventive commentary. Bolan’s guitar erupts like a coil spring (in the song’s climactic refrain), bookended by two different guitar solos, one minor and modal, the other engaged in a debate with Visconti’s pizzicato strings. Eventually a Moog and string unison take the song to its uncertain finish.

“Life’s A Gas” is the album’s simplest, shortest and most moving song, and as regretful but realistic a farewell to the sixties as Lennon’s “God.” Bolan muses about what could have been (“I could have chained your heart to a star,” “I could have built a house on the ocean,” “I could have turned you into a priestess”) but realises that dreams are just those, and what counts is the reality: “But it really doesn’t matter at all (cymbal hiss) – life’s a gas!” with that gulp which may signal either release or grief, the retrospective poignancy of Bolan’s “I hope it’s gonna last” notwithstanding. As was the message of Vaughan Williams’ Tallis Fantasia, celebrate what we are as human beings, and be happy with that…

…because if we’re not (and the agitated guitar and string figures at the end of “Life’s A Gas” give us fair warning) we get “Rip Off,” the album’s completely unexpected climax wherein Bolan upturns all our notions about T. Rex and throws them into a cauldron of shock. An autodestruct button of spleen? It starts with a breakbeat – and then Bolan raps, in an ugly, monstrous roar of a voice, over Ian McDonald’s greasy saxes. He grunts, he moans, tearing down every effigy of the past, as well as some of the present, including his own (“Terraplane Tommy wants to bang your gong it’s a RIP OFF!! Such a RIP OFF!!”). Again, more indebted to the Lennon of “Walrus” than it might wish to admit, this performance seems to subvert everything we have heard on the record, thrashing like a beaten turtle between keys C, F, G and A, between exultation and despair, nude dancing dudes or moon with a spoon – it’s all fake, you’ve been had. “Ooh my GOODNESS baby!!” Bolan squeals as the song boils over – and McDonald, formerly of King Crimson and then a member of Keith Tippett’s Centipede, breaks over a C major string drone for a free alto sax cadenza (compare with his work on the second half of side three of Centipede’s Septober Energy). Guitar feedback bubbles into the picture but both strings and McDonald then unexpectedly resolve into a troubled, extended E major – the “Day In The Life” chord, hanging there like a glittering sword; do you dare to touch it?

Yes, there was the precedent of Donovan and the singles Mickie Most and John Cameron produced for him in the folkie-discovers-sexy stakes, but as with The Queen Is Dead, Electric Warrior casts such a shadow over the peers of its time that one briefly wonders why anyone else wanted to make records. Like the Smiths’ masterpiece, it sums up its time, places pointers to a better future. On the cover Bolan looks as though he is radiating rock. His beats are slippery and deceptive, breathe along with him. The relationship of voice to string section was the best since Astral Weeks. And yes, Oscar Wilde, with that damned underworld dandyism, and the Sebastian Horsley to come – and everybody else who got turned on in 1971, at the right or sometimes the wrong age (he sings so much about clothes!), to whom Bolan was, more or less, the new Beatles, who wanted to create a future as glamorous as his promised to be – and never let the Mod factor be forgotten; Bolan was a very early heavy hit on the London Mod scene, even as a model – but think of that slow bubbling up and turnaround at the end of “Rip Off” (how many other futures did he invent with that one track? Roxy Music? Heavy metal? David Bowie – who was making similar, if subtler, moves with Hunky Dory at the time, although that record didn’t break big until post-Ziggy stardom; “The Bewley Brothers” plays like the saddest flipside “Rip Off” could ever have; but hell, doesn’t this invent Ziggy? Turning kids onto John Coltrane? Or, on a wider level, at least allowing Green Gartside or Neil Tennant to think about how they should sing, if at all?), and think of Jason Bourne rising out of that river at the end of The Bourne Ultimatum; he’s given birth to something that can’t be killed, and the glam steps to follow were built by his uniquely carnal baptism.